Care of linguistic minorities in the pediatric population: challenges

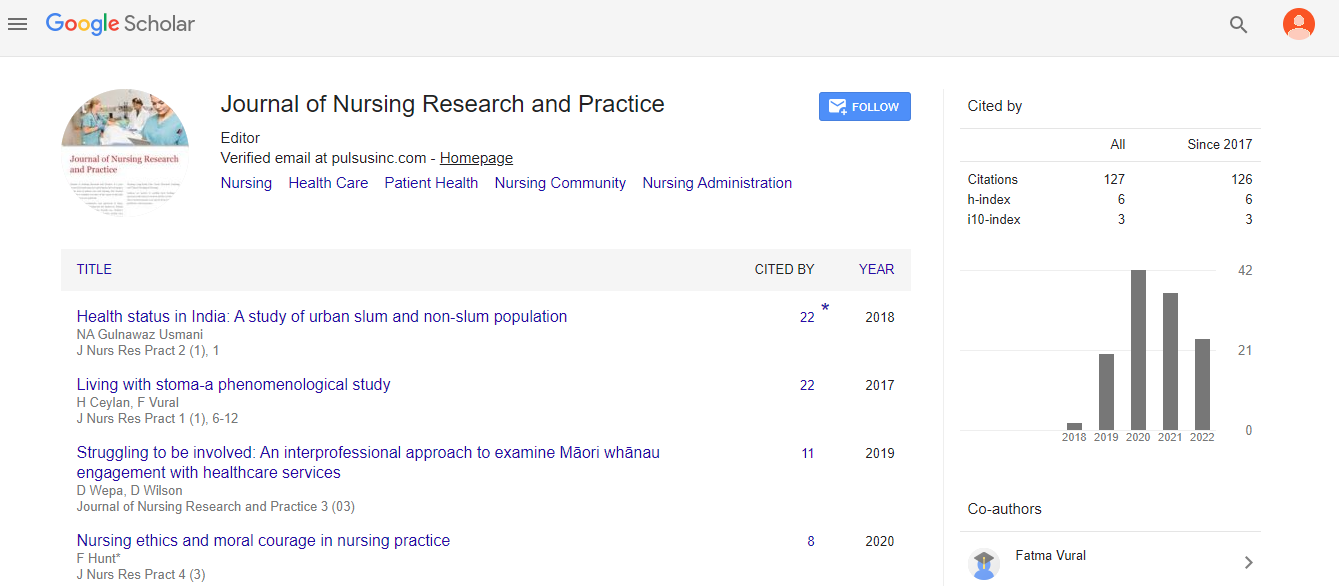

Received: 15-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5625; Editor assigned: 16-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. PULJNRP-22-5625(QC); Accepted Date: Nov 25, 2022; Reviewed: 19-Nov-2022 QC No. PULJNRP-22-5625(Q); Revised: 24-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5625(R); Published: 27-Dec-2022, DOI: DOI: 10.37532/Puljnrp -.22.6(9).152-154.

Citation: Michael J. Care of linguistic minorities in the pediatric population: Challenges. J Nurs Res Pract. 2022; 6(9):152-154

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

When treating patients with limited English proficiency, particularly those who speak unusual languages, doctors in the United States encounter a variety of specific challenges. Speaking Mayan dialects is increasingly underrepresented in detention facilities and immigration courts on the U.S.-Mexico border. This issue is not limited to the delivery of health treatment. In the case of insufficient translator services, parent-child dynamics and other important information pertaining to paediatric treatment may be lost in translation. Different approaches could be used to alleviate the discrepancies in medical treatment experienced by people with LEP who speak both rare and more widely spoken languages. These include expanding and rewarding training programmes for professional interpreters, giving medical students specialized instruction in interpreter services, and standardizing interpretation services offered by regional consulates and nonprofit organizations for both medical and legal purposes.

Opinion

he foundations of a long history of immigration lay the groundwork for the current population of the United States. Despite the fact that English is still spoken informally, the U.S. Census estimates that 21.6% of people aged 5 and over speak another language at home. Federal agencies were required to enhance their systems and programmes for people with Limited English Proficiency by an executive order issued in 2000 and 2003, the Department of Health and Human Service produced instructions on how to implement the order. Health care organizations have to "take reasonable steps to ensure meaningful access to each individual with limited English proficiency eligible to be served or likely to encounter in its health programmes and activities, according to the Hhs. There are no federal regulations mandating trained or licensed interpreters, claim Jacobs, Hhs does advocate the employment of licensed medical interpreters, while it is not required. The National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters and the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters are the two accrediting organizations in the United States that offer certification for medical interpreters. However, in tiny clinics that essentially run as companies, interpretation is expensive and occasionally challenging to accomplish. However, a number of state-run variations of our federal insurance programme will reimburse medical/interpreting services. Despite the fact that this clause basically relates to all interpretation, we came across two instances where the system in place for matching patients with qualified interpreters fell short. While pantomiming or using ad hoc translators in a hectic teaching environment may be alluring, one meta-analysis revealed that the quality of treatment for patients with limited English proficiency is inferior when such untrained interpreters are used. Errors in medical interpretation brought on by a patient's native language proficiency frequently have clinical repercussions. Even Spanish-speaking patients in the US have been discovered to receive inferior care and shorter clinical encounters compared to native English speakers. However, patients in facilities that receive government funds are legally required to have access to language services free of charge. The first case we came across included a problem with caring for a speaker of an uncommon language despite having a somewhat effective interpretation service programme in place, as detailed by L.D. The second scenario sheds light on a standard procedure used by healthcare professionals when dealing with language barriers in a resource-constrained environment outside of the United States.

Lack of Expert Interpreters for Rare Languages

As a third-year medical student, I was administering immunizations at a mobile children's clinic that provides care to kids who frequently had little insurance or none at all. The majority of these individuals were covered by Medicaid, a federal-state insurance programme that covers medical expenses for low-income people. Numerous patients in our mobile clinic were also recent arrivals to the country who spoke little or no English. This was the situation when a young Guatemalan boy came to the clinic with his father, who spoke their primary language, a rare Mayan dialect, and very basic Spanish. Our medical staff struggled even more to resolve the child's primary headache complaint as a result of this issue. I was sure that I could quickly arrange for a Spanish interpreter to arrive at a patient's bedside, either in person or over the phone, thanks to my extensive rotations in our county hospital. Medical interpreters in uncommon languages are more challenging to locate, nevertheless. It is frequently necessary to make an appointment weeks in advance. The father's shaky Spanish was used by our team as a last resort, and it was translated into English via an on-demand Spanish phone interpreter. I did, however, sense some unease in the boy's responses to our probing queries, such as whether he had witnessed anything alarming while travelling. Was he content with the meals his father could provide. When our inquiries were translated from English to Spanish, it also became clear that the father didn’t understand all of them. My attending physician determined that the primary goal of this examination should be to look for headache symptoms that could be warning signs of intracranial pathology. We felt confident enough in our interview findings to conclude that the youngster was not awakened from sleep by the headaches, they were not occipital in origin, and they were not followed by nausea, vomiting, or ataxia. We also performed a neurological examination, which demonstrated the lack of nuchal rigidity, papilledema, and focal weakness. In the end, my attending doctor agreed to arrange for an interpreter in their native tongue and reevaluate the case at a follow-up appointment in two weeks. When I left the clinic that day, I pondered what might be causing the child's misery. Could we have made the correct diagnosis if we had been more proficient in his mother language? I recently had a conversation with the father and his son, and as a result, I became aware of the challenges of caregiving for people who don't speak English very well in my own nation. Health care delivery is not the only area where people lack professional resources; at our southern border, Mayan dialect speakers also have a decreasingly small representation in immigration courts and detention facilities.

Risks associated with using medical information for telephone games

I arrived in a situation where there were no qualified interpreters because I was a resident in internal medicine and paediatric rotating at a teaching hospital in Kenya. Five patients and their moms were crammed into the failure-to-thrive room, which was no larger than a closet. My team was rounding there. We detected a child with visceral leishmaniasis during rounds, but his mother could only communicate in a certain tribal language. Fortunately, another mother in the space spoke this language as well, and we discovered a nursing student who spoke Swahili in addition to the main tribal language of the second mother. The group eventually translated my English into Swahili before translating it into both tribal tongues. I condensed the message to the diagnosis, its mechanism of transmission, the prognosis, and the recommended course of action because I was aware of the possible dangers of playing telephone with medical information. Eventually, the mother nodded, realizing that her kid would probably make a full recovery, provided that he could continue to get antibiotics in the hospital for an additional three weeks.

Alternatives to address care gaps for Americans with limited english proficiency

Although not ideal, exchanges like these could help patients in a context with inadequate resources avoid the consequences of having little understanding. However, in the United States, both speakers of rare languages and those who speak Spanish struggle to find trained translators due to ingrained structural and psychological hurdles. Our nation currently does not have a necessary standardized education and certification programme for medical interpreters, which raises the risk of avoidable medical mistakes in the treatment of such patients. Despite the fact that many medical students are surrounded by people who do not speak English during clinical rotations, the demands of medical school offer little time for them to become fluent in another language. There is a lot of education in medical schools about the necessity of using a skilled interpreter at all times, but there are rarely in-depth conversations about how to support linguistic minorities. As we have learned, when playing games of medical telephone, important parent-child dynamics as well as patient-provider rapport may also be lost in translation. The discrepancies in treatment that patients and parents with LEP experience can be addressed in a number of different ways. It is crucial to increase the number and accessibility of qualified translators in order to reduce clinical effects for such minorities. According to one study, mandating at least 100 hours of training for interpreters will probably greatly reduce medical interpretation errors. In our personal experience, we noticed that patients generally appeared happier when speaking to an interpreter present via videoconference as opposed to telephone, a finding that was reflected in a prior study. Focused education probably results in earlier proficiency compared to those who receive no training in terms of medical students' ability to use the available interpreter services. It may be helpful to prepare for real-life situations by including translator challenges in patient simulations during medical training, especially in paediatric encounters where both the patient's and the guardian's perspectives must be taken into account. Outsourcing hospital-based medical interpretation to call centres in other nations may be a crucial tactic to provide access regardless of the patient's location, especially for rare languages. A more practical approach, though, might be to tackle issues with both our legal and health care systems at once. The number of trained interpreters might be increased by expanding Mayan-language interpreter training programmes at a time when demand is anticipated to rise in immigration courts, safety net clinics, and other community settings. Unifying the medical and legal interpreting services offered by regional consulates and charitable organizations could guarantee that speakers of rare Central American languages receive proper representation. Pediatricians-in-training should be aware that interpreting challenges can make it more difficult to sort through the already complicated interactions between the patient and guardian. We were prepared for the chance that the youngster wouldn't want to say he was hungry or thirsty in front of his father during our patient interaction at the mobile clinic. In these kinds of situations, having an interpreter available who speaks the patient's primary language is even more crucial. If this is not possible, then the chief complaint's lifethreatening causes should be ruled out while making arrangements for a suitable follow-up with a qualified interpreter.Medical students would be better prepared to advocate for these patients in the future if they were made aware of the breadth of difficulties faced by linguistic minorities through clinical exposure, didactics from professional interpreters, and patient simulators. In addition to mandating a uniform certification procedure for interpreters, regional and national organizations must to introduce incentives for employment in the sector. With this dual strategy, paediatric patients would be guaranteed a voice in the increasingly globalized world.