Anesthesia factors in urologic surgery

Received: 18-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. pulacr-22-5269; Editor assigned: 20-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. pulacr-22-5269; Accepted Date: Jul 12, 2022; Reviewed: 04-Jul-2022 QC No. pulacr-22-5269; Revised: 10-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. pulacr-22-5269; Published: 15-Jul-2022, DOI: 10.37532. pulacr.22.5.4.10-12

Citation: Shukla T. Anesthesia factors in urologic surgery. Anesthesiol Case Rep. 2022; 5(4):10-12.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Numerous urologic procedures are performed, and as the aged population has grown, so have the number of cases. The majority of urologic procedures are difficult to execute due to the small and constrained operating room. In order to deliver the best anesthetic during surgery, a thorough understanding and strategy are needed because the senior population is also at risk for perioperative problems.

Key Words

Nephrectomy; Transurethral surgery; Spinal anesthetic

Introduction

The majority of urologic procedures are carried out using a cystoscope and a minimally invasive approach in a small, constrain- -ed area on older patients with concomitant illnesses. To maximize surgical outcomes, anesthesiologists need to take into account a variety of parameters in addition to providing proper anesthetics, such as age, co-morbidities, functional status, duration of operation, anticipated blood loss, and surgical scope.

Nephrectomy

The usual course of action for Renal Cell Cancer is nephrectomy (RCC). Depending on the features of the tumor, partial or radical nephrectomy may be performed. During nephrectomy, patients are frequently positioned in the lateral decubitus position, putting them at risk for pressure sores, nerve injury, or venous congestion. For instance, the neck should be in a neutral position, the eyes and ears should be shielded from excessive pressure, and brachial plexus injury should be avoided by applying axillary roll to the dependent side.

Robot-assisted nephrectomy has become more and more common throughout the years since robotic surgery was first applied to the surgical profession. The robot system is large and big; thus ample room must be provided. The patient's head needs to be shielded against unexpected impacts with the robot arms because the robot arms' range can be quite extensive. Particularly in an emergency, robot docking may interfere with patient assessment and quick management. Tissue damage during robot docking could result from patient movement [1]. To inhibit movement or muscle contraction, sufficient Neuromuscular Blockade (NMB) should be taken into account.

Cystectomy

The preferred course of treatment for invasive bladder cancer is cystectomy. The bladder may be removed entirely or in part, depending on the type of surgery. There is a risk of bleeding during this protracted, difficult procedure. Between 0.56 L to 3 L of blood are lost on average during cystectomy [2].

Therefore, if necessary, a blood transfusion may be considered. However, in a prior analysis that examined 2,060 patients who underwent radical cystectomy, blood transfusion was substantially related to worse 5-year recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival. Perioperative blood transfusion increased morbidity and surgical site infection, according to another study that included 2,934 patients who underwent radical cystectomy [3].

Comparatively, Abel et al. analysis of the relationship between the time of blood transfusion and outcomes revealed that intraoperative blood transfusion significantly raised the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality, whereas postoperative transfusion did not [4]. Contrary to earlier research, several studies emphasized the little correlation between blood transfusion and outcomes associated with cancer [5]. In the multivariate or adjusted analysis, the link between blood transfusion and increased recurrence and death was no longer significant.

Transurethral resection of bladder cancer

The cornerstone of diagnosing and treating bladder cancer is Transurethral Resection Of Bladder Cancer (TURB), an endoscopic surgery. The shape, size, position, and quantity of tumors can be determined with TURB, which is carried out in an extremely constrained and congested bladder region. During TURB, the obturator nerve that runs near the lateral wall of the bladder may be activated, which could lead to an unanticipated movement of the ipsilateral thigh and an obturator nerve response. Therefore, during TURB, the proper anesthetic should be given to ensure a sufficient operative environment and full resection. TURB procedures can be carried out under either general or local anesthetic. In elderly patients undergoing brief transurethral surgery, general anesthesia with propofol and desflurane gives faster induction and recovery than spinal anesthetic. For a supraglottic airway device or endotracheal intubation, NMB is required.

Additionally, a sufficient depth of NMB is necessary to prevent the obturator nerve reflex, which results in erratic contraction of the adductor muscle. 89 patients who underwent TURB between 1997 and 2007 were examined and studied by Cesur et al. [6]. Succinylcholine, a depolarizing NMB drug, was given to each of the 56 patients who underwent TURB under general anesthesia before resection.

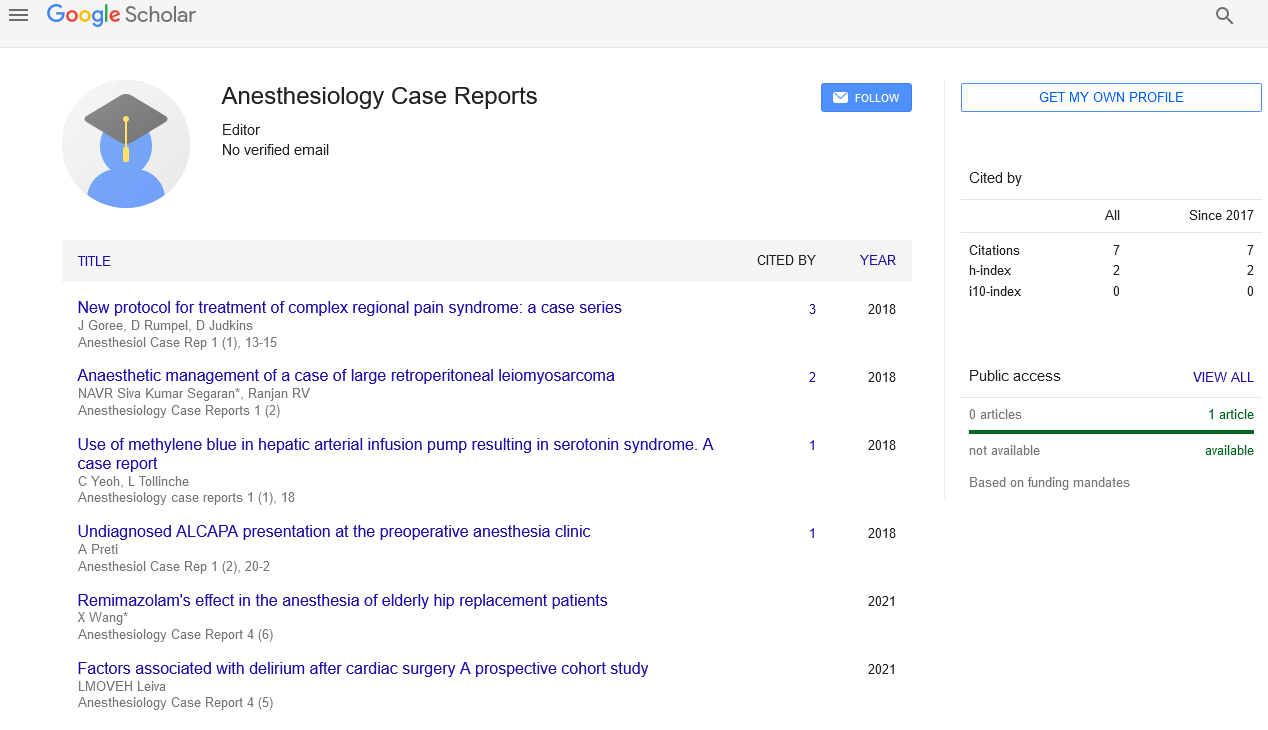

Under spinal anesthetic, numerous transurethral procedures were completed successfully. An effective anesthetic effect with sustained hemodynamic stability was achieved with spinal anesthesia using hyperbaric bupivacaine 12 mg with 3 g of dexmedetomidine or 30 g of clonidine in a prior trial on patients undergoing urologic surgery [7]. Other research indicated that levobupivacaine-based spinal anesthesia provided an adequate anesthetic effect during transurethral surgery [8]. Obturator Nerve Block (ONB) is necessary to prevent obturator nerve response since spinal anesthesia was unable to stop it. In a prior study, the incidence of the obturator nerve reflex was compared between spinal anesthesia and spinal anesthesia combined with ONB, and the results revealed that in the patient who received spinal anesthesia combined with ONB, the incidence of the obturator nerve reflex was lower (40% vs. 11.4%) [9]. Depending on the needle orientation and insertion site, there are numerous ONB procedures. The traditional and inguinal methods to ONB are depicted in Figure 1. The public approach, also referred to as the classic technique, was developed by Labet [10]. The pubic ramus is reached by inserting the needle 3 cm laterally and 3 cm inferiorly from the pubic tubercle. At the obturator foramen, the obturator nerve was cut off [11]. It could be challenging to locate the pubic ramus, the landmark of the traditional technique, in patients who are particularly obese or who have blunt tubercles. The rectum, spermatic cord, and other nearby organs could be damaged by the traditional method.

Pain control and recovery

Mild to moderate pain is typically felt after urologic operations [1]. One of the key elements influencing how well a recovery goes is pain management. Numerous research [12] have looked into different strategies to reduce pain in people undergoing urologic surgery. Transversus Abdominis Plane (TAP) block has been shown in prior research to have positive analgesic effects and to lessen the need for opioids in patients having minimally invasive surgery [13]. Local anesthetics are injected into the tissue between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique. They obstruct the sensory pathways of the anterolateral abdominal wall's intercostal nerves T7–T11, subcostal nerve T12, and ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves L1. To compare the analgesic effectiveness of TAP block with epidural analgesia, Baeriswyl et al. carried out a meta-analysis [14]. The incidence rate of hypotension was much lower and the LOS was shorter in the TAP block group compared to those in the epidural analgesia group, however, there was no statistically significant difference in pain ratings between the two groups on a postoperative day 1 after the procedure.

Conclusion

Elderly patients and patients with a range of diseases are both included in urologic procedures. Therefore, in terms of preoperative assessment, intraoperative treatment, and postoperative care, a general collaboration between the urologist and the anesthesiologist is necessary. Better outcomes, a higher standard of rehabilitation, and greater patient satisfaction result from a tailored, optimized strategy.

REFERENCES

- Cockcroft JO, Berry CB, McGrath JS, et al. Anesthesia for major urologic surgery. Anesthesiology clinics. 2015;33(1):165-72. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Soulié M, Straub M, Gamé X, et al. A multicenter study of the morbidity of radical cystectomy in select elderly patients with bladder cancer. J Urol. 2002;167:1325–8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Linder BJ, Frank I, Cheville JC, et al. The impact of perioperative blood transfusion on cancer recurrence and survival following radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2013;63:839–45. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Sui W, Onyeji IC, Matulay JT, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion in radical cystectomy: analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Int J Urol. 2016;23:745–50. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Abel EJ, Linder BJ, Bauman TM, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and radical cystectomy: does timing of transfusion affect bladder cancer mortality? Eur Urol. 2014;66:1139–47. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kluth LA, Xylinas E, Rieken M, et al. Impact of peri-operative blood transfusion on the outcomes of patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int. 2014;113:393–8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Cesur M, Erdem AF, Alici HA, et al. The role of succinylcholine in the prevention of the obturator nerve reflex during transurethral resection of bladder tumors. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:668–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazi GE, Aouad MT, Jabbour-Khoury SI, et al. Effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine or clonidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:222–7. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Cuvas O, Er AE, Ongen E, et al. Spinal anesthesia for transurethral resection operations: bupivacaine versus levobupivacaine. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74:697–701. [Google Scholar]

- Bolat D, Aydogdu O, Tekgul ZT, et al. Impact of nerve stimulator-guided obturator nerve block on the short-term outcomes and complications of transurethral resection of bladder tumour: a prospective randomized controlled study. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:E780–4. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Labat G. Regional anesthesia: its technic and clinical application. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1922. pp. 249–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A, Greul F, Meibner W. Pain management in urology. Urologe A. 2013;52:585–95. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- De Oliveira GS, Castro-Alves LJ, Nader A, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block to ameliorate postoperative pain outcomes after laparoscopic surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:454–63. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Baeriswyl M, Zeiter F, Piubellini D, et al. The analgesic efficacy of transverse abdominis plane block versus epidural analgesia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11261. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]