An unusual case of uterus didelphys in an infertile mare with mosaic X-chromosome aneuploidy

2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ontario Veterinary College, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, Email: ahmadibahare474@gmail.com

3 Departmento de Producción Animal, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico, Email: dvilla@cucba.udg.mx

4 Karyotekk Inc., Box636 OVC, University of Guelph, Guelph Ontario, Canada, Email: mouhamadou.diaw@umontreal.ca

Received: 26-Mar-2018 Accepted Date: Apr 17, 2018; Published: 01-May-2018

Citation: Murcia-Robayo RY, Raggio I, Ahmadi B, et al. An unusual case of uterus didelphys in an infertile mare with mosaic X-chromosome aneuploidy. J Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;2(2):55-58.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

A 3 year old Irish Cob maiden mare of normal size was referred at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vétérinaire, University of Montreal, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine because of fertility problems and the possible presence of two cervices. The external genitalia appeared normal. Examination of the internal reproductive tract revealed normally functioning ovaries and two tubular structures compatible with cervices were identified on the pelvic floor. Endoscopy of the cranial vagina confirmed the presence of two cervices. Chromosome analysis revealed mosaic aneuploidy of the X chromosome (mos 63, X/64, XX). No treatment was available for either of the anomalies diagnosed and the mare was discharged. This report highlights the importance of using diagnostic tests in addition to clinical examination in cases of equine infertility.

Keywords

Mare; Uterus didelphys; Mosaicism; Infertility; Karyotype

Abbreviations

UD uterus didelphys

The term Disorder of sexual development (DSD) includes a very broad spectrum of sexual pathologies well described in humans and domesticated animal species. In horses, DSDs are not uncommon and in the clinical context, they are expected to cause reproductive problems and possibly lead to infertility. Normal development of the internal female reproductive tract involves a series of complex molecular and biochemical interactions that lead to differentiation of the Müllerian ducts and the urogenital sinus [1]. During this period, the posterior portion of each Müllerian duct undergoes a dynamic process of growth, migration and differentiation and eventually fuses with the corresponding contralateral paramesonephric duct, resulting in formation of the uterine body and cervix as well as the cranial portion of the vagina [2]. Congenital abnormalities affecting the uterus and cervix result from abnormal fusion or regression of the posterior portions of the Mullerian ducts [3,4]. Varying degrees of these abnormalities, including a complete uterine septum, cervical duplication with a normal or septate uterus, and a blind-ended cervical canal, have been reported in mares [5]. Most of the reported cases have involved Clydesdale, Shire and Suffolk Punch draft horses [6-8] and the mares affected were mostly fertile and delivered foals uneventfully [9]. However, in none of these reported cases, the cytogenic analysis was performed. The present report describes a uterus didelphys in an infertile mare with mosaic X chromosome aneuploidy.

Case

A 3 year old Irish Cob maiden mare of normal size was referred at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vétérinaire, University of Montreal, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, for investigation of fertility problems and the possible presence of two cervices. The mare was not in foal despite being covered by two fertile stallions on four occasions during the same season. On examination, the external genitalia were normal and there was no clitoral enlargement. Transrectal palpation and ultrasound examination of the entire reproductive tract using a 7.5 MHz linear probe were performed. The ovaries were of normal size, and examination of their surface and the ovulation fossa revealed no anomaly. The ultrasound examination revealed normal ovarian structures and follicles of various sizes in both ovaries. A dominant follicle (42 mm × 36 mm) was visualized in the left ovary. Uterine edema with a “wagon wheel” appearance was identified on ultrasound examination of cross-sections of the uterine horns and graded as 2/3.

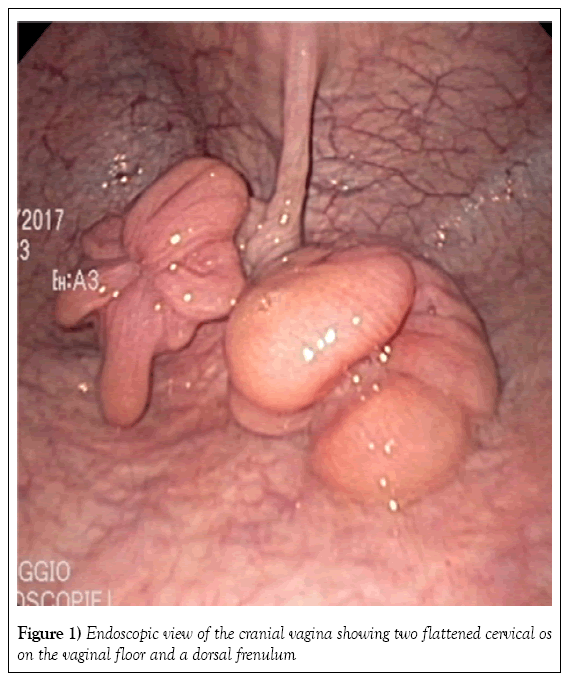

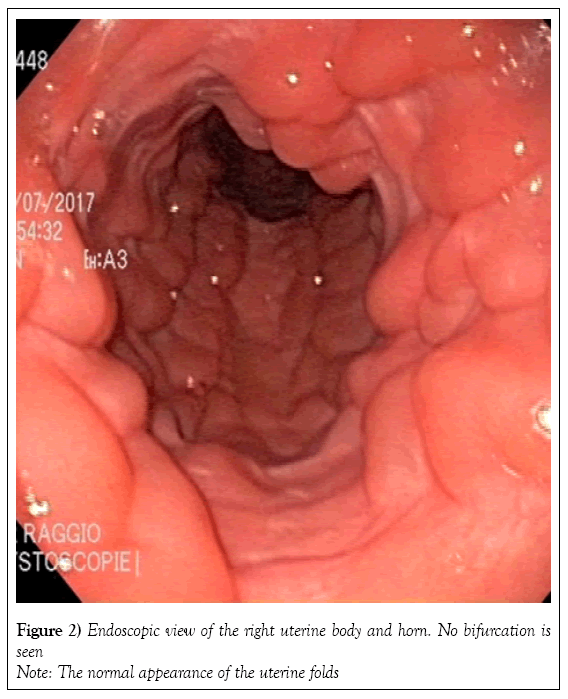

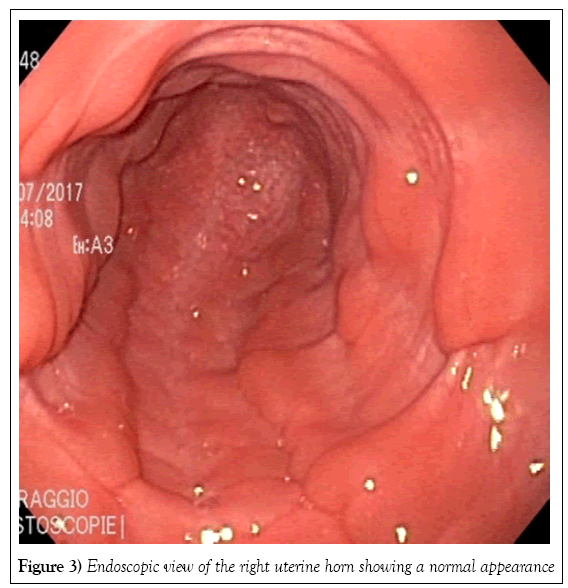

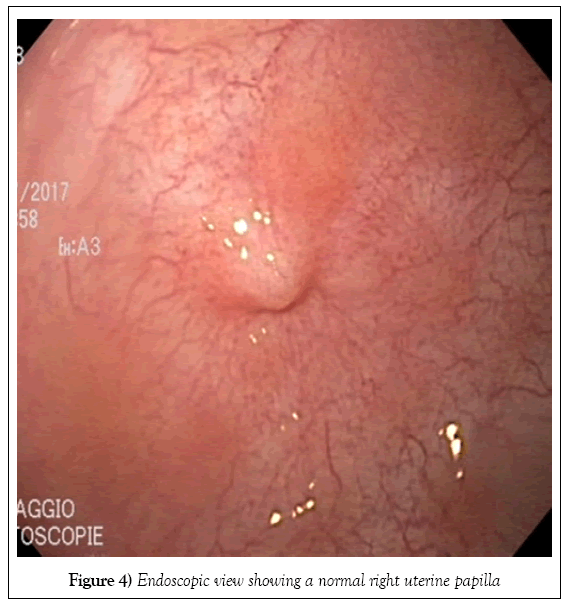

Two tubular structures compatible with the presence of two cervices were identified by transrectal palpation of the pelvic floor. The vagina and uterus were visualized on fiberoptic endoscopy. The caudal vagina and vestibulovaginal fold were normal. Endoscopy of the cranial vagina confirmed the presence of two cervices (Figure 1). Digital palpation revealed that both structures led into a uterine cavity. The endoscope was first passed gently through the right cervix into the uterus. The uterus was distended with air to allow visualization of its lumen (Figure 2) and the cervix was held closed by the operator’s hand around the endoscope to maintain insufflation of the uterus. The endoscope was passed through the cervix all the way to the uterotubular junction at the tip of the horn, which also had a normal appearance (Figures 3 and 4). There was no bifurcation of the uterus, and the mucosa was normal in appearance. The endoscope was then passed throughout the left cervix. The corresponding portion of the uterus was not distended; after being filled with air, it showed the same normal appearance as the right cervix. There was no communication between the right uterus and the left uterus.

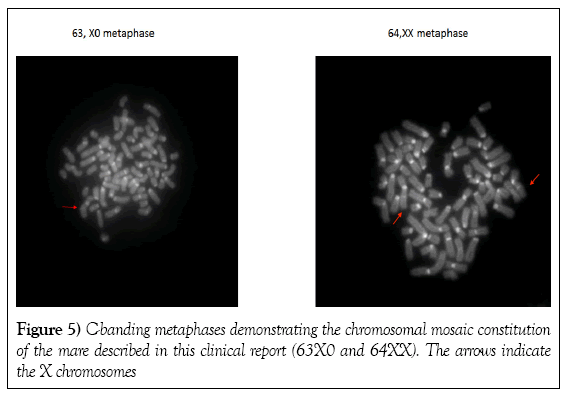

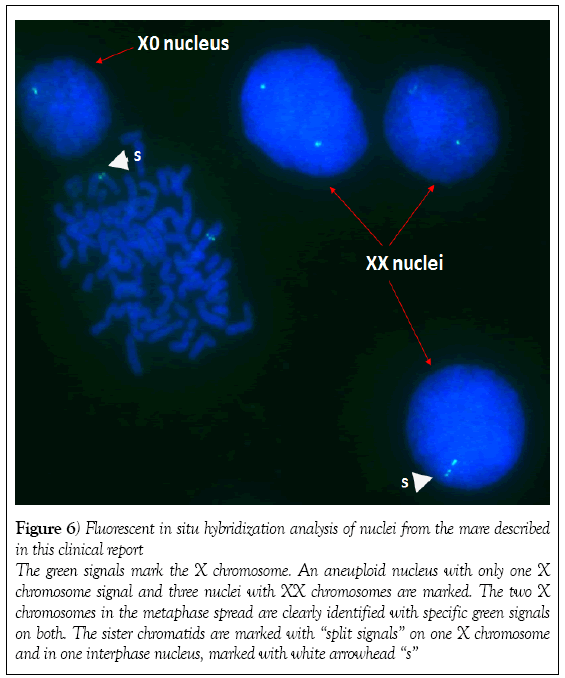

Peripheral blood was collected into sterile sodium heparin tubes. Lymphocytes were cultured under conventional conditions [10] and the karyotype was analyzed using fluorescent C-banding and X-chromosome specific fluorescent in situ hybridization. Screening of 86 metaphase spreads using the fluorescent C-banding approach showed that 72 cells (84%) had a normal 64,XX chromosome constitution and 14 (16%) had an abnormal 63,X karyotype. Fluorescent in situ hybridization of the interphase nuclei of 502 cells revealed that 430 (86%) had a normal two X chromosomes and 72 (14%) had one X chromosome (Figures 5 and 6). On average, the mare had a 14.6% rate of X chromosome monosomy. As a control samples from a normal fertile mare processed in the same way (e.g. fluorescent C-banding analysis) were found to have two X chromosome in 100% of metaphase and

Figure 6: Fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis of nuclei from the mare described

in this clinical report

The green signals mark the X chromosome. An aneuploid nucleus with only one X

chromosome signal and three nuclei with XX chromosomes are marked. The two X

chromosomes in the metaphase spread are clearly identified with specific green signals

on both. The sister chromatids are marked with “split signals” on one X chromosome

and in one interphase nucleus, marked with white arrowhead “s”

Discussion

Uterus didelphys is a congenital anomaly of the female reproductive tract, except in marsupials and lagomorphs, where it is considered normal. The condition results from failure of fusion of the lower segments of the paired Müllerian ducts, resulting in two uteri and two cervices. Very few clinical cases of UD have been published, suggesting a very low incidence of this anomaly. Abnormalities of the female reproductive system are generally not accompanied by clinical signs, unless an anatomic modification or pathology, such as a tumor, is present [11,12]. Pregnancy loss during the embryonic stage or later during fetal growth would be a concern in a mare with UD. In a normal mare, movements of the embryo throughout the entire uterine cavity before immobilization at around day 16-17 after ovulation are essential for maternal recognition of pregnancy. Any limitation or restriction of these movements would prompt release of luteolysin, which would result in the destruction of the corpus luteum and a return to estrus [13]. In a mare with UD, movements of the equine embryo would be limited to only half of the uterus, so the pregnancy would be compromised. There would also be concern about the risk of abortion during subsequent fetal growth, because of the significant reduction in the surface of the placenta [9] and a lack of space for the fetus to grow and develop [7,14]. Nevertheless, there are reports of live and healthy foals being delivered by mares with various Müllerian duct disorders [7,9], including a case of a small viable foal born to a Clydesdale mare with UD that was treated with oral progesterone for the full duration of the pregnancy [9].

Uterus didelphys in domestic animals is mostly an incidental finding, and routine transrectal palpation and ultrasound examination of the internal reproductive tract in a mare does not necessarily facilitate the diagnosis of UD. In the present case, the anomaly was diagnosed primarily by transrectal palpation and from the history provided by the referring veterinarian. Additional tests, including vaginoscopy and hysteroscopy, may be more conclusive and vaginoscopy should be routinely included in the assessment of breeding soundness. Three-dimensional ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging have been reported to aid visualization of UD and other malformations of the internal reproductive system in human patients [15,16]; however, implementation of these technologies might be difficult in a practice that treats large animals. While some corrective procedures to improve fertility have been described in human patients with UD [16], the authors are not aware of any such treatments in domestic animals.

Since there was no evidence that the UD in our patient was directly linked to infertility and because most mares with abnormalities affecting the sex chromosome have a normal phenotype [17], a chromosome analysis was performed and revealed 63,X/64,XX mosaicism, with 14.6% of cells having only one X chromosome. The abnormal 63,X cell line identified in this horse likely resulted from segregation errors of the sex chromosomes during the initial development of the zygote (postzygotic mitotic nondisjunction) [17]. The 63,X chromosomal constitution is analogous to Turner’s syndrome in humans (e.g. 45,X0). It is one of the most common anomalies described in the horse and is often implicated in equine sexual development disorders [19-21]. The typical 63,X mare is small in stature and has extremely small ovaries and a flaccid infantile uterus. The external genitalia may be smaller but normal in appearance with no clitoral hypertrophy. An affected mare shows persistent anestrus or irregular periods of behavioral estrus and may stand to be mated. In the literature, a large percentage of mares with X monosomy described had mosaicism. Although nearly all 63,X mares are infertile and exhibit characteristic phenotype, mares with a mosaic karyotype (mos 63,X/64,XX) are not always small in stature, and some have been reported to produce a foal with the degree of fertility being correlated with the percentage of normal cells present [17,22,23]. To date, there is no evidence of inherence in the offspring of mos 63,X/64,XX mares [17,18] and studies of the karyotypes in descendants of these mares might be helpful in the decision whether to keep breeding from such individuals.

The mare described in this clinical report was normal in appearance. The uterine horns were normal in size, and the ovaries had normal follicular activity. The mare had a history of normal estrus cycles but never having been in foal. However, no formal examinations for pregnancy had been performed, and the mare was simply declared not to be in foal each time she came back into estrus following attempts at natural breeding. This could be related to a failure of maternal recognition of pregnancy in response to movements of the embryo being limited to one uterine horn instead of the entire uterus. An ultrasound examination 14 days post ovulation and supplementation with synthetic progesterone would have been suitable in the event of pregnancy. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first case of UD in a mare with mosaicism. Further tests, including a skin biopsy to obtain connective tissue for development of a fibroblast cell culture and explore other possible structural chromosomal abnormalities in this patient were offered but were declined by the owner.

Conclusion

In conclusion, UD is a rare congenital disorder of the female reproductive system in mammals, including horses. Diagnosis by transrectal palpation and ultrasound examination is not always conclusive and requires further investigation, such as vaginoscopy or hysteroscopy. When diagnosed, assisted reproduction techniques may be the best option to optimize the chances of obtaining a healthy live foal. When a phenotypically normal mare is presented with a complaint of fertility problems despite thorough clinical examination, karyotyping is strongly recommended to rule out a chromosomal abnormality.

REFERENCES

- Amesse LS, Pfaff-Amesse T. Mullerian duct anomalies. WebMD. 2016.

- Hyttel P, Sinowatz F, Vejlsted M, et al. Essentials of domestic animal embryology e-book: Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009.

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's pathology of domestic animals E-book. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015;358.

- Larsen W, Brauer PR, Schoenwolf GC, et al. Human embryology. Paris, France: De Boeck Superieur. 2017. In French.

- Card C. Congenital abnormalities of the cervix in mares. Equine Vet Educ. 2012;24:347-50.

- Blue MG. A uterocervical anomaly (Uterus bicorpor bicollis) in a mare and the manual disruption of early bilateral pregnancies. N Z Vet J. 1985;33:17-9.

- Volkmann D, Gilbert R. Uterus bicollis in a Clydesdale mare. Equine Vet J. 1989;21:71.

- Hurtgen J. Abnormalities of cervical and vaginal development. In: McKinnon AO, Squires EL, Vaala WE, Varner DD, eds. Equine reproduction, Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ. 2011;2.

- Hurtgen JP. Congenital abnormalities involving the cervix and uterus. In: Samper J, Pycock J, McKinnon A, eds. Current therapy in equine reproduction. Saunders Elsevier; St Louis, MO. 2007;128-9.

- Villagómez DA, Lear TL, Chenier T, et al. Equine disorders of sexual development in 17 mares including XX, SRY-negative, XY, SRY-negative and XY, SRY-positive genotypes. Sex Dev. 2011;5(1):16-25.

- Morris P. An unusual case in swine of uterus didelphys. Br Vet J. 1954;110:205-7.

- Gao J, Zhang J, Tian W, et al. Endometrial cancer with congenital uterine anomalies: 3 case reports and a literature review. Cancer Biol Ther 2017;18:123-31.

- Ginther OJ. Equine pregnancy: physical interactions between the uterus and conceptus. Proc Am Assoc Equine Pract. 1998;73.

- Jobert M, LeBlanc M, Pierce S. Pregnancy loss rate in equine uterine body pregnancies. Equine Vet Educ. 2005;17:163-5.

- Hundley AF, Fielding JR, Hoyte L. Double cervix and vagina with septate uterus: An uncommon Müllerian malformation. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98(5 Pt 2):982-5.

- Rezai S, Bisram P, Lora Alcantara I, et al. Didelphys uterus: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:865821.

- Kjöllerström H, Collares-Pereira M, Oom M. First evidence of sex chromosome mosaicism in the endangered Sorraia horse breed. Livest Sci. 2011;136:273-6.

- LeBlanc. An approach to the diagnosis of infertility in the mare. North American Veterinary Conference (USA). 1996.

- Bruère A, Blue M, Jaine P, et al. Preliminary observations on the occurrence of the equine XO syndrome. N Z Vet J. 1978;26:145-6.

- Bugno M, Słota E, Kościelny M. Karyotype evaluation among young horse populations in Poland. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2007;149:227-32.

- Szczerbal I, Switonski M. Chromosome abnormalities in domestic animals as causes of disorders of sex development or impaired fertility. Insights from Animal Reproduction: InTech. 2016.

- Lear T, Villagomez DAF. Cytogenetic evaluation of mares and foals. In: McKinnon AO, Squires EL, Vaala WE, Varner D, eds. Equine reproduction. 2nd ed. Wiley Blackwell: Chichester. 2011:1951-62.

- McCue P, Ferris R. The abnormal estrous cycle. Equine Reprod. 2011:1754-68.