Diagnostic and therapeutic delays in heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients

Received: 03-May-2022, Manuscript No. puljp-22-5967 ; Editor assigned: 06-May-2022, Pre QC No. puljp-22-5967 (PQ); Accepted Date: May 26, 2022; Reviewed: 18-May-2022 QC No. puljp-22-5967 (Q); Revised: 24-May-2022, Manuscript No. puljp-22-5967 (R); Published: 30-May-2022

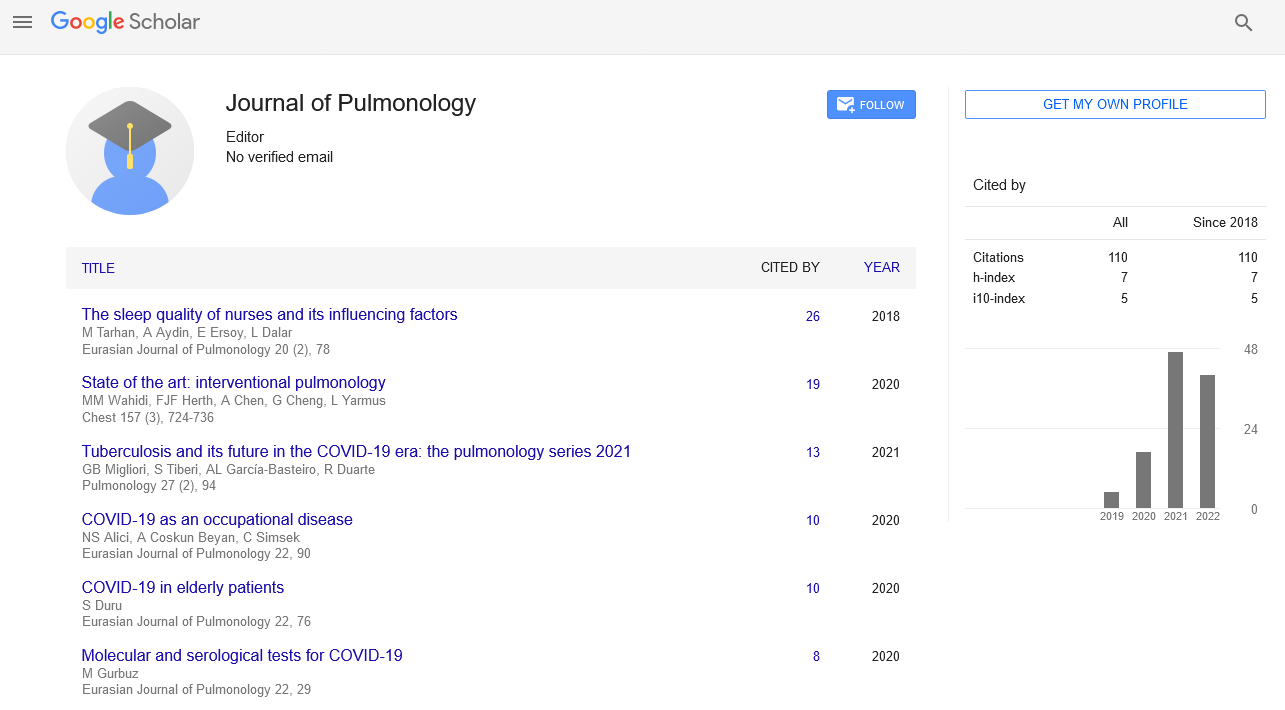

Citation: Verma K. Diagnostic and therapeutic delays in heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J. Pulmonol .2022; 6(3):35-37.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Many patients have both Heart Failure (HF) and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Recent population-based registries indicate that spirometry is commonly not used to diagnosis concomitant COPD in patients with Heart Failure (HF) and that individuals with COPD frequently do not receive the advised Beta-Blocker (BB) medication. This cutting-edge review covers current issues with underusing and underdoing BBs in patients with HF and COPD despite guidelines' recommendations, as well as difficulties in applying advised spirometry for COPD diagnosis in patients with HF. The use of the nonselective BB carvedilol, target BB doses in patients with HF and COPD, BB and bronchodilator management during HF hospitalization with and without COPD exacerbation, and the use of BBs in COPD patients with right HF or free from cardiovascular disease are all open issues in the therapeutic management of patients with HF and COPD that are discussed in the third section. The entire case study presented here argues in favor of a bipartisan endeavor to draw immediate attention to the implementation of clinical practice recommendations from guidelines for patients with HF and co-occurring COPD.

Keywords

Screening; Undernutrition; Pleural disease; Interventional pulmonology

Introduction

There has been a great deal of research on the coexistence of Heart Failure (HF) and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). It has been demonstrated that around of patients with HF also have COPD, and a similar frequency of HF in sizable populations of COPD patients has also been found. The prognosis impact of this confluence of chronic illnesses appears negative. As a matter of fact, COPD has been independently linked to an increase in hospitalizations and mortality among individuals with chronic heart failure. The fundamental causes of the correlation between these illnesses have not been fully analyzed and are up for discussion. Along with common causes like ageing and leading an unhealthy lifestyle, both problems may be caused by the persistent inflammatory burden that COPD adds to the heart failure syndrome. This could exacerbate heart illness and patients' functional status while also promoting atherosclerosis and upsetting the vascular system's hemodynamic state. Another fascinating idea is that these relationships may be mediated by COPD patients' underuse of HF medicines. The underuse and underdoing of Beta-Blockers (BBs), in particular, has been shown in patients with HF and COPD and may be a factor in rising hospitalization and mortality rates. The use of nonselective versus selective (so-called cardio selective) BBs in patients with COPD and their correct dose in patients with acute and chronic HF have both come under scrutiny. In this regard, the application of pulmonary function tests (especially spirometry) in patients with HF would enable the development of a firm diagnosis of chronic airflow limitation and therapy with bronchodilator medications when appropriate. As a wider spectrum of phenotypes within the HF syndrome have been recognized, the HF situation has grown increasingly complex. The care of patients with co-occurring COPD is complicated by the rising prevalence of HF with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, for which specific pharmacological recommendations in guidelines have not yet been found and are sparse. The potential benefits of BB medicines in patients with COPD are also supported by growing evidence in the field of respiratory medicine, regardless of the presence of cardiovascular disorders for which they are recommended. In this review, we emphasize unanswered questions in the therapeutic management of these patients, gains in understanding, and areas of prospective improvement with an emphasis on existing diagnostic and therapeutic gaps in the use of spirometry and BBs in patients with HF and COPD. Most of the information on COPD's prevalence and prognostic effects that has been gathered so far from big HF registries is of uncertain quality. They are mostly obtained "from a check box on a case report form," which is often assigned based on the enrolling investigator's own clinical opinion after taking into account the patient’s medical histories, findings from physical examinations, smoking behaviors, and bronchodilator medication. Spirometry is, in fact, not commonly taken into account in patients with HF and known or suspected COPD, despite the fact that it is recommended in pulmonology recommendations for the diagnosis of COPD.

Only ambulatory individuals with HF and physician-reported COPD who were registered in a recent large multinational European registry had access to spirometry. Recent HF guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology seem to support a pragmatic approach to COPD diagnosis, stating that "Both correctly and incorrectly labeled COPD is associated with worse functional status and a worse prognosis in HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction." The discriminatory capacity of spirometry in patients with HF is perceived by the cardiology community as uncertain. A similar number of patients with chronic HF have unrecognized airflow obstruction, according to estimates, but due to the infrequent use of spirometry, approximately of those with chronic HF are mistakenly diagnosed with COPD without having proven airflow obstruction. So there is good justification for promoting spirometry use in cardiac clinics for HF. It can be difficult to differentiate between COPD and HF in individuals who also have other risk factors, such as smoking, inactivity, or advanced age. Both disorders have symptoms like weariness, persistent dyspnea, and reduced exercise tolerance. Obstructive post-bronchodilator spirometry can be used to confirm the diagnosis of COPD in symptomatic adults with typical clinical characteristics. Demonstrates a useful flowchart for spirometry test interpretation. The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease recommended using a defined cutoff for the ratio of postbronchodilator forced expiratory, diagnosing persistent airflow restriction, and using the percentage of projected FEV1 to further stratify the obstruction's severity. Although using the LLN may be more accurate, subjects classified as normal using the LLN but abnormal using the fixed ratio were found to have an increased risk of hospitalization and mortality, suggesting that elderly patients who may have been overdiagnosed may be more likely to experience negative outcomes. The international strategy paper for COPD recommends using the fixed ratio instead of the LLN since it is easier to use and more reliable. Following that, symptoms and exacerbation risk are evaluated in patients with HF with persistent airflow limitation. With main bronchodilators, this classification defines the initial course of medication. Step-up therapy, such as inhaled corticosteroids, are suggested for patients whose condition is not sufficiently under control. This journal has recently published comprehensive directions for spirometry. Spirometry's applicability, interpretation, or effectiveness in patients with heart failure and low left ventricular ejection fraction have not been found to differ significantly, according to reports to far. The final common pathway underlying the emergence of respiratory symptoms in both illnesses is lung congestion. It might be challenging to interpret the results of a lung function test when it occurs during periods of left cardiac decompensation and fluid overload due to typical alterations in the test's findings. Spirometry should ideally be performed in a compensated state to minimize misdiagnosis, despite the fact that there are no specific recommendations about its execution in patients with HF. Patients may also exhibit obstruction of the small airways in isolated right HF caused by idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, which can be challenging to distinguish from obstructive lung disease. These disorders may be distinguished by additional testing, particularly Doppler echocardiography, highresolution computed tomography of the lungs, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Another clinical problem is telling COPD from asthma. Respiratory symptoms brought on by restricted airflow, which often change over time, are what are known as asthma symptoms. Testing for the reversibility of bronchodilator effects or other tests can provide evidence of the variability in lung function. When the patient used a bronchodilator before the test or during exacerbations, reversibility might not be present. Bronchodilator reversibility, though traditionally used to distinguish between asthma and COPD, is also frequent in COPD, is not a stable characteristic, and does not predict a patient's long-term response to maintenance bronchodilator medication. Reversibility tests cannot, therefore, be used to distinguish between COPD and asthma. Alternately, people with varying respiratory symptoms may be diagnosed with asthma using bronchial provocation testing to measure airway hyper responsiveness and long-term follow-up of lung function. Patients with COPD had significantly lower carbon monoxide diffusion capacity than asthma patients, which could be used to distinguish between the two conditions. The issue about the distinction between BB use and dose in randomized controlled trials versus observational studies may be influenced by various comorbidities that cluster with COPD, particularly within the phenotype, in addition to the increased prevalence of COPD in real-world HF populations. There are still significant information gaps in the care of this population. Preliminary studies have produced conflicting results and in-depth research of the difference in COPD prevalence and prognostic impact in patients with versus those insufficient. But even though BB therapy is officially indicated for patients with concurrent cardiovascular problems such as atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, BBs are still currently not advised for usage in patients. It is up for debate and needs more research on whether BB target doses should vary across people with and without COPD, as well as with the escalating severity of COPD. The question of whether the therapeutic goal of BB therapy in patients with HF in sinus rhythm should be achieving the target doses advised by recommendations or a target Heart Rate (HR), beats/min, is also still up for dispute, regardless of the presence of COPD. Reaching goal doses of BB (especially in conjunction with reaching target doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers) was linked to better outcomes in the European registry. A post hoc analysis of the HF-ACTION experiment confirmed this finding, showing that a greater BB dose rather than a more lowered HR was related with improved outcomes In contrast, the size of the HR drop but not the BB dose was related to the survival benefit in a meta-analysis of HF studies. These findings imply that it is fair to take into account both the target resting HR and the greatest tolerated BB dose. The idea of a "target effect" as opposed to a "target dose" may provide doctors more assurance when administering BB. If the goal HR cannot be safely obtained by BB titration in individuals with symptomatic COPD, ivabradine can be added. These drugs work in concert to dilate the airways and do so via several methods. It is well known that these medications are effective at reducing COPD exacerbations and improving exercise tolerance, lung function, and quality of life. Long-acting bronchodilators have been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in a number of observational studies and a meta-analysis, but this was not confirmed in randomized controlled trials, from which patients with significant cardiovascular disease, particularly symptomatic HF, are typically excluded. Therefore, the relationship between long-acting bronchodilators and symptomatic HF is still up for debate. A primary care research database found that using long-acting bronchodilators concurrently increased the risk of heart failure (HF), however, there are little and conflicting data on the safety of doing so in patients with known HF and COPD. The use of short-acting b2-agonists was linked to a higher risk of HF hospitalization and all-cause mortality in a cohort of patients. The Central Illustration suggests a streamlined treatment schematization. During HF hospitalizations, diuretic medication is the mainstay treatment for reducing lung and peripheral congestion; inotropic drugs are linked to the existence of pump failure and hypo perfusion. To determine the best treatments, a thorough workup should always make an effort to address any suspected cardiovascular causes of HF hospitalizations, which account for nearly half of cases and are typically linked to worsening HF. Hospitalizations for HF occur in people with known HF who are probably already taking BBs. An increasing body of evidence in this cohort points to a prognosis benefit when BB treatment is sustained.