A journey from suffering and stress to hope: A staff-parent intervention project at a pediatric nephrology unit

2 Israel Academic College, Ramat Gan 52275, Israel, Email: %20tarabeih1969@gmail.com

Received: 21-Nov-2017 Accepted Date: Dec 13, 2017; Published: 21-Dec-2017

Citation: Tarabeih M, Awawdi K, Rakia RA. A journey from suffering and stress to hope: A staff-parent intervention project at a pediatric nephrology unit. J Nurs Res Pract. 2017;1(1):21-24.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Purpose: The practical, emotional and financial burden on low-to-moderateincome parents of children in hemodialysis is painfully heavy.

Design and methods: An expert project leader experienced in leading groups in clinical treatment and in crisis was hired to lead an intensive short-term intervention designed to assist the parents develop a problem-and-emotion-focused coping style. The leader also worked with unit nursing staff to give them the resources and techniques to support the parents after the intervention ended.

Results: Parents developed a degree of hope and cohesion. They no longer felt alone in their struggle. Staff, shocked at what they heard from parents, realised they had to understand the family situation the parents and children were coming from in order to nurse sensitively and supportively.

Introduction

The burden of care on families of children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is very heavy. The diagnosis and the ensuing care severely disturb the mental and functional equilibrium of both child and family [1]. The family is forced, frequently for the first time in its life, to handle the meaning of acute crisis, which is likely to become, with time, chronic. Without professional guidance, a supportive hand and an attentive ear many families sink into incapacity. There is an essential need to restore the family’s sense of equilibrium. The situation requires the child and his parents to find ways of coping; to adapt to the grave change in their lives, to the sorrow and grief for the child’s loss of health. They need to find means for handling present fears and doubtful expectations. Gaps in literature reveal that there is a lack of support for empirically tested interventions that can help the parents, siblings, and families of chronically ill children [2]. This paper reports how the nursing staff of one pediatric nephrology unit in Israel created an evidence-based intervention to not only support the parents of children suffering from chronic renal failure but also provide the nurses themselves the understanding and techniques to maintain this support once the intervention had ended.

Literature Survey

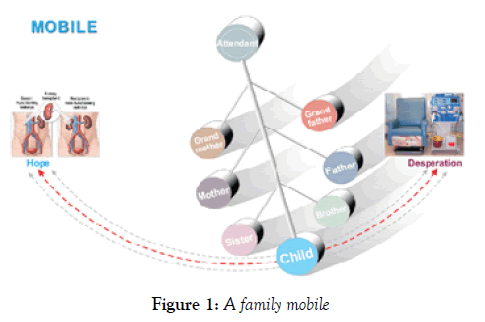

One can compare a family to a mobile—when the wind moves one of the parts the other parts necessarily move with it. A serious health change in one family member sweeps the others up with it. A child with a grave chronic disease, in addition to requiring long-term medical and nursing care, must also get prolonged care from their parents. The family will usually perceive this as stressful, changing other family members’ roles, the overall family lifestyle and, sometimes, even its values and norms. According to family systems theory, the child cannot be the only one affected by the illness. Within the larger family system, subsystems, such as the parent-child or marital relationship systems, all interact with each another and often will negatively register this stress [3].

Chronic kidney disease and its treatment with hemodialysis is terribly wearing, engendering continuous psychosocial stress both for patient and family [4-6]. The stress is the result of perceived damage to the concept of family life, pessimism as to the child’s ability to reach independence, and the child’s specific difficulties [7-9]. Parents, especially mothers, report that the unrelenting stress sets up a negative long-term effect.

To manage the stress of their child’s disease parents, have to find a way to cope. However, little research attention has been paid to such coping strategies. A qualitative metasynthesis has found that patients need the skills to manage three processes: attending to the child’s needs arising directly from the illness, actuating and managing social support resources, and finding a way to live with the illness [10]. The devastating news of their child’s diagnosis may include a potentially shortened life expectancy. Although some families demonstrate resilience in the face of such stressors, the demanding treatment regimen and the shifts in family roles, responsibilities and resources may negatively impact family functioning. Dysfunction and psychopathology are possible outcomes.

Parenting stress has a significant impact on the entire family. The negative consequences associated with it are most commonly depression, anxiety, decreased confidence in parenting skills, and behavioral problems in children. High parenting stress has been associated with poorer psychological adjustment in both family careers and the children they care for. The conclusion must be that parenting stress is an important target for future intervention [3]. If parents can successfully manage the stress associated with their child’s chronic condition, they may be able to help their family adapt to living with an uncertain illness trajectory. If parents can learn how to interpret their child’s reactions to stressful situations, and be given information on how to appropriately respond to those reaction behaviors, then the child will be better equipped to cope with the difficult situations to come.

Chronic patients need instrumental, psychosocial and relational support from health-care professionals, family/friends and fellow patients. Relational support is at the center of the support needs and fuels all other types of support [11]. The Scholten et al. study supports the efficacy of a protocolbased, group intervention for children and parents. Effects persisted over time and this was mainly attributed to the involvement of parents in the intervention. Providing access to multidisciplinary care for children can prevent the development of emotional and behavioral problems secondary to the disease [12].

Another survey points to the importance of the family context to the quality of life of chronically ill children. It clearly showed that the quality of life of children and their parents is closely related and that their perception of the disease as a burden translates into the way they cope with that burden. The solution reported in this case, characteristic of ‘family-centered care’, was tailored health care provided by a multidisciplinary team in an outpatient setting where there was sufficient room to develop the communication and support needed by both children and parents. Expert interventions aimed at promoting the psychosocial health both needed. Extending care to the child’s family is based on the understanding that (a) the family is the child’s primary source of strength and support and (b) that the child’s and family’s perspectives and information are necessary for clinical decision-making by physicians, nurses and other health professionals [13].

The majority of intervention studies found in the literature which include both children and their parents are educational programs for children with epilepsy, whose focus is on providing medical knowledge to parents. The limited psychosocial support that may have been offered to families by nurses as part of the intervention was not measured. This is clearly an area where there is a significant need for further research. The intervention project reported here is the first in Israel in which a hospital pediatric nephrology unit organized itself to offer emotional-psychological support and guidance to the parents of children on dialysis.

The Project

The pediatric nephrology unit at Mayer Children’s Hospital in Haifa provides chronic dialysis treatment to children from all over northern Israel. At the time the project reported here began, in November, 2011, fourteen children were in treatment, all either toddlers aged 1.5-3.5 years or teenagers, aged 11-18. About one third of parents spoke Arabic, one third were Hebrew speaking, and one third came from the former USSR but the Arabic and Russian speakers could all manage in Hebrew too. All came from low-to moderate income backgrounds. The children came for dialysis four to six times a week and each visit meant a stay of about five hours in the unit. The families came, as noted, from all over northern Israel so that some had journeys of an hour to an hour-and-a-half there and back, a total of 7-8 hours away from home for each dialysis session.

The Mayer unit was staffed at this time by a medical director and houseman, a veteran male nurse manager (the author of this report) and four or five nurses who each gave one or two days a week to the unit. A social worker attended the unit one-two hours a day.

All CKD children are on dialysis until a kidney for transplant can be found, a period of time ranging in Israel from a few months to three years. Of every fifteen children on dialysis one or two will die waiting for the transplant. For some of the children the Unit becomes a second ‘home’ but the burden on the parents is extremely heavy. Each visit to the unit takes most of a day which means the escorting parent cannot do paid work. Almost all the parents have other children, sometimes several. Frequently siblings turn up with the sick child (to be cared for in the hospital play center). Health care in Israel is universally free but the state does not cover all the concomitant expenses — some medications, special diets, a wheelchair that has to be regularly changed, travel costs—and for low-income parents these unavoidable extra outlays plus the restricted earning time is a very great strain. And this is without speaking of the emotional distress. It is well known that many couples split under the pressure.

As nurse manager in the Mayer unit for some twenty years and the member of staff parents most regularly saw and consulted with about day-to-day issues, I was well aware of the financial and emotional strain the parents suffered under and had frequently raised contributions from wealthy local businessmen and others to help parents in especial difficulties. Frequently I was deputed by parents to explain the meaning and consequences of a child’s illness to kindergarten and school teachers, or to a local rabbi and was consulted on all sorts of personal issues. But I came to feel that the parents needed a more structured and wider-ranging intervention and also that a help project could benefit the unit’s nursing staff too. I took my idea to the unit medical director who was very responsive. Together we approached the charitable arm of a large Israeli pharmacological company who agreed to supply the moderate funding required—for hiring an expert project and group leader experienced in leading groups in clinical treatment and in crisis.

The model

The model chosen for the intervention is designed for handling crisis situations and returning a family to equilibrium, and its intensity of application intends to generate the greatest benefit in the shortest time [14]. Coping is the sum total of all cognitive and behavioral efforts invested by people in order to control, reduce or endure the imbalance between them and what the environment requires. The model’s aim is to explore and support the parents’ powers of regulation and balance and, where intervention is required, assist in restoring an equilibrium Figure 1 [15].

The overall objective of this specific intervention was to attain a family dynamics that would turn the family ‘mobile’ from a negative to a positive direction, locate a new sense of balance and create new sources of joy and achievement. The role of the leader was to listen to every difficulty and pain the parents were willing to expose and provide sensitive containing and emotional support and an unconditional and non-judgmental attentiveness. The premise was that, stuck in the demanding lifestyle enforced on them, parents had difficulty finding a place that offers support and rest.

Coping with a chronic disease is identical to handling grief and bereavement. The group meetings must enable participants to grieve for the loss of their child’s health, their dreams, expectations and hopes, and move on– without pangs of conscience or guilt– from their life before the crisis. The project model is designed to assist the families develop a problem-and-emotionfocused coping style rather than a style of avoidance.

But the project had a second objective—to help the unit staff continue to help the parents once the intense project had ended. In that spirit separate sessions were planned for parents and the professional care team.

Setting up the Project

Before roll-out the nurse manager met with the project leader to plan the project’s detailed format. It was decided that the project would comprise four sessions with the leader and parents and three with the leader and nursing staff, each meeting three hours long (within-term break) and held in a hospital classroom approximately once a week.

In order to respond to participants’ needs and motivate them as much as possible to actively participate, it was decided to use experience-creating techniques, such as group exercises and material aids (see description of meetings). It was also decided that the nurse manager and the unit social worker would apprise unit staff (including the director) of the content of the parent’s meetings after each such meeting. At first, I did not expect to attend the parent meetings in order to allow them the privacy to vent and voice anything they wanted, including criticism of hospital staff, but in preliminary meetings with the parents they opposed this unanimously, insisting that, as the staffer they most knew and trusted and as the one in charge of the nursing staff, and—in their opinion—the one most likely to get any improvement realized, they wanted me to see and know everything.

In those preliminary discussions with the parents I made clear some terms of my own. I felt it important that all the twenty-eight parents took part without exception, and this was to include even those who had separated and divorced. It was my view that all the parents shared in the suffering and so all should share in the relief on offer. All had something to say and things to hear. To avoid them losing any more paid work time, project sessions would be scheduled for evenings and Friday afternoons and would be rescheduled if any parent could not come. I spoke to all 28 parents and secured the agreement of each to attend. And so it turned out—all 28 parents, those still together and those not, attended every leader-parents session Figure 2.

Project process

Session 1: Group leader with nursing staff and Unit director

The project leader defined the workshop’s objectives. Nurses told of their acquaintance with the families and the children, and for the first time there was an opportunity to hear – in an organized and structured way – how each nurse perceived the families as human beings, with their entire range of traits. Nurses spoke/complained of how difficult parents could be, how each one wanted their dialysis appointments scheduled for a time convenient to them, how late they could arrive (which forced nurses to work (unpaid) overtime), how easily they could get angry with staff, how they, the nurses, often felt mistreated by parents who accused them of only defending ‘the establishment’. One after another each nurse poured out their feelings, including some criticism of me for not holding parents more to account for this ‘mistreatment’. But they also–from their acquaintance with the families– raised ideas for intervention, asked the project leader to give them the tools to handle the strain the patients put on them, and expressed interest and curiosity about the project process. I sat and listened but did not speak.

Session 2: The first with the parents

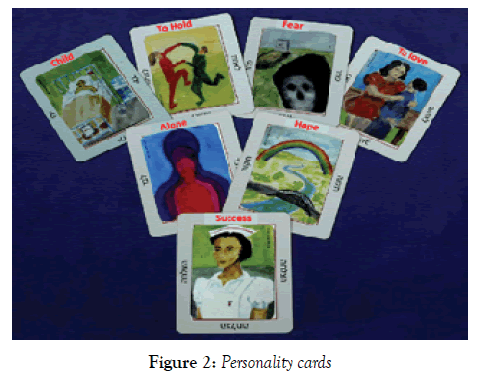

The unit director welcomed the parents, expressing his firm support for the project and its outcomes. As noted, the parents represented many cultures. There were Moslems, Druze and Jews and they ranged in religious practice from the ultra-orthodox to the entirely secular. The first aim was to let parents lament their child’s disease and hear how they mourned the loss of the dream of a healthy child. To help them speak out each parent was asked to pick a card from a deck of ‘Personality’ cards each with a different picture of a child on it. The parents were asked to choose a card that resembled their child and talk about that child over and above the disease and its attendant difficulties; to portray the child as a human being. The meeting was extremely moving and very emotionally loaded. We heard about excruciating money troubles and about couples who separated/ divorced. We heard of the child who told his parents he wished to die in order to spare them all the hardships he was causing them. We heard of parents who never left the house any more except to take their child to the hospital. We heard of healthy siblings who envied their sick brother/sister all the attention they received from their parents. We heard of parents who made every effort to keep their child’s illness secret, fearing that were it publicly known they would never find a marriage partner. However, the meeting also heard accounts of admirable persistence in maintaining routine life in the teeth of huge difficulties, testifying to the powers some parents could find within them.

All parents reacted with intense emotion, according to their own personality and style: introversion, tears, rage, etc. The meeting was often interrupted by weeping (the leader too), anger and difficulty in sharing feelings. Some found it hard to look at their child beyond the disease, and one father left the meeting agitated and weeping. Both the leader and the unit social worker felt that a “block” of stress had been released, that an accumulation of loaded feelings had erupted, which had never been openly addressed before.

Sessions 3-4: With the parents

The intended content of these two sessions was to teach different styles and methods of coping with frustration and difficulties and make use of sources of social support. After the emotional turmoil of the first session, the project team was afraid that the parents would vote with their feet and not show up, but they all came and, moreover, seemed calmer. Some could even smile. To demonstrate different methods of coping with a crisis situation the leader recounted actual examples of how parents in different forms of crisis had found ways to handle their situation.

Each participant was asked to talk about their personal coping style, using references to and examples from the story. A fascinating discussion developed about personality-related styles and situation-dependent styles. The atmosphere was different from the first session, markedly more relaxed despite the in-built difficulties.

Session 5: Last session with the parents: nursing staff also attended

All six of the unit nursing staff attended this meeting because I wanted them to hear with their own ears what the parents had to say. The session focused on observing things from the child’s perspective, while touching on fears of death, of both child and parents. Parents and nurses were requested to divide into three role-playing groups: a parents group, a nurse group, and a children’s group and deliver messages to each other with cards. Some of the messages offered support, love and mutual appreciation. Others were hard and emotionally-loaded, and touched on the desire of some children to die. This exposure of the issue of death, especially at the last meeting, shook the group but also made it possible to express fears and thoughts surrounding it.

The project leader explained to parents that their one essential task was to hang on until the transplant arrived, that they had to find a way to live together and preserve hope until that day. She set out practical examples of how this might be achieved.

Parents urged the unit staff sitting with them to understand the home situation they were coming from, how hard it was just to get to the unit on time for their appointments, and appreciate where the anger they sometimes vented against staff came from. Some parents also voiced the fear that even if they struggled through to day of the transplant the transplanted kidney would not last long. I concluded the meeting by citing many instances of transplanted kidneys working well for twenty, thirty, even forty years provided they were well cared for.

Session 6: Leader and career team (including the unit director)

Every member of staff, without exception, was in shock at what they had heard about the multiple stresses parents were struggling against. No one had had any idea of just how hard their plight was. “I knew some of what they were dealing with, but I didn’t know just how terrible it was…” Several had not been able to sleep after hearing what they heard. “We have to have the flexibility to ask the mum each day how are they that day, how’s the kid, how’s their other kids.” Nurses asked the leader for guidance in ways to help the parents within their roles in the unit.

The project leader legitimized the staff’s exposure of their own emotions. She raised ethical dilemmas attached to the long-term treatment of children sick with a complex chronic disease and what this did to the families; how to cope with the death of a child attending the unit. Nurses were invited to raise personal, emotional and group dilemmas concerning the contact between them, the child patients and their parents. Questions were raised as to the boundaries operating within a small unit, as to how staff could communicate about feelings on key issues. Nurses voiced individual preferences.

Session 7: Leader and career team (including the unit director)

The project leader explained to staff that the essence of their function in the unit was to deliver the parents and children hope. They had to let parents have their voice even if it was one of anger, knowing that the anger was not really addressed against them, that it would soon pass, and the parent would apologies and calm down. She set out techniques for coping with anger, for displaying sensitivity, understanding and availability.

Clear relationship boundaries between nurses, parents and children were outlined and tools and emphases for improving staff behavior with parents were also provided (the nurse manager and the unit social worker added their input into this aspect).

The group leader’s brief evaluation of the intervention program was as follows: The process of group guidance over a number of sessions had demanded willingness, time, openness and courage from the parents, and required that they make themselves available both physically and emotionally for a complex and challenging process with unknown outcomes. Despite the difficulty in opening up heavily-loaded issues such as anger, denial, isolation, depression, acceptance, loss, couple-relationships, separation and death, the parents were able to find the inner moral strength to cope with these subjects. The intervention had enabled the parents to open up on issues where silence and avoidance had been their major methods of coping. They had learnt that these subjects could be handled actively. The project had helped them move in the direction of hope.

That all the parents, as well as the whole staff, had given so much of themselves to the sessions, that every parent had come to every parent session, were expressions of the parents’ faith in the caregiving team and of the staff’s commitment to the unit. The parents had expressed their appreciation by voting with their feet.

Since the Intervention

Practical measures were taken straightaway. The unit director had been so struck and shocked by what he had heard (“We know the clinical and nursing side of the business but we don’t see what they go through outside here as soon as we make our diagnosis”) that he concluded with me that henceforward every new child patient/ parent dyad entering the unit would receive a complete briefing on the expected course of the illness and its treatment, and on their rights to support, practical, financial and emotional, both within the unit and outside. They were told to bring any sort of problem to the unit and unit staff would try to help. It was to be emphasized to them that there was light at the end of the tunnel. For my part, I increased my efforts at raising charitable donations from the wealthy.

Secondly, as soon as there were four to five new patients the intervention project was to be repeated, for both parents and staff. The same pharmacological company again funded each time the hire of a professional group/project leader. (Sadly, and surprisingly, we have seen no sign that any of the other pediatric dialysis units in Israel has followed our example.)

Three months after the first project ended the entire unit staff were gathered together to evaluate its effects and results. Nurses reported that they had developed greater understanding of and sensitivity towards the parents, that they had the patience now to see if a parent and/or child arrived irritable and angry where that anger originated. They felt also that the parents were calmer and appreciative of the nurses’ more sympathetic attitude and behavior. One parent had said: “We see that you see our anger”. Nurses felt that it was important that they took part in workshops that doctors, social workers and psychologists attended in order to appreciate the complexity of the challenges that the dialysis unit parents had to deal with.

For my part, I knew from my close personal acquaintance with the parents that some degree of group coherence had appeared among them, and also between them and the unit team. The project had delivered the message that the parents were not alone, that support was available. Each parent had also seen and heard with their own eyes and ears that they were not alone in their suffering, that many other parents were ‘in the same boat’. They had heard the ways other parents were finding to cope. An unexpected benefit of the project was that unmarried nurses and male nurses learnt a lot about the world of mothering and its inner workings, which made them much more sensitive nurses.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study make a useful contribution to nursing practice. Nurses need to recognize that the parents of children on dialysis require additional education and support beyond the medical management of the child’s condition. Nurses, and other hospital professions, need to learn the many ways in which they can support these families and help teach them strategies to facilitate coping with their child’s illness and suffering.

The project has demonstrated the importance of short-term crisis intervention, that even a time-limited but intense intervention has the power to markedly improve the quality of family life.

Acknowledgements

The two senior co-authors wish to warmly acknowledge the contributions to this project of the management of the Mayer Children’s Hospital, Rambam Campus, Haifa, of the director and staff of its Pediatric Nephrology unit, and of all the parents who took such a bold part in the project.

Learning Outcome

• The projects essence was to give parents hope and the sense they were not alone.

• Nursing staff benefitted from the intervention as much as the parents.

• The multiple stresses on parents came as a severe shock to all staff.

• To be good doctors and nurses staff have to learn these stresses.

• Staff and unit have to learn to give non-clinical support.

REFERENCES

- Wiedebusch S, Konrad M, Foppe H, et al. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial strains, and coping in parents of children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(8):1477-85.

- Anderson T, Davis C. Evidence-based practice with families of chronically ill children: A critical literature review. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2011;8(4):416-25.

- Cousino MK, Hazen RA. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness : a systematic review, J Pediatr Nurs. 2013;38(8):809-28.

- Folkman S, Moskowitz-Tedlie J. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol. 2000;55:647-54.

- Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, et al. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. Am Psychol. 2000;55:99-109.

- Berkman L. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843-57.

- Ben-Zur H, Rappaport B, Ammar R, et al. Coping strategies, life style changes, and pessimism after open-heart surgery. Health Soc Work. 2000;25:201-9.

- Soskolne V. Single parenthood, occupational drift and psychological distress among immigrant women from the former Soviet Union in Israel. Women Health. 2001;33:67-84.

- Bisschop MI, Kriegsman DMW, Beekman ATF, et al. Chronic diseases and depression: the modifying role of psychosocial resources. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:721-33.

- Ooi KL, Ong YS, Jacob SA, et al. A meta-synthesis on parenting a child with autism. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:745-62.

- Dwarswaard J, Bakker EJM, Van Staa A, et al. Self-management support from the perspective of patients with a chronic condition: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. 2015.

- Scholten AM, Last BF, Maurice-Stam H, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial group intervention for children with chronic illness and their parents. Pediatr. 2013;131(4):1196-203.

- Sikorova L, Buzgova R. Associations between the quality of life of children with chronic diseases, their parents’ quality of life and family coping strategies. Central European Journal of Nursing & Midwifery. 2016;7(4):534-41.

- Carver CS, Scheier M. Situational coping and coping dispositions in stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:184-95.

- Geary CD, Flinn MV. Sex differences in behavioral and hormonal response to social threat: commentary. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:745-53.