Asymmetric sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligament

2 Department of General Surgery, University of Rennes, Renne, France

Received: 06-Oct-2017 Accepted Date: Oct 19, 2017; Published: 26-Oct-2017

Citation: Kieser DC, Leclair SCJ, Gaignard E. Asymmetric sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligament. Int J Anat Var. 2017;10(4):71-2.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Aim: To describe a case of medial asymmetry in the sacrotuberous/sacrospinous ligament complex (SSTL).

Methods: Description of the anatomical findings in a cadaver with an asymmetrical SSTL and comparison to five anatomically normal cadaveric dissections.

Results: Marked asymmetry with an atypical proximal origin and cord-like SSTL is described and contrasted to the more typical fan-shaped ligament complex. No vascular perforators traversed the SSTL in the atypical case and the vessels were relatively protected during SSTL release.

Conclusion: Significance variance and asymmetry within the SSTL can occur. Surgeons should be aware of this phenomenon and consider anatomical variations when performing a peri-sacral dissection.

Keywords

Sacrotuberous; Sacrospinous; Ischial spine

Introduction

Posterior approaches to the sacral and peri-sacral region pose a challenging surgical problem due to their relative rareness and complex regional anatomy [1]. Multiple surgical techniques have been described, but often need to be modified to account for the specific patient and pathology being treated [1-4].

The “sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligament complex” (SSTL) usually acts as a reliable landmark as to the depth of surgical dissection. It also acts as a barrier to inadvertent injury of anterior structures, notably the gluteal vessels, which may pose life-threatening haemorrhage if damaged [5-7].

The sacrospinous ligament is a triangular shaped structure that originates from the anterior sacrum and coccyx and inserts on the ischial spine [8]. Medially, its fibers are intermingled with the more posterior fan-like sacrotuberous ligament, which takes origin from the sacrum, coccyx, ilium and sacroiliac joint capsule and inserts on the ischial tuberosity [8,9]. As the fibers of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments are conjoined medially, this region is more appropriately clinically defined as the sacrospinous/sacrotuberous ligament complex (SSTL).

To our knowledge, there are no previous publications describing atypia or asymmetry in the origin and peri-sacral region of the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligament. However, any atypia or asymmetry could risk anterior structure injury, particularly if the position of the SSTL on one side is relied upon as the approximate position on the contra-lateral side. Furthermore, with the advent of less invasive procedures, particularly minimizing lateral dissection during sacrectomy, an accurate understanding of the origin of the SSTL is necessary.

Thus, this study aims to describe a case of an atypical, asymmetrical SSTL and compare it to the normal anatomy, in an attempt to provide surgeons with an awareness of this phenomenon and hopefully prevent inadvertent peri-sacral injury.

Methods

Six fresh human cadavers (3 male, 3 female, and age range 80-101 years) were utilized. One case, an 87-year-old male with an atypical, asymmetrical SSTL, was compared to the remaining five cadavers. All cadavers were positioned prone in the anatomical position and a posterior dissection of the sacrum and SSTL performed through a direct midline incision as would be utilized during posterior sacrectomy.

The gluteus maximus, which arises from the posterior sacrum, SSTL and iliac crest, was elevated from medial to lateral to expose the SSTL. The SSTL origin was then analyzed for its position on the sacrum. Subsequently, the SSTL was longitudinally incised 1 cm lateral to the lateral margin of the sacrum to determine its thickness and proximity to the “Superior Gluteal Artery” (SGA) and “Inferior Gluteal Artery” (IGA).

Results

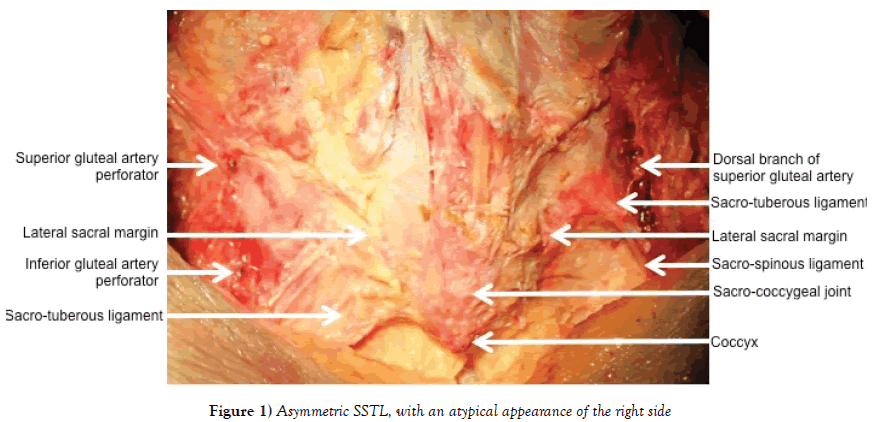

Of the six cadavers, only one displayed SSTL origin asymmetry. In this case the left side showed consistent anatomy with the other five cadavers with a broad fan-like sacrotuberous ligament originating 33 mm proximal to the Posterior-inferior Sacroiliac Joint (PISIJ) (average 38 mm, range 29-38 mm), just distal to the S2 foramen, and extending to the upper portion of the coccyx. The sacrospinous ligament was similarly positioned and took origin from S2-S4.

In contrast, the right side was more cord-like with a sacrotuberous ligament that originated 56 mm proximal to the PISIJ, just distal to the S1 foramen, and extending to the mid portion of S4. The sacrospinous ligament originated from S2-S3.

More laterally, the left SSTL maintained a typical broad fan shaped appearance, whereas the right side merged towards a central narrow ligament complex 10 mm lateral to the lateral sacral margin (Figure 1).

In all cases the sacrospinous ligament inserted on the ischial spine and the sacrotuberous ligament inserted into the ischial tuberosity. Gluteus maximus, even in the atypical case, gained partial origin from the sacrotuberous ligament.

The SSTL thickness 10 mm lateral to the lateral margin of the sacrum (antero-posterior dimension), was similar between the typical and atypical pattern (5 mm and 6 mm respectively). For the symmetrical cases the thickness was an average of 5.5 mm (range 4-6 mm). An anatomical plane was clearly identified anterior to all ligament complexes and posterior to the piriformis and coccygeus muscles.

The SGA and IGA were expectantly found to course along the superior and inferior surface of the piriformis muscle respectively, in all cadavers. Branches of the SGA and IGA were also found to perforate the SSTL in all samples, except the right side of the asymmetric case where no perforators were identified. In this case a dorsal branch of the SGA emerged superior to the SSTL 3 cm lateral to the lateral sacrum and coursed laterally along its superior margin. Because the SGA and IGA originate more anteriorly from the internal iliac artery, their course is relatively more anterior the more medial the dissection. The distance of the SGA from the SSTL 10 mm lateral to the lateral sacrum, at the level of the SSTL incision, was 15 mm on the left and 17 mm on the right for the asymmetric case and similar for all other cases (average 15 mm, range 14-17 mm). At the level of the lateral sacrum the distance was 20 mm on the left and 22 mm on the right (average 19 mm, range 18-22 mm).

For the IGA the distance from the SSTL 10 mm lateral to the lateral sacrum were 13 mm on the left and 15 mm on the right for the asymmetric case and similar for all other cases (average 15 mm, range 12-17 mm). At the level of the lateral sacrum the distance was 40 mm on the left and 38 mm on the right. This was higher than the other cases, which averaged 29 mm (range 20-35 mm).

Discussion and Conclusion

Peri-sacral surgery is challenging, particularly identifying and protecting anterior structures from a posterior approach [1]. Wide dissection was historically utilized to aid identification of anatomical structures, but causes significant soft tissue disruption. Thus, more recently, less invasive techniques have been favored when the pathology permits. These techniques limit lateral dissection or utilize percutaneous methods to release the SSTL from the sacrum. The SSTL is then gently retracted laterally to prevent vascular perforator injury and minimize soft tissue trauma.

Irrespective of the type of surgery, in a posterior approach the SSTL acts as a useful landmark to the depth of dissection and its origin is relied upon to prevent plunging into anterior structures, notably the gluteal vessels. This study illustrates that significant variance of the SSTL can occur, even within the same patient. Unfortunately, this study is not powered to identify the rates of SSTL atypia or to classify such variances. Instead, it aims to draw awareness of potential anatomical variances of the SSTL and asymmetry within an individual patient.

Previous authors have described variances in the more lateral sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments as well as vascular perforation variances [8,10]. However, peri-sacral surgery relies on an understanding of the origin and medial aspects of the SSTL. Despite this, no prior literature exists on the variances of the medial SSTL and SSTL origin. Yet, this is of particular importance for surgeons performing peri-sacral surgery, especially if less invasive or percutaneous approaches are to be utilized.

Interestingly, the atypical right SSTL in our case had no vascular perforators present and the vascular structures were more anterior than in the symmetrical cases. This suggests that despite this variation vascular injury would have been unlikely during the release of the SSTL. However, because the SSTL typically covers the anterior structures and offers protection from inadvertent injury, surgeons often dissect directly onto this structure. In this case, surgical dissection to identify a typical large fan-like SSTL may have resulted in the surgeon plunging superior or inferior to the cord-like SSTL and thus risk anterior structure injury.

In conclusion, this study illustrates that significant variance in the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligament complex can occur. Furthermore, asymmetry within an individual patient may occur. Surgeons should be aware of atypical intra-operative appearances and consider anatomical variations if abnormalities are encountered.

Acknowledgements

Glynny Kieser for her editorial input.

REFERENCES

- Karakousis C, Sugarbaker PH. Sacrectomy. In: Malawer MM, Sugarbaker PH (eds.) Musculoskeletal Cancer Surgery. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 2001;415-24.

- Zhang HY, Thongtrangan I, Balabhadra RSV, et al. Surgical techniques for total sacrectomy and spinopelvic reconstruction. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:1-10.

- Randall RL, Bruckner J, Lloyd C, et al. Sacral resection and reconstruction for tumour and tumour-like conditions. Orthopaedics. 2005;28:307-13.

- Tomita K, Tsuchiya H, Kawahara N, et al. En bloc sacrectomy. In: Watkins RG and Watkins RG (eds.) Surgical Approaches to the Spine. Springer. 2015;245-50.

- Lim EVA, Lavadia WT, Roberts JM. Superior gluteal artery injury during iliac grafting for spinal fusion: A case report and literature review. Spine. 1996;21:2376-8.

- Altman DT, Jones CB, Routt ML. Superior gluteal artery injury during iliosacral screw placement. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:220-2.

- Belley G, Gallix BP, Derossis AM, et al. Profound hypotension in blunt trauma associated with superior gluteal artery rupture without pelvic fracture. J Trauma. 1997;43:703-5.

- Hammer N, Steinke H, Slowik V, et al. The sacrotuberous and the sacrospinous ligament-a virtual reconstruction. Ann Anat. 2009;191:417-25.

- Loukas M, Louis RG, Hallner B, et al. Anatomical and surgical considerations of the sacrotuberous ligament and its relevance in pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28:163-9.

- Lai J, Du Plessis M, Wooten C, et al. The blood supply to the sacrotuberous ligament. Surg Radiol Anat. 2017;7.