Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition further reverses cardiac remodeling as compared to angiotensin inhibition in reduced heart failure patients

2 Hospital Universitario de Elche Vinalopó, Universidad Católica de Murcia, Alicante, Spain

3 Grupo HM Hospitales, Universidad CEU San Pablo, Madrid, Spain

#Equally contribution

Received: 29-Dec-2017 Accepted Date: Jan 16, 2018; Published: 20-Jan-2018

Citation: Gonzalez-Torres L, De Diego C, Centurion R, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition further reverses cardiac remodeling as compared to angiotensin inhibition in reduced heart failure patients. Clin Cardiol J 2018;2(1):6-9.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Reduced ejection fraction heart failure patients (rEFHF) benefited from optimal medical therapy (OMT) including ACEI or ARBs, BBK and MRA. The PARADIGM-HF study showed that angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition (ARNI) as compared to ACEI reduced sudden cardiac death in rEFHF. The effect of ARNI in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not described. Purpose: To evaluate the impact of ARNI as compared to angiotensin inhibition in LVEF and left ventricular diastolic size (LVDD). Methods: We prospectively analyzed consecutive rEFHF patients (n=250) with following inclusion criteria: 1) LVEF, ≤ 40%, 2) NYHA functional class ≥ II 3) 9 months of OMT with angiotensin inhibition (ACEI/ARB), BBK and MRA. 4) Then, ACEI or ARB was changed to ARNI, which was tolerated for 9 additional months. The following parameters were collected by biplane 2D or automatic 3D echocardiogram: LVEF and LVDD. Results: After 9 months with ACEI, patients averaged an age of 69 ± 8 (76% male) and had an averaged LVDD of 62 ± 6 mm and LVEF of 31 ± 6% (80% ischemic) with NYHA of 2.4 ± -0.4. The use of BBK (93%) and MRA (83% vs.81%) was similar before and after ARNI. After 9 months with ARNI, NYHA improved to 1.5 ± 0.7 (p<0.0002), LVDD decreased (60 ± 6 mm, p<0.02) and LVEF increased (36.5 ± 8%, p<0.002). Conclusion: In a mainly ischemic rEFHF population, angiotensinneprilysin inhibition as compared to angiotensin inhibition further reversed cardiac remodeling leading an increase of LVEF, a predictor of sudden cardiac death.

Keywords

Sacubitril-Valsartan; Heart failure; Cardiac remodeling; Left ventricular ejection fraction; Sudden cardiac death

Abbreviations

ICD: Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator; PVC: Premature Ventricular Contraction; rEFHF: Reduced Ejection Fraction Heart Failure; NYHA: New York Heart Association; ACE inhibitor: Angiotensin- Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; MRA: Mineralocorticoid Antagonist; BBK: Beta-Blocker.

Reduced ejection fraction heart failure (rEFHF) patients have benefited from blocking three systems (renin-angiotensin pathway, adrenergic system and aldosterone pathway) with: Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), beta-blockers (BBK) and mineraloid antagonist (MRA), respectively [1].

Recently, a combined angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhib echocardiogram (Table 2, n=250ition (Sacubitril-Valsartan, ARNI) [2] has demonstrated greater benefit as compared to angiotensin inhibition (Enalapril) improving New York heart association (NYHA) functional class and reducing cardiac mortality in these patients. ARNI decreases the degradation of beneficial natriuretic peptides [3]. Moreover, the PARADIGM-HF trial also found a significant reduction of sudden cardiac death (SCD) by ARNI as compared to ACEI [4]. However, the effect of ARNI in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not described in the PARADIGM-HF trial.

Thus, we prospectively studied patients with rEFHF and NYHA≥II under optimal medical therapy with angiotensin inhibition over 9-month followup and subsequently 9 months after ARNI. The primary objective was to determine the effect of ARNI as compared to angiotensin inhibition in LVEF and left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVDD).

Methods

We prospectively analyzed consecutive rEFHF patients who were referred to our cardiology heart failure/arrhythmia outpatient clinic (n=250). Inclusion criteria were:

1) NYHA functional class ≥ II despite optimal medical therapy, including initiation and titration of ACE inhibitor (ACEI, Ramipril) or Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB, valsartan), beta-blockers (BBK) and mineraloid antagonist (MRA) if tolerance [1].

2) LVEF ≤ 40%;

3) The patient received and tolerated ARNI, which was started in outpatient clinic under stable conditions. LVEF and LVDD were determined in all patients (n=250) every 3 months for a total period of 18 months.

First, patients were observed for 9 months under angiotensin inhibition alone (Ramipril or Valsartan if Ramipril was not tolerated). Then, ACEI (36 hours before) or ARB was stopped and ARNI was initiated and patients were observed for a further period of 9 months under angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition. Patients continued with BBK and MRA.

Oral diuretic use was reduced by half of dosage (i.e., furosemide) at the initiation of ARNI to avoid intolerance due to its potential hypotensive effect. As NYHA functional class improved or remained unchanged, oral diuretic was significantly reduced until interruption if possible. Oral diuretic use was restarted only if NYHA functional class worsened in subsequent clinic visits.

The primary endpoint was to determine LVEF and LVDD under ARNI as compared to angiotensin inhibition.

2D and 3D Echocardiographic parameters

Echocardiogram was performed every 3 months (at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months). LVEF and LVDD was assessed by the biplane Simpson’s method by using two-dimension echocardiogram (2D echo). Echocardiographic contrast was used to enhance border visualization if needed (n=250). Two independent cardiologist reviewed echocardiographic parameters and an interobserver variability was established. In a subset of patients, three-dimension echocardiogram (3D echo) was performed to eliminate interobserver variability, using a previously validated automatic method for LV chamber quantification: heart model® (n=50, using ultrasound Philips® Epic 7) [5-7].

The left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) was calculated by 2D and the LVEDV indexed to body surface area (LVEDV index) was assessed by 3D echocardiogram [8,9]. Operators were blinded to prior LVEF and clinical data. All patient characteristics were taken from outpatient clinic data under stable conditions.

Statistical Analysis

For quantitative and categorical variables, we used the unpaired Student’s t test or the chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test, respectively. Quantitative variables (parametric and non-parametric) were expressed as mean ± standard deviations (SDs) or as mean ± standard error of the mean (SE), respectively. All tests were 2-tailed, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For paired non-parametric quantitative variables, Wilconxon signed-rank test was used. McNemar test was used for paired qualitative variables. Interobserver variability was established by performing intra-class correlation coefficient for quantitative variables (a correlation coefficient≥0.75 is considered excellent agreement). The coefficient of variation from duplicate measurements was also determined. Statistical analysis was performed with statistical software (medcalc®).

Results

Patient characteristics in Angiotensin inhibition group vs. angiotensinneprilysin inhibition group

As shown in Table 1, patients (n=250) averaged an age of 69 ± 8 (76% male) with a mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 31 ± 6 (80% ischemic) and a NYHA of 2.4 ± 0.4. For the first 9 months of follow-up (angiotensin inhibition), patients had an optimal medical therapy, with 100% of patients receiving an ACEI (Ramipril) or ARB (valsartan), 93% a BBK and 83% a MRA.

| Angiotensin inhibition alone | Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition | P-value | |

| (n=250) | (n=250) | ||

| n or Mean ± SD or % | n or Mean ± SD or % | ||

| Follow-up | 9 months | 9 months | |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Age | 69 ± 8 | 70 ± 8 | NS |

| Male (%) | 76% | 76% | NS |

| Ischemic cardiopathy (%) | 80% | 80% | |

| Hypertension (%) | 62% | 62% | |

| Diabetes (%) | 30% | 30% | |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 52% | 63, 52% | |

| Renal insufficiency (%) | 40% | 40% | NS |

| FR <60 ml/min | |||

| Medical treatment | 100% ACE inhibitors or ARB | 100% Sacubitril-Valsartan | |

| Beta-blockers | 93% | 93% | NS |

| Mineraloid antagonist | 83% | 81% | NS |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 9% | 8.50% | NS |

| Oral Diuretic use | 76% | 51% | p<0.03 |

| Rhythm | |||

| Sinus rhythm (%) | 73% | 72% | NS |

| Paroxysmal AF (%) | 13% | 11% | NS |

| Permanent AF (%) | 27% | 29% | NS |

| Clinical data | |||

| NYHA functional class (1-4) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | p<0.0002 |

| Examination data | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122 ± 35 | 108 ± 41 | p<0.02 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74 ± 25 | 63 ± 22 | p<0.006 |

| Heart rate average (bpm) | 67 ± 8 | 64 ± 4 | p<0.006 |

| Blood Test | |||

| Potassium levels | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | p<0.03 |

| Pro-BNP (pg/ml) | 1851 ± 1410 | 1160 ± 815 | p<0.01 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 54 ± 19 | 56 ± 19 | NS |

| Device | |||

| ICD only (%) | 29% | 29% | NS |

| ICD +CRT (%) | 21% | 19% | NS |

| No device (%) | 50% | 52% | NS |

Table 1: Before and after Sacubitril-Valsartan patient characteristics in outpatient clinic.

Then, ACEI or ARB was changed to ARNI in all patients, who were observed for further 9 months (n=250). No significant differences before and after ARNI were observed in the use of BBK or MRA.

Oral diuretic use reduction (i.e., furosemide) was attempted at the initiation of ARNI to avoid intolerance due to its potential hypotensive effect. Consequently, oral diuretic use (i.e., furosemide) significantly was reduced after ARNI, which may be explained by the diuretic effect of ARNI.

ARNI was associated to an improvement in NYHA functional class (p<0.0002) and a decrease of Pro-BNP levels (p<0.01). Glomerular filtration rate was not significantly changed after ARNI. Blood pressure decreased significantly after Sacubitril valsartan. Heart rate decreased also after ARNI (p<0.006).

Improvement of 2D-LVEF and decrease of LVDD after angiotensin inhibition

The interobserver variability analysis (intra-class correlation coefficient=0.95) showed an excellent agreement between 2 observers.

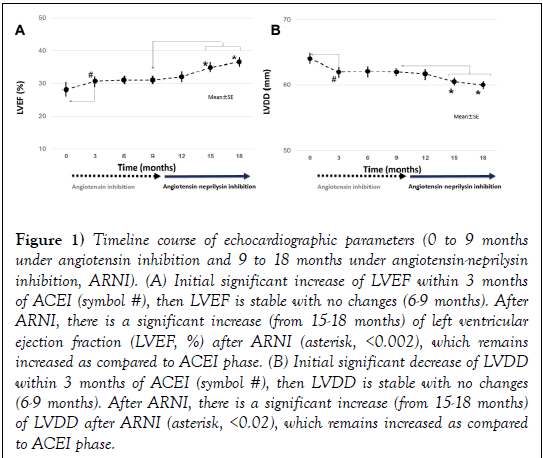

With 2D-echocardiogram (Table 2, n=250), we observed after ARNI an increase of LVEF (from 31 ± 6% to 36.5 ± 8%, p<0.002, Figure 1A) and a decrease in LVDD (from 62 ± 6 mm vs. 60 ± 6 mm, p<0.02, Figure 1B). LVEDV significantly decreased after ARNI (Figure 1C).

Figure 1: Timeline course of echocardiographic parameters (0 to 9 months under angiotensin inhibition and 9 to 18 months under angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition, ARNI). (A) Initial significant increase of LVEF within 3 months of ACEI (symbol #), then LVEF is stable with no changes (6-9 months). After ARNI, there is a significant increase (from 15-18 months) of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) after ARNI (asterisk, <0.002), which remains increased as compared to ACEI phase. (B) Initial significant decrease of LVDD within 3 months of ACEI (symbol #), then LVDD is stable with no changes (6-9 months). After ARNI, there is a significant increase (from 15-18 months) of LVDD after ARNI (asterisk, <0.02), which remains increased as compared to ACEI phase.

| Angiotensin inhibition alone | Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition | P-value | |

| (n=250) | (n=250) | ||

| n or Mean ± SD or % | n or Mean ± SD or % | ||

| 2D-Echocardiogram | |||

| 2D LVEF (%) | 31 ± 6 | 36.5 ± 8 | p<0.002 |

| 2D LVDD (mm) | 62 ± 6 | 60 ± 6 | p<0.02 |

| 2D LVEDV (mL) | 141 ± 17 | 119 ± 15 | p<0.01 |

| 3D-Echocardiogram (n=50) | |||

| Automatic 3D LVEF (%) | 32±4 | 37 ± 8 | p<0.05 |

| Automatic 3D LVEDV index (mL/m2) | 98 ± 7 | 85 ± 8 | p<0.05 |

Table 2: 2D echocardiographic and automatic-3D echocardiographic parameters under angiotensin inhibition vs. angiotensin- neprilysin inhibition

Time course of LVEF and LVDD before and after angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition

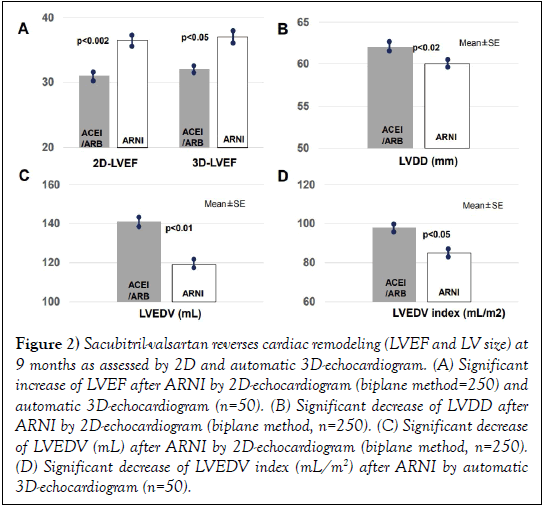

(Figures 2) illustrates the time course of LVEF and LVDD under angiotensin inhibition (0-9 months) and after ARNI (from 9 -18 months).

After 3 months of ACEI/ARB, there was an initial increase of LVEF, maintaining constant values along time from 3-9 months. Then ARNI was started and a further significant increase of LVEF was observed.

Under angiotensin inhibition, the LVDD remained stable. After ARNI, there was a significant decrease of LVDD.

Improvement of LVEF after angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition as determined by automatic 3D-echocardiogram

In a subset of patients, 3D-echocardiogram was also performed before and after ARNI using a fully automatic method (heart model, philips®). This method [5-7] eliminates interobserver variability and exhibits a strong agreement with LVEF assessed by cardiac resonance.

As shown in (Figure 2A and Table 2), a significant decrease of LVEF was also observed after ARNI as performed by automatic 3D-echocardiogram (32 ± 4% to 37 ± 8%, p<0.05). A significant reduction of LVEDV index (Figure 1D) occurred after ARNI as assessed by automatic 3D-echocardiogram.

Figure 2: Sacubitril-valsartan reverses cardiac remodeling (LVEF and LV size) at 9 months as assessed by 2D and automatic 3D-echocardiogram. (A) Significant increase of LVEF after ARNI by 2D-echocardiogram (biplane method=250) and automatic 3D-echocardiogram (n=50). (B) Significant decrease of LVDD after ARNI by 2D-echocardiogram (biplane method, n=250). (C) Significant decrease of LVEDV (mL) after ARNI by 2D-echocardiogram (biplane method, n=250). (D) Significant decrease of LVEDV index (mL/m2) after ARNI by automatic 3D-echocardiogram (n=50).

Discussion

Major findings

The major finding of our study is that Sacubitril-Valsartan (a combined angiotensin and neprilysin inhibition) in rEFHF patients is associated to further reverse of cardiac remodeling, increasing LVEF~5-6% and decreasing LV size (LVDD, LVEDV and LVEDV index). Additionally, Sacubitril- Valsartan was correlated to a significant improve of NYHA functional class.

Therefore, ARNI is associated to improvement of NYHA functional class and LVEF, a marker for SCD.

Sacubitril-Valsartan and cardiac remodeling

Prior studies have shown ACEI/ARB, BBK and MRA reverse cardiac remodeling, increasing LVEF and decreasing LV diastolic size [10,11].

Sacubitril-Valsartan, in addition to angiotensin inhibition, favors an increase of the beneficial natriuretic peptides leading to diuresis, vasodilatation, decrease of sympathetic tone, decrease of aldosterone levels, hemodynamic effects and decrease of fibrosis [3]. Experimental and simulation studies have shown that angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition further suppresses cardiac fibrosis and remodeling as compared to angiotensin inhibition alone [12,13]. The PARADIGM-HF trial demonstrated a decrease of cardiac mortality and sudden cardiac death after ARNI as compared to ACEI [2] Recently, we described a decline in ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate ICD shocks in 120 patients with ICD and rEFHF. In this previously published study, an increase of LVEF was found after ARNI using 2D-echocardiogram [14].

In the present study, Sacubitril-Valsartan was also used according to international guidelines, [2] and we present further evidence with data from a larger sample size (n=250 patients) with and without ICD, using both 2D-echocardiogram and 3D-echocardiogram.

All patients were under an ACEI or ARB, which subsequently was changed to ARNI. Patients received 93% of BBK and MRA in 83% /81% before and after ARNI. Of note, the use of MRA in our study was significantly higher than other relevant trials such as PARADIGM-HF (55%) (2) or DANISH (58%) [15]. Therefore, our population was optimized in terms of medical optimal therapy, which highlights the importance of reversing cardiac remodeling after the addition of Sacubitril-Valsartan.

Additionally, after Sacubitril-Valsartan, patients had a significant improvement of NYHA functional class. The NYHA functional class and LVEF are recognized markers for SCD implicating device implantationdecision making based on international guidelines [16].

LVEF improvement after sacubitril-valsartan in 2D-echocardiogram and 3D-echocardiogram

We detected a significant improvement of LVEF ~5-6% after ARNI by using a quantitative 2D method and an automatic 3D method. Prior studies have demonstrated that 2D-echocardiogram with contrast and 3D-echocardiogram showed a good reproducibility and good agreement with LVEF measured by cardiac resonance [17].

Visual or qualitative assessment of LVEF, even in experience operators, produces an interobserver variability of LVEF~ 5-6%, which is not acceptable for detecting, differences of ≥ 5-10% of LVEF.

Therefore, we used two methods to measure LVEF: 1) Quantitative measurement with 2D-echocardiogram using the Simpson´s biplane method, which may offer smaller interobserver variability (~3-4%) [18-20] and 2) fully automatic 3D-echocardiogram method for chamber quantification (heart model), which eliminates interobserver variability, with a very low test-rest variability [5-7].

Therefore, we believe that the improvement of LVEF after ARNI, documented in our study, is a valuable finding.

Limitations

LVEF after ARNI increased in our study (an absolute value of ~5-6%). In our study, the agreement between observers was excellent in LVEF assessed by the quantitative 2D method (n=250). However, prior studies showed interobserver variability in the quantitative 2D method ranging from 3-7% [18-20] For this reason, we also performed an automatic 3D method, eliminating interobserver variability in a relatively smaller sample size (n=50). Studies with automatic 3D method or cardiac resonance are recommended using larger sample size to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

In a mainly ischemic rEFHF population, angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition further reversed cardiac remodeling, improving LVEF and NYHA functional class, markers for SCD.

REFERENCES

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129-200.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993-1004.

- Hubers SA and Brown NJ. Combined angiotensin receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition. Circulation. 2016;133:1115-24.

- Desai AS, McMurray JJ, Packer M, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-receptor-neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 compared with enalapril on mode of death in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1990-7.

- Medvedofsky D, Mor-Avi V, Amzulescu M, et al. Three-dimensional echocardiographic quantification of the left-heart chambers using an automated adaptive analytics algorithm: Multicentre validation study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017.

- Tsang W, Salgo IS, Medvedofsky D, et al. Transthoracic 3D Echocardiographic Left Heart Chamber Quantification Using an Automated Adaptive Analytics Algorithm. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:769-82.

- Otani K, Nakazono A, Salgo IS, et al. Three-dimensional echocardiographic assessment of left heart chamber size and function with fully automated quantification software in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:955-965.

- Buccheri S, Costanzo L, Tamburino C, et al. Reference values for real time three-dimensional echocardiography-derived left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction: Review and meta-analysis of currently available studies. Echocardiography. 2015;32:1841-50.

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1-39 e14.

- Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569-82.

- Frigerio M, Roubina E. Drugs for left ventricular remodeling in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:10L-18L.

- von Lueder TG, Wang BH, Kompa AR, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 attenuates cardiac remodeling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction by reducing cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:71-8.

- Iborra-Egea O, Galvez-Monton C, Roura S, et al. Mechanisms of action of sacubitril/valsartan on cardiac remodeling: a systems biology approach. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2017;3:12.

- de Diego C, Gonzalez-Torres L, Nunez JM, et al. Effects of angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition compared to angiotensin inhibition on ventricular arrhythmias in reduced ejection fraction patients under continuous remote monitoring of implantable defibrillator devices. Heart Rhythm. 2017.

- Kober L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, et al. Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221-30.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017.

- Wood PW, Choy JB, Nanda NC, et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes: it depends on the imaging method. Echocardiography. 2014;31:87-100.

- Nijland F, Kamp O, Verhorst PM, et al. Early prediction of improvement in ejection fraction after acute myocardial infarction using low dose dobutamine echocardiography. Heart J. 2002;88:592-6.

- Thavendiranathan P, Grant AD, Negishi T, et al. Reproducibility of echocardiographic techniques for sequential assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes: Application to patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:77-84.

- Galderisi M, Henein MY, D'Hooge J, et al. Recommendations of the European Association of Echocardiography: How to use echo-Doppler in clinical trials: different modalities for different purposes. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12:339-53.