Boys with Gender Identity Disorder: A Follow-Up Study

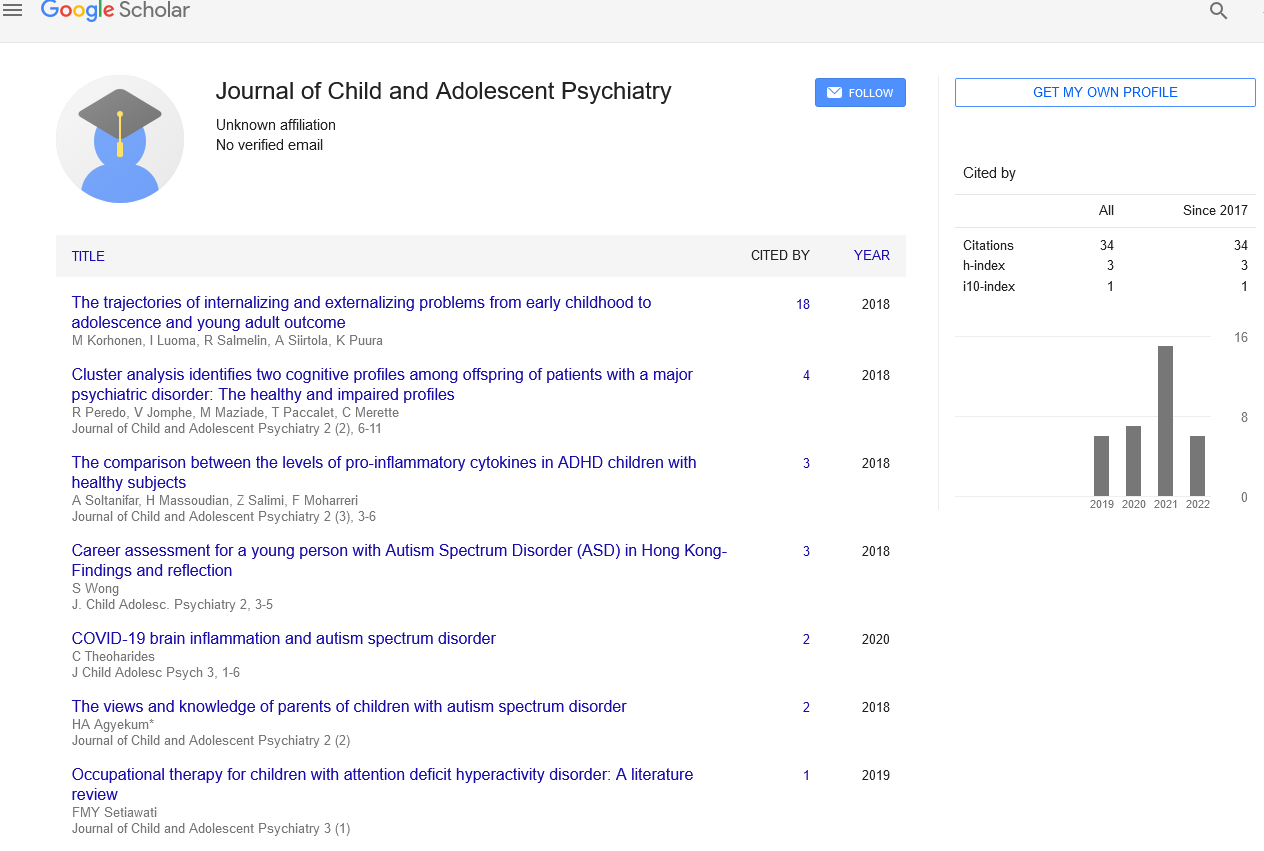

Received: 04-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5435; Editor assigned: 12-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. PULJCAP-22-5435(PQ); Accepted Date: Aug 31, 2022; Reviewed: 16-Aug-2022 QC No. PULJCAP-22-5435(Q); Revised: 04-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5435(R); Published: 04-Sep-2022, DOI: 10.37532/puljcap.2022.6(5);30-31.

Citation: James S. Boys with gender identity disorder: A follow-up study. J Child Adolescence Psychiatry. 2022; 6(5):31-32.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

This study presents follow-up information on gender identity and sexual orientation for the largest group of boys clinic-referred for gender dysphoria (n=139). The boys were first evaluated when they were children, when they were a mean age of 7.49 years (range, 3.33–12.99), in a mean year of 1989, and then they were reassessed when they were a mean age of 20.58 years (range, 13.07–39.15), in a mean year of 2002. In terms of gender identity disorder in childhood, 88 (63.3%) of the males satisfied the DSM-III, III-R, or IV criteria, while the remainder, 51 (36.7%), fell below the threshold. At the follow-up, participants' gender identity/dysphoria was evaluated using a variety of techniques, and they were divided into persisters and desisters. Both fantasy and behaviour were assessed for sexual orientation, which was then classified as either biphilic/androphilic or gynephilic. Of the 139 participants, 17 (12.2%) fell into the persisters category, whereas 122 (87.8%) fell into the desisters category. For 129 participants, information on sexual orientation in fantasies was provided; 82 (63.6%) were classified as biphilic/androphilic, 43 (33.3%) as gynephilic, and 4 (3.1%) reported no sexual fantasies. Data on 108 participants' sexual orientation and behavioural data were available. Of these, 51 (47.2%) were classified as biphilic/androphilic, 29 (26.9%) as gynephilic, and 28 (25.9%) as having no sexual behaviour. With the biphilic/androphilic desisters serving as the reference group, multinomial logistic regression looked at predictors of outcome for the biphilic/androphilic persisters and the gynephilic desisters. The biphilic/androphilic persisters had more gender-variant scores on a dimensional composite of sex-typed behaviour in childhood than the reference group did, and they tended to be older at the time of evaluation in childhood. In comparison to gynephilic desisters, biphilic/androphilic desisters were more gender-variant. Boys who had been referred to a clinic as children for help with gender identity issues showed significant rates of desistance and biphilic/androphilic sexual orientation. The data's implications for the way that children with gender dysphoria are currently treated are examined.

Introduction

For the majority of individuals, one's sense of self is thought to be largely shaped by their gender identification. Although cognitivedevelopmental gender theory contends that understanding of gender as an "invariant" aspect of the self does not happen until early to middle childhood, with the achievement of creative operational thought, most kids can self-label themselves as either a boy or a girl by the age of three, if not earlier. Even in the preschool years, if not earlier, gender disparities in the adoption of gender role behaviour connected to societal notions of masculinity and femininity—appear. These actions cover a range of areas, such as peer, toy, role-playing, and activity preferences. Long-standing normative developmental research has shown that there are large and substantial between-sex disparities in both gender identity and gender role behaviours. Later in development, sexual orientation also reveals a significant asymmetry between the sexes, with most men sexually attracted to women and most women to men.

A tiny body of clinical literature developed in the 1950s and 1960s to describe the phenomenology of kids who exhibited clear gendervariant behaviour, including a strong desire to be the other gender. Additional volumes by Stoller and Green give more in-depth accounts of these kids. These early studies followed the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders' addition of the diagnostic term Gender Identity Disorder (GID) of Childhood, which is now known as Gender Dysphoria (GD) in the DSM-5. Since 1980, empirical research has looked at a variety of aspects of GID/GD, including epidemiology, methods for diagnosis and evaluation, related psychopathology, causal mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies.

The present study's focus is on another parameter, which is the development of GID in children. Early research suggested that pervasive gender-variant behaviour in children might be a predictor of GID in adults. At the same time, it was acknowledged that gendervariant behaviour in childhood was associated with sexual orientation (in males, androphilic, which is defined as a sexual attraction to men; in females, gynephilic, which is defined as a sexual attraction to women) but not with concurrent gender dysphoria. Children whose conduct was in line with the DSM diagnosis of GID (or GD following DSM-5) had undergone at least 10 follow-up studies as of this writing. The first evaluation in childhood occurred between 1952 (49) and 2008 across these studies. The sample sizes for the 9 studies that included boys ranged from 6 to 79 (excluding those lost to follow-up). In the majority of these investigations, the age at the time of the initial evaluation during childhood was also recorded. This age ranged from 4 years to 12 years, with a mean between 7 years and 9 years and a standard deviation of 0.48.

13 (34.2%) of the 53 boys in the small sample size studies were classified as gynephilic, while 25 (65.8%) were classified as biphilic/androphilic. The remaining 15 patients (28.3% of the combined samples) had sexual orientations that were either uncertain or unknown.

or unknown. 33 (75%) of the boys in Green's study were classified as biphilic or androphilic in fantasy, while 11 (25%) of the boys were classified as gynephilic (Kinsey scores of 0, 1). (Kinsey ratings of 2–6). In terms of behaviour, 6 (20%) people were categorised as gynephilic, and 24 (80.0%) as biphilic/androphilic. Because they had no interpersonal sexual experiences, the other 14 males (or 31.8% of the sample as a whole) could not be categorised in terms of conduct. In Green's study, a comparison group of males drawn from the community who had their sexual orientation tested revealed that 100% of them (n= 35) were categorised as gynephilic in fantasy and 96% (n=25) as gynephilic in behaviour.

Keywords

Functional motion disorders