A complicated case of scabies in a health care provider

Received: 31-Dec-2017 Accepted Date: Feb 12, 2018; Published: 19-Feb-2018

Citation: Lukambagire AH, Kini LC, Daudi M, et al. Complicated case of scabies in a health care provider. J Skin. 2018;2(1):7-10.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Scabies is a highly contagious, neglected cutaneous parasitic disease, associated with poor individual, community, environmental circumstances and health. Hospital acquired scabies may occur due to contact between patients and healthcare providers. The non-classic presentation of scabies presents a challenging case to the clinician.

Case presentation: A male healthcare provider presented with a dry, itchy rash on his lower legs which was non-responsive to initial chemotherapy, developing complicated hypersensitivity symptoms. Later skin biopsy and scrapings yielded Sarcoptes mites.

Management: During the first 2 weeks, the patient was dewormed at a health centre and later given intramuscular, oral and topical antihistamines a referral hospital with little improvement. A final dose of ivermectin cleared the rash and itching.

Conclusion: WE present a case of nosocomial atypical scabies in a healthcare worker which posed a rare challenge. A complicated clinical history and previous medications appear to have masked the classic features.

Keywords

Scabies; Atypical; Healthca; Nosocomial

Scabies is a parasitic dermatosis with a worldwide distribution. It is an itchy skin condition caused by the hypersensitivity reaction to products released by the microscopic mite Sarcoptes scabei. A number of various mite species are associated with the infestation of animal (mange) and human (scab) hosts, the dust or itch mites, comprising various species of Sarcoptes and Demodex, are most commonly associated with human scabies [1]. Scabies was added to the World Health Organization (WHO) list of neglected tropical diseases in 2013. According to various studies, scabies due to the itch and dust mites affects up to 300 million people annually worldwide and may cause large nosocomial outbreaks with considerable morbidity among patients and healthcare workers [2].

The clinical presentation includes pruritus and a variety of dermatological lesions ranging from papules, pustules, burrows, nodules, and wheals [3]. In epidermal parasitic diseases (EPD), host-parasite interactions are restricted to the stratum corneum, the upper layer of the epidermis, where the ectoparasites complete their life-cycle, in part or entirely. Lesions are commonly found on the wrists, finger webs, antecubital fossae, axillae, areolae, periumbilical region, lower abdomen, genitals, and buttocks. Diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination, and demonstration of mites, eggs or scybala on microscopic examination [4].

The incubation period for scabies is about four to six weeks. The itch leads to frequent scratching, which may predispose the skin to secondary infections. In its early stages, scabies may be mistaken for other skin conditions. Secondary bacterial skin infection, such as impetigo, are common complications [5-7]. Close skin contacts such as family members and sexual partners are the commonly mentioned modes of transmission. Spread of scabies to health care workers attending infected persons is rarely mentioned in the literature [8,9]. The clinical presentation of the initial dermatologic condition varies significantly with the host’s level of hygiene. The classic burrowing rash and inter-digital pustules are a common finding in persons with poor hygiene standards or as with Norwegian scabies, lowered immune status [10-12].

Diagnoses are based on clinical history or risk and physical signs. Histopathology examination of skin biopsies remains the clinical gold standard [4,13,14]. Other diagnostic tests include skin scrapings, dermatoscopic, intradermal skin tests, antigen-antibody detection and PCRbased diagnostics [15-18]. Treatment options include both topical and oral therapy; topical permethrin combined with ivermectin has shown efficacy in small group studies [19]; topical treatments include 5% permethrin cream, 1% lindane (gamma benzene hexachloride) lotion, 6% precipitated sulfur in petrolatum, crotamiton, malathion, allethrin spray, and benzyl benzoate [6]. Prevention strategies ranging from quarantine [20], light and humidity modifiers [21] as well as mass drug administration [22-24] to endemic populations regardless of clinical presentation. Simple education on improvement of personal and community hygiene have all been tried, tested and proven effective [25].

Case Presentation

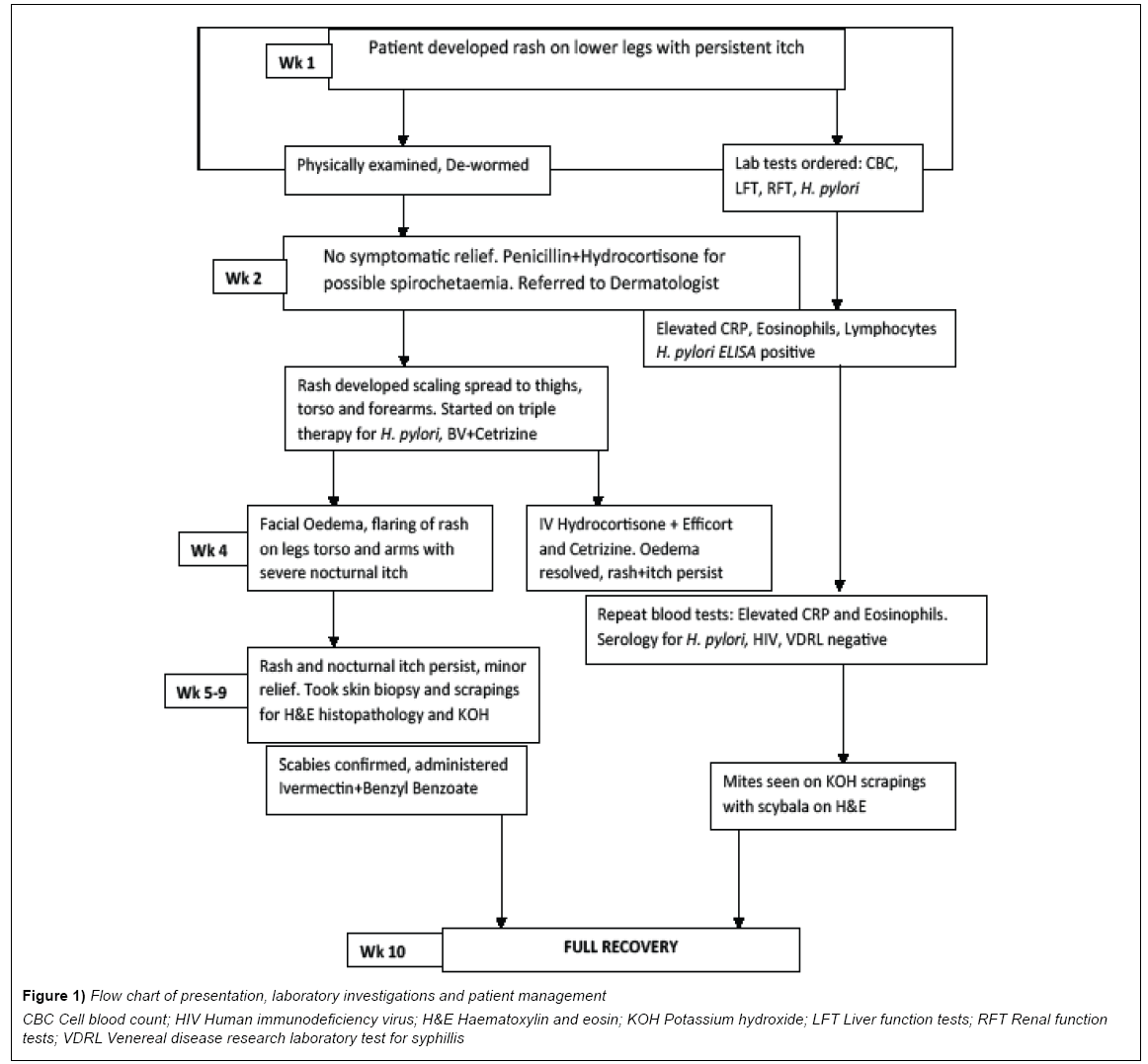

A 34 year old, male healthcare provider presented at the referral dermatology clinic of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre with persistent rash on his lower legs that was itchy especially at night (Figure 1). The initial dry rash was neither tunneling nor suppurative (Figures 2A and 2B). The symptoms had been persistent for the past two weeks despite several applications of oral anti-histamines and topical steroids. The patient also received antihelminthes (Albendazole) treatment for possible intestinal worm infection, without relief. He reported a history of peptic ulcer disease and his memory of exposure to an infested patient was unreliable. After a preliminary period of 5 weeks, he developed angioedema and a patchy erythematous rash and his family medical history was noncontributory.

Figure 1: Flow chart of presentation, laboratory investigations and patient management

CBC Cell blood count; HIV Human immunodeficiency virus; H&E Haematoxylin and eosin; KOH Potassium hydroxide; LFT Liver function tests; RFT Renal function

tests; VDRL Venereal disease research laboratory test for syphillis

Diagnosis

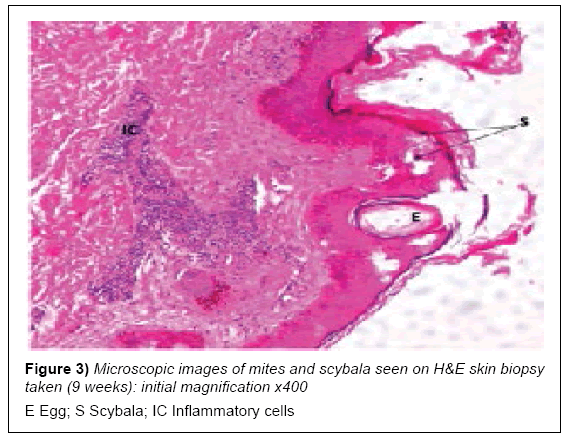

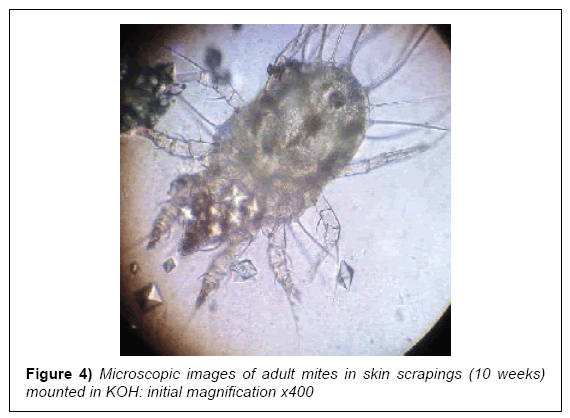

At early presentation a full heamogram and serology tests for liver and renal function were done after a cursory physical examination. The rash was restricted to his lower legs and unremarkable, while the heamogram was normal for red blood cell (RBC) indices but showed mild lymphocytosis with an acute eosinophilia. The liver and renal function tests were normal with an elevated acute phase reactant, C-reactive protein (CRP). Serology and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) for H. pylori were positive (Table 1; pre-intervention). A skin biopsy was taken from his right upper forearm for histopathology examination and later skin scrapings from some late expressing interdigital papules. These both revealed scabies mites and scybala on examination (Figures 3 and 4).

| Test | Findings | Normal Range | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary (2 weeks) | Post Intervention (4weeks) | |||

| Haemogram RBC (Total) Haemoglobin |

4.2*1012/L 14.8 g/dL |

5.3*1012/L 15.3 g/dL |

3.8-5.8*1012/L 11.5-16.5 g/dL |

Normal Normal |

| WBC (Total) Lymphocytes Eosinophiles |

8.25*109/L 4.1*109/L (42.5%) 4.9*109/L (18.2%) |

10.23 *109/L 2.6*109/L (31.7%) 2.8*109/L (14.3%) |

4.0-12.0*109/L 1.0-4.0*109/L 0.0-0.5 *109/L |

Normal *Lymphocytosis **Eosinophilia |

| Serology AST/SGOT ALT/SGPT Total Bilirubin Direct Bilirubin Creatinine Urea Uric Acid Glucose (Fasting) C-Reactive Protein H. pylori ELISA |

40.9 IU/L 38.5 IU/L 20.5 IU/L 4.2 IU/L 52.5 µmol/L 4.2 mmol/L 0.4 mmol/L 4.5 mmol/L 68.5 mg/L 0.854 COI |

41.2 IU/L 35.5 IU/L 23.4 IU/L 4.0 IU/L 56.2 µmol/L 4.3 mmol/L 0.38 mmol/L 4.2 mmol/L 24.3 mg/L 0.103 COI |

<46 IU/L <50 IU/L 2-26 IU/L 1-7 IU/L 44-88 µmol/L 2.5-8.9 mmol/L 0.24-0.47 mmol/L 3.5-5.5 mmol/L <8.0 mg/L 0.263 Cut-Off |

Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Borderline Normal **Very High *Positive |

*The mild lymphocytosis and elevated H. pylori antigen ELISA resolved during the intervention period (4 weeks)

**The marked eosinophilia and raised acute phase reactant sustained throughout the treatment period well into the three months of follow up

AST/SGOT Aspartate aminotransferase or serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase; ALT/SGPT Alanine aminotransferase or serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; COI

Cut off index; IU International units; mmol Milimoles; μmol Micromoles; L Litre

Table 1: Summary of major haematology and serology results pre- (2 weeks) and post intervention (after 4 weeks)

Results and Management

During the first 7 days of symptom presentation, the patient was de-wormed with 400 mg Albendazole for 3 days. As this provided no relief, he was referred to the dermatology clinic a week later, where based on his initial laboratory results, he was administered Benzyl Penicillin 2.4 mg IM stat, 0.0127% topical Hydrocortisone and a 10 day course of 10 mg oral Cetrizine. Two weeks later, he developed angioedema, which responded to 100 mg IM Hydrocortisone Succinate stat and topical Betamethazone Valerate (BV) 0.1%. He was also started on triple therapy for H. pylori infection (250 mg Azithromycin, 40 mg Pantoprazole and 250 mg Amoxycilin for 2 weeks) and advised to clean out his clothing and beddings. Finally, during the 10th week, he was administered a single dose of oral Ivermectin at 200 mcg/Kg, followed by topical Benzyl Benzoate which appeared to clear the rash and alleviate the persistent itch.

Discussion

Scabies remains a neglected tropical disease of poverty despite the large number of cases reported per year, and the millions more at risk in tropical countries. The definitive diagnosis of a typical early case of scabies is usually a result of high index of suspicion during clinical examination, with a support of microscopic examination of skin biopsies or scrapings [14,18]. Both clinical skills and diagnostic tools are rarely available at primary health care levels resulting in institutional outbreaks of scabies. It is estimated that by the time a case is positively identified, no less than 3 healthcare workers in a typical tertiary health centre have been sufficiently exposed for effective transmission of mites [6,9,20]. This factor alone makes the effective control of scabies particularly difficult [4,13,26,27]. Although nosocomial scabies is perceived to be of rare occurrence, a high-risk index and history of exposure are leading indicators of suspicion, while the typical dermatological pattern with a persistent nocturnal itch justify a confirmatory examination [14,17]. Where scabies presents atypically, it is often challenging to definitively diagnose a case based on the early symptoms [14,28].

This patient presented at least two weeks after onset of symptoms, which typically occur 4-6 weeks after exposure. The initial pattern and presentation of the rash was atypical, compounded by an unreliable recall of contact risk and a history of gastric ulcers. Recent studies have also established associations between bacterial infection and either local and/or diffuse skin manifestations with increased exposure to gastro-intestinal tract antigens as they circulate through the blood stream [10,29]. Considering this patient’s history and non-specific presentation, peptic ulcer disease was indeed the primary suspicion. The initial management targeted towards a possible H. pylori infection however led to a more acute onset and spread of the initial rash with development of angioedema.

In cases involving single exposure of a healthy individual with sufficient personal hygiene, the infesting dose of mites may survive and reproduce for up to 45 days before presenting symptoms abate [4,26]. The patient was seronegative for any immune-compromising diseases and had no history thereof. Although the skin scrapings and biopsy eventually showed the presence of sarcoptes mites and scybala in the stratum corneum, this was a rather late discovery. The classical interdigital pustules appeared towards the end of the 9th week, after the patient had been started on oral ivermectin. Preliminary laboratory tests remained insufficient for a conclusive early diagnosis [14,17].

The recommended management of oral ivermectin at 200 mcg/Kg body weight, followed a week later by topical benzyl benzoate appear to have provided symptomatic relief after almost 3 months and numerous intervention attempts. The cost in time, resources and various interventions during this period are no doubt significant and address a key concern associated with NTDs [6,14,18]. The preventative measure of cleaning out his wardrobe and beddings plus housing may have provided crucial disruption of a self-re-infection cycle [6,11-13]. Although the eventual responsive treatment supported by the microscopy findings strongly suggest a case of scabies, the preliminary diagnosis of dermatosis due to peptic ulcer disease was equally supported by a positive ELISA as well as a sustained elevation of serum CRP and marked eosinophilia.

Conclusion

This case proved particularly challenging and confirmatory diagnosis was only achieved towards convalescence. It is enlightening as a possible differential for healthcare workers with atypical presentation of nosocomial scabies. A complicated case presentation may have masked the clinical picture and delayed early suspicion and management of scabies.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case study and any accompanying images.

Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- Paasch U, Haustein UF. Management of endemic outbreaks of scabies with allethrin, permethrin and ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 2000:39.

- Barberi S, Ciprandi G, Verduci E, et al. Effect of high-dose sublingual immunotherapy on respiratory infections in children allergic to house dust mite. Asia Pac Allergy. 2015:5.

- Panahi Y, Poursaleh Z, Goldust M. The efficacy of topical and oral ivermectin in the treatment of human scabies. Yunes. 2015:61.

- Kim HS, Kang SH, Won S, et al. Immunoglobulin E to allergen components of house dust mite in Korean children with allergic disease. Asia Pac Allergy. 2012:2.

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J. Epidermal parasitic skin diseases: A neglected category of poverty-associated plagues. Bull World Heal Organ. 2009:87.

- Feldmeier H. Treatment of parasitic skin diseases with dimeticones a new family of compounds with a purely physical mode of action. Trop Med Health. 2014;4:215-20.

- Scheinfeld N. Controlling scabies in institutional settings: A review of medications, treatment models and implementation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:31-7.

- Hadfield-Law L. Scratching the itch: management of scabies in A&E. Accid Emerg Nurs. Elsevier. 2000:8.

- Bouvresse S, Chosidow O. Scabies in healthcare settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010; 23.

- Vorou R, Remoudaki HD, Maltezou HC. Nosocomial scabies. J Hosp Infect. Elsevier. 2007:65.

- Costa JB, Rocha de Sousa VLL, da Trindade Neto PB, et al. Norwegian scabies mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Ann Bras Dermatol. 2012:87.

- Clavagnier I Dealing with scabies in a hospital ward Rev l’infirmière. 2015:64.

- Khan A, O’Grady S, Muller MP. Rapid control of a scabies outbreak at a tertiary care hospital without ward closure. Am J Infect Control. 2012:40.

- FitzGerald D, Grainger RJ, Reid A. Interventions for preventing the spread of infestation in close contacts of people with scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD009943.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20.

- Angelone-alasaad S, Min AM, Pasquetti M, et al. Universal conventional and real-time PCR diagnosis tools for Sarcoptes scabiei. Parasites & Vectors. 2015:1-7.

- Stroehlein AJ, Young ND, Korhonen PK, et al. The Haemonchus contortus kinome - A resource for fundamental molecular investigations and drug discovery. Parasites & Vectors. 2015:1-13.

- Arlian LG, Feldmeier H, Morgan MS. The potential for a blood test for scabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015:1-11.

- Currie BJ. Scabies and global control of neglected tropical diseases. N Engl J Med. 2015:373.

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic Disea. J N Engl Med. 2015:373.

- Haag ML, Brozena SJ, Fenske NA. Attack of the scabies: What to do when an outbreak occurs. Geriatrics. 1993:48.

- Manuyakorn W. Assessing the efficacy of a novel temperature and humidity control machine to minimize house dust mite allergen exposure and clinical symptoms in allergic rhinitis children sensitized to dust mites: A pilot study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2015:129-35.

- Alipour H, Goldust M. The efficacy of oral ivermectin vs. sulfur 10% ointment for the treatment of scabies. Ann Parasitol. 2015;61:79-84.

- Paasch U, Haustein UF. Management of endemic outbreaks of scabies with allethrin, permethrin and ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 2000:39.

- Mohammed KA, Deb RM, Stanton MC, et al. Soil transmitted helminths and scabies in Zanzibar, Tanzania following mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis - A rapid assessment methodology to assess impact. Parasites & Vectors. 2012:5.

- Wong LC, Amega B, Connors C, et al. Outcome of an interventional program for scabies in an indigenous community. Med J Aust. 2001:175.

- Elgueta NA, Parada EY, Guzmán GW, et al. An outbreak of scabies in a tertiary-care hospital from a crusted scabies case. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2007:24.

- Kabululu ML, Ngowi HA, Kimera SI et al. Risk factors for prevalence of pig parasitoses in Mbeya region, Tanzania. Vet Parasitol. 2015;212:460-4

- Wang, IJ, Tung TH, Tang CS et al. Allergens, air pollutants, and childhood allergic diseases. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219:66-71.