A discussion on patient care, information, communication, and social media influencing bias

Received: 15-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5634; Editor assigned: 18-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. PULJNRP-22-5634(PQ); Accepted Date: Nov 28, 2022; Reviewed: 22-Nov-2022 QC No. PULJNRP-22-5634(Q); Revised: 27-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5634(R); Published: 30-Nov-2022, DOI: DOI: 10.37532/ Puljnrp .22.6(10). 169-171

Citation: Paul S. A discussion on patient care, information, communication, and social media influencing bias. J Nurs Res Pract. 2022; 6(10):169-171.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Today's culture is rife with misinformation and deception, which gained popularity largely as a result of the growth of social Media. The most crucial component of care delivery, management, and evaluation has long been acknowledged to be Effective communication between those providing care and those receiving it. This essay will investigate communication through the perception of information created as a result of personal influencer selection and attempt to ascertain how such influences on patient care.

Key Words:

Influencers, Social media, Misinformation; Patient Communication

Opinion

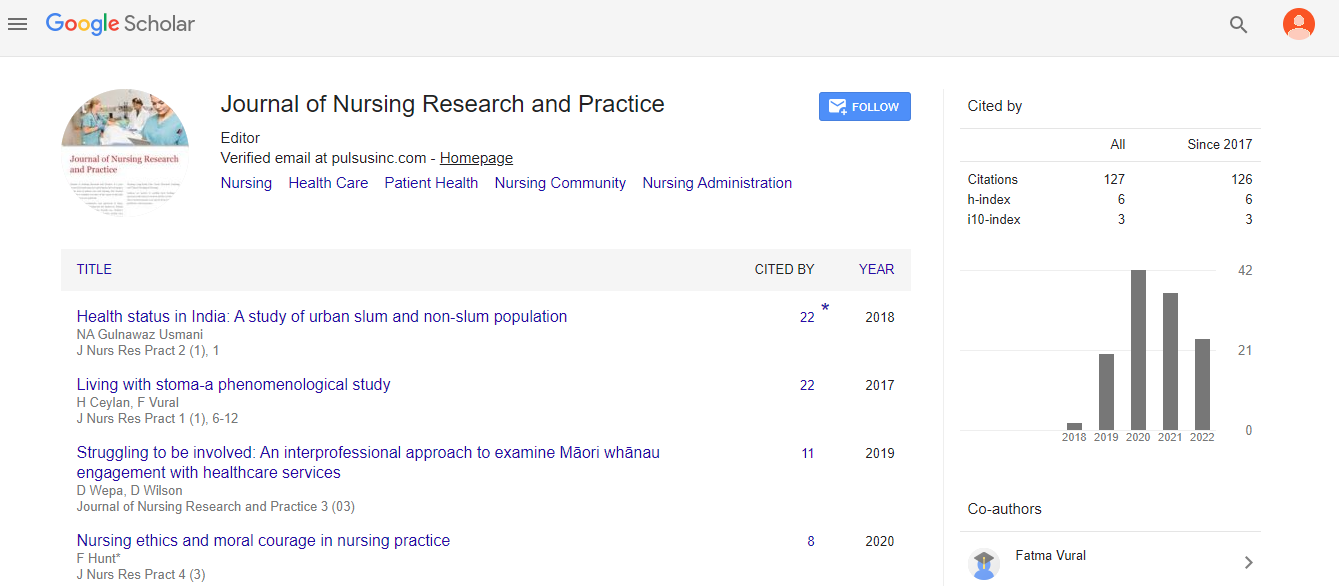

Today's culture is rife with misinformation and deception, which gained popularity largely as a result of the growth of social media. Disinformation is a subset of misinformation that is purposefully false and meant to mislead or confuse people. Misinformation is generally considered to present false information, presented as fact, regardless of intent to deceive. They add special complexities to health and social care, affecting both the patient or consumer and the care provider. In health and care settings, it is acknowledged that interpersonal communication is the most crucial link between those providing, managing, and assessing care for patients and those providing that care healthcare professionals. The coronavirus pandemic has brought to light the importance that each of us attaches to communication, which can take the forms of verbal, non-verbal, and Para-verbal exchanges. In order to understand how such communication affects patient care, this paper will examine how the perception of true or false information is formed following the personal selection of influencers through digital media, along with developed bias. Human communication is sometimes thought of as the exchange of information between two or more people during live discussions that take place in person, over the phone or via video, or through written correspondence like letters. Today, communication may involve the use of digital devices, enabling a variety of communication applications including information searching, group meetings, e.g. Zoom, We Chat, Whatsapp, Instagram, TikTok, and following the most recent remarks, e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Sina Weibo, News agencies. The main question being investigated in this paper is whether the variety of information sources that are available has the potential to cause bias in people, and in particular, whether this has the potential to affect how nurses and other healthcare professionals can help those under their care by remaining objective when speaking with patients. We are aware of the need of providing unbiased care to individuals we treat thanks to standards set by regulatory bodies for health professionals, but in an era of digital influencers, how can bias be lessened to fulfill patient needs in practise? It is generally agreed that most people entering adulthood have a significant history of life events, and that each person's history is unique. As the days, weeks, months, and years pass, more decisions will need to be made regarding the paths each person decides to take and whether biased ideas are a problem to living and learning. A great deal of personal history has been shaped by individuals around them. In recent years, it seems that the abundance of information made available to us through various online platforms has caused many people to be picky about the influences they choose to follow. According to Chaffey, social media users are now multi-networking across an average of eight social networks and messaging applications, spending 2 hours and 24 minutes every day. Everyone is aware that almost everything we do online is being tracked in some manner, and that privacy rules have lagged in protecting us from feeding the big data machine. We are aware that after making an online purchase, we will probably encounter advertisements for related products on other digital platforms. We have just recently come to understand this. However, have we begun to consider how we utilize smart technologies in our homes and how our decisions now about the use of technology like virtual assistants, smart fridges, smart televisions, and so on, will affect our decision-making tomorrow? The pandemic in 2020 amply illustrated the necessity for agility and resilience in our daily lives as patients or health professionals, or both. Of course, it is not a one-direction issue; there will be many benefits as well as challenges in the way we live as we advance further into the 21st Century. Consider a humanistic information model as a representation of information "flows" of individuals, be they those in our care as patients or those in our care as colleagues or family, in order to further explore the issues and frame the theme of the paper. The four gears should be viewed as turning even though they are depicted as static on the page since turning cogs produce power. The four cogs can stand in for an individual, a team, a department, a professional discipline, or an organization, but for the purposes of this discussion, we'll focus on the version intended for individual use. We constantly receive information through all of our senses when awake. The acquisition gear drives the other cogs, and frequently, this information is presented to us with predetermined values jagged line. That is, from sources that place value on the information, like newscasts and conversations with friends; or, from sources that are bland straight line and have no values added, like, for instance, a certain aroma from a candle, though this may evoke memories within us. Information can flow from the acquisition cog to the processing cog and the dissemination cog, where it is either processed or promptly discarded. The processing cog is the vital link between newly acquired knowledge and previously stored data, the latter of which holds our life history, including the choices we have made throughout our lives that have shaped who we are today. There is a movable line that separates conscious from unconscious thought within the processing cog. Because we have learned how things work throughout our lives, like doors, we frequently pass through doorways without giving it any thought. If we are blocked, on the other hand, the thought level crosses into conscious mind, and we read pull as we were pushing the door. In health and care settings, the line for a professional member of the care team may be quite high unconscious level, almost automatic, as a result, a conversation with a patient has already been carried out, whereas for the patient all the information has the potential to be new to them. The position of the line determines how much conscious or unconscious thought we place upon new information, and the influence of stored information has in the determination of the position of the line. The storage cog is the following gear; it houses our memories and life experiences. This cog affects how we respond to new information based on the experiences and wisdom we've gained thus far in life. When someone has dementia, access to memory gradually diminishes until all that is left is the person's physical presence. As time passes, it might become challenging to bring memories to the conscious level. Such memory loss and the capacity to filter information processing at the conscious and unconscious levels imply that stored information is crucial for advancing in life. The distribution cog, which connects to the storage cog and the acquisition cog, comes last. Information can be distributed externally with individual values accumulated during the process, or it can enter the acquisition cog where further information can be sought to supplement that already possessed, seeking proof. Whether or not that is intended, your values and biases will be communicated simply by your facial expression and the way you stand or walk toward or away from someone. In fact, recent studies claim that forecasting the weather has been less accurate because of decreased air travel linked to the coronavirus epidemic and the lack of continual data from in-flight sensors. People have been known to utilize You Tube Tm to construct entire homes or make sourdough bread without any prior baking knowledge, much alone locate health-related information on various social media platforms. How individuals, patients, and professionals can assess the accuracy and robustness of the information they find presents a challenge, particularly in relation to health and social influencers. Saigal thought about how easy it was to get access to health information at the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic, particularly in western cultures, where 74% of knowledge influence came from news organizations and only about 1% from official health and science sites, which could have led to incorrect understanding and the spread of false knowledge, misinformation, or disinformation. Based on how well people are able to process swaying information at the conscious or unconscious level, a perfect storm seems to be brewing. The term infodemic has entered our lexicon to describe a deluge of information that may mislead and polarise viewpoints. There is a clear need in the field of health and care professional working to calm the storm and give practitioners the ability to not only be digitally capable but also intelligently influence knowledgeable, which calls for a health professional to understand the patient's perspective and check their perceptions of the information being exchanged in a care setting. Complex challenges, yet important to encourage wise knowledge impact, include building upon a person's stored information, their life experience, and making sure that the boundary between conscious and unconscious processing is properly positioned. After many years of professional experience, it is relatively easy to evaluate the person you are caring for and have a sixth sense that a deeper look at the situation is necessary. But how can a healthcare student who is encountering this situation for the first time—or, for that matter, a patient develop this kind of professional curiosity? This is where education for the practitioner and the patient is necessary, and given how closely human communication and information technology are related, perhaps it is time to combine the two? As was previously mentioned, we all have our own biases that we have established throughout the course of our lives. Do we take this into account while communicating with patients, their loved ones, and friends? Does the patient automatically accept that the healthcare provider is providing the right information for their condition, or do they bring information they have learned from other sources through digital media that is in conflict with the professional advice? If so, how might this affect the patient's trust in the care relationship? How should communication efficacy and trustworthiness be measured? Who uses a blog to describe the components of trust and the duties of information providers? Any conversation may contain sensitive topics that are not apparent until the topic in question is touched. How do these biases, which operate as entry points into the practise of medicine and as indicators of reliability, impact information sharing and communication in these contexts? Is there now a case for healthcare professionals to adopt an outreach approach using social media to extend the information and care support to those with whom therapeutic relationships have formed outside the hospital walls, as was initially considered through using information prescriptions? The coronavirus hospitalizations have once again shown how important communication is in the caring environment. At their most basic level, information and communication do indeed seem to be simple ideas, but as social media has grown in popularity and accessibility to information has increased, there is a larger risk of patients receiving inaccurate information. The humanistic information model relates to both professional activity communicating with those in their care and all individuals determining their conscious and unconscious processing of information, which may affect their understanding of the care offered. Such access is a complicating factor entering biases that all health and care practitioners need to understand. As technology advances, we will need to be more sceptical when accepting influenced information and the emergence of deep fake computer-generated personas of respected figures. As the focus of healthcare shifts to the patient and consumer, it is critical to recognize the influence of social media influencers in their accurate or inaccurate presentation of a wide range of viewpoints, which has the potential to engender bias for both the patient and the healthcare professional, complicating and obfuscating the communication processes. Although it is unlikely that the infodemic can be stopped, there are measures to control it. In this essay, some of the issues that health and care workers should think about when speaking with patients have been described. It is acknowledged that more work needs to be done in this area to ensure that the role of influencers in determining health and care bias among patients and qualified health care providers in the 21st century patient care information, misinformation, and disinformation is recognized.