Dying and death in modern era, essential to look back running title - dying and death in modern era

Received: 10-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. PULHPM-22-5258; Editor assigned: 12-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. PULHPM-22-5258 (PQ); Accepted Date: Aug 30, 2022; Reviewed: 24-Aug-2022 QC No. PULHPM-22-5258 (Q) ; Revised: 26-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. PULHPM-22-5258 (R); Published: 03-Sep-2022, DOI: 10.37532/pulhpm.22.5 (5).50-52

Citation: Chhabra S, Dying and death in modern era, essential to look back running title - dying and death in modern era. J Health Pol Manage. 2022; 5(5):50-52.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

INTRODUCTION: There are complex interactions between biological, psychological, socioeconomic factors which affect care of people nearing end of life. How and where people die has changed radically in recent times. For some attempts are made to delay death by trying to prolong life with support system.

OBJECTIVES: To get information in relation to happenings around dying, death and their determinants.

MATERIAL METHODS: Information in relation to objectives, studies, and reviews and opinions was collected using available search engines.

RESULTS: In absence of immortality, society developed rites, rituals to help in passing of life, to honor dying / dead. Dying used to be religious spiritual process, not just physiological event. Now there is excessive focus on clinical interventions during the end of life, losing sight of many traditions. Many interrelated social, cultural, economic, religious, political factors determine happenings during dying, death. Believed to be potentially appropriate, treatment is continued with hopes of cure or better life or just to prolong life for other reasons, even exploitation in present era of consumerism! While many dying are over treated in health facilities, family’s friends may or may not be around. But many dying remain undertreated, or untreated and die without access to care, even pain relief. Reasons are complex, not just resources! Without birth there would be no death. Death is certain, essential for new life. For holistic care of dying, health systems are beginning to work in partnership with families of dying, public with relook at relationships, networks, which have been replaced by professionals, their protocols. Dying, death allows new ideas, new ways in spite of all odds. Death also reminds fragility of life, about sameness, as everyone has to die and all die. Health professionals are realizing inadequacy of their knowledge of an issue which fundamentally, unavoidably affects them too.

Keywords

Dying; Death; End of life care; Determinants; Health facilities

Introduction

How and where people die has changed radically in recent times. Attempts are made to delay death and prolong life with support system for many, including those with chronic illnesses, cancers and other such illnesses. Also people having many disorders at one time, including disorders related to ageing are now living longer. So there is a significant aging population. Consequently, there is increase in the numbers of people who present to emergency departments seeking care at the end of life. With the increase in demand for end-of-life care in emergency departments, a gap has also become visible about what is done and what is really needed. There are complex interactions between biological, psychological, and socioeconomic factors which affect care of people nearing the end of life. Many interrelated social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors determine the happenings during dying and death. Believed to be potentially appropriate, treatment is often continued at the end of life with the hopes of cure or better life or just to prolong life or may be for other reasons in the present era of consumerism! While many deaths are over-treated in hospitals with glittering technology with families and friends may or may not be around. Many dying remain undertreated, or untreated and die even with preventable conditions, without access to care, even without getting pain relief. Family also may not want to take them to health facilities, may be because of lack of resources or attitude of family. Also some are left to the health facilities because families almost disown knowing the needs of dying in the present materialistic era! Dying used to be a traditional and spiritual process, not just a physiological event. Over all for many dying and death have moved from traditional family and community settings to primarily the domain of health systems. The roles of families and communities have receded and dying and death have become unfamiliar for them. It is essential that dying and death are understood, and are managed with compassion and humanism. The unbalanced and contradictory picture of dying and death needs discussions and brain storming for reforms needed.

Objectives

To get information in relation to happenings around dying and death and their determinants.

Material and Methods

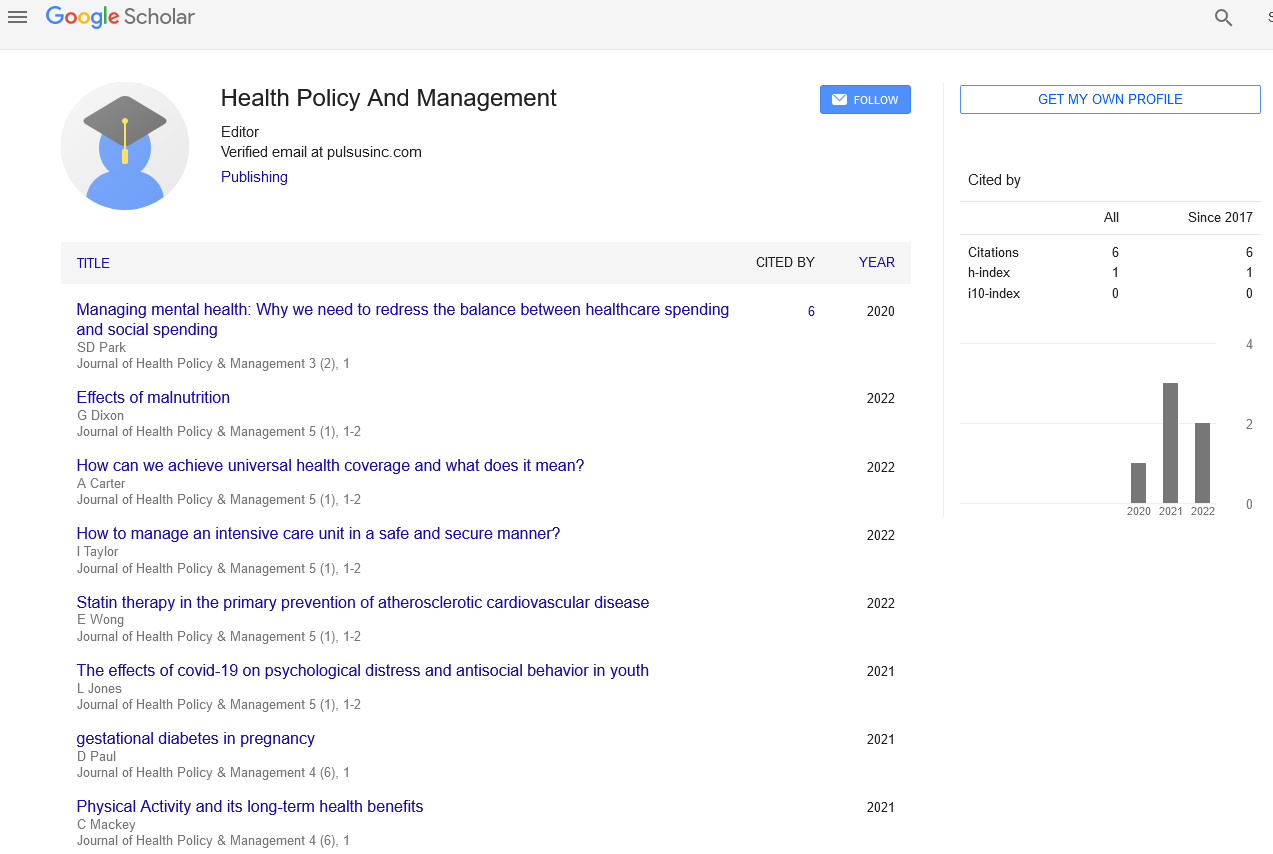

Information in relation to the objectives studies, reviews and opinions in English language, irrespective of the type was collected by using available search engines like Google, Google Scholar, Sci.Hub, yahoo etc.

Results and Discussions

The holistic approach in health care has been recognized by many researchers as essential for healing and health. Similarly dying and death have to be addressed. In modern days issues around dying and death are many, before as well as after death. O’gorman et al. opined that in the first half of the 20th century, society lost sight of the importance of rituals associated with dying and death and of the need for appropriate education [1]. Consequently patients and professionals found themselves unable to cope with the inevitability of death. Fear supplanted hope, and the health and well-being of society was deleteriously influenced. Gordon reported that in the absence of immortality, over the millennia society developed rites and rituals to help in the passing of life, to honor the person who was dying or died [2]. Dying used to be religious and spiritual process rather than simply physiological event but not so in the modern era. Erdmann et al did a review about talking about the end of life, communication patterns in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [3]. Researchers opined that ALS lead to death on an average in 2 years-4 years after the onset of symptoms. Although many people with the disease decided in favor of life-sustaining measures, but some considered hastening death too. Researchers also opined that avoiding or delaying communication, decision making and planning, as well as ignoring or disregarding the patients’ wishes by health care providers be judged as a violation of the ethical principles of autonomy and non-malfeasance. Omoya did a study in Australia to understand the lived experiences of emergency department doctors and nurses concerning, dying, death and end-of-life care provision [4]. Results indicated that challenges existed in the decision-making process of end-of-life care in emergency departments. Sallnow et al. opined that caring for the dying was a gift and much of the value of death was no longer recognized in the modern world, discovering this value can help care at the end of life and enhance living too [5]. Because conversations about dying and death can be difficult doctors, patients, or families may find it easier to avoid talk of death altogether and continue treatment knowing the results. Sinclair did a study about impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals and reported that much less is known about how such experiences incorporated into their personal lives and clinical practices [6]. Participants reported that their work provided a unique opportunity for them to discover meaning in life through lessons of their patients, and an opportunity to incorporate the teachings in their own lives. Although Western society’s culture has been described as a “death-denying” culture, the participants felt that their frequent exposure to dying and death was largely positive with curiosity about the continuity of life. During the second half of the century, there has been a proliferation of thanatology research. Health professionals are realizing the inadequacy of their knowledge of an issue which fundamentally and unavoidably affected everyone, including themselves. Widyaningsih reported that the concept of palliative care was closely related to perceived good death [7]. The person’s preferences for the dying process. These preferences might include how, where, when, pain-free status of dying process should take place as being said good death or successful dying [8, 9]. The concept of good death also included who accompanied the person during the dying process and the manner of facing death awareness and readiness of the dying process, natural or sudden death [8, 10]. However a lot of research is needed about griefing in death after prolonged attempts of saving life and sudden death and also when elderly die or young or children die. Ironically, studies have shown that when patients with contagious diseases were isolated from their family members due to hospital policies and many of them had a deep fear of dying alone, without dear ones round [9, 11]. Majority of people wanted to be with their loved ones around when their lives came to an end [9, 12]. Palliative care can provide better outcomes for patients and cares, leading to improved quality of life and often at a lower cost. But attempts to influence on healthcare services have had limited success. Palliative care broadly remains a service-based response to the social concern. Study by Sanders revealed that significantly higher intensities of grief were noted in parents surviving their child’s death [13]. A distinct number of physiological symptoms were noted in the bereaved group compared to the controls. Frequent church attenders were more likely to respond with higher optimism and social desirability but more repression of bereavement responses than were in less frequent church attendees. Income did not appear to contribute negatively to bereavement itself but rather to the constellation of debilitating variables which surrounded thosewith lowincome. Therewere no differences inbereavement intensities between those who had death after chronic-illnesses compared with sudden death situations. Although reducing the prevalence of health risk behaviors in low-income populations is an important public health goal, differences in deaths are due to a wider array of factors and, therefore, would persist even with improved health behaviors among the disadvantaged. Kothari et al. opined that natural death did not come to pass because of some (replaceable) missing element, but because of the evolution of the individual from womb to tomb was at its final destination [14]. To accept death as a physiologic event is to advance technology and to disburden health facilities of a lot of avoidable thinking and doing. Fitzsimmons et al. reported in ‘One Man’s Death His Family’s Ethnography’ that every family member who completed the grieving process used a different metaphor when describing death [15]. These metaphors impaled growth or change. The data suggested that euphemism for death were utilized when the grieving process was not completed. Study by Jacques intended to help occupational therapists better understand the meaning of occupation surrounding dying and death at a small residential hospice in the Midwestern United States. Residents, their families, and hospice staff participated in a six months ethnographic study involving participant’s observations, interviews with staff. Four domains of occupation were identified as elements of the dying experience continuing life, preparation for death, waiting death and after-death [16]. In the context of dying, both mundane and unique occupations took on new form of significance to the residents, families, and caregivers. These findings contributed to the understanding of the nature and meaning of occupation and how occupation created the good death. Croker et al. did a study for developing a meta-understanding of human aspects of providing palliative care and reported that there was need of recognizing the individuality of people, their varied involvements, situations, understanding and responses, and the difficulty in stepping back to get a whole view of the whole being in the midst of providing palliative care [17].

Researchers reported that their meta-understanding of human aspects of providing palliative care and reported that there was need of recognizing the individuality of people, their varied involvements, situations, understanding and responses, and the difficulty in stepping back to get a whole view of the whole being in the midst of providing palliative care [17]. Researchers reported that their meta-understanding of human aspects of providing palliative care, represented diagrammatically in a model, was composed of attributes of humanity and actions of caring. Attributes of humanity were death’s inevitability, sufferings’ variability, compassion’s dynamic nature, and hope’s precariousness. Actions of caring included recognizing and responding, aligning expectations, valuing relationships, and using resources wisely. The meta-understanding was a framework to keep multiple complex concepts in view as they interrelated with each other. Blüher et al. opined that there has been an excessive focus on clinical interventions at the end of life, losing sight of many things [18]. Philosophers and theologians from around the world have recognized the value that death holds for human life. Birth and death are bound together. Without birth there would be no death and death is certain and essential for balance for welcoming new life. Communities around the world from varied geographies are challenging norms and rules about caring for dying and models of civil societies and, compassionate community actions are emerging. The challenge of transforming how people die has been recognized and responded by many around the world. Systems are constantly changing, and many programs are underway that encourage the rebalancing of relationships with dying and death. As consequence, what constitutes a desired or appropriate place is routinely defined in a very simple and static ‘geographical’ way, that is linked to conceptualizing death as an unambiguous and discrete event that happens at a precise moment at a specific location instead of place of death merely defined in geographic terms. The palliative care staff look at the much more dynamic relation between patients and their location as they approached the end of life and interacted with, living persons ‘placing work’ to capture efforts. Policy and legislation changes are recognizing the impact of bereavement and supporting the availability of medication to manage pain nearing the end of life. Hospitals are changing their culture to openly acknowledge dying and death. Sallnow et al opined that health systems were beginning to work in partnership with patients, families, and the public on these issues to integrate holistic care of the dying to have a relook at relationships and networks which have been replaced by the professionals and their protocols [5]. Researchers also opined that communities are reclaiming dying and death as social concerns. Restrictive policies on pain relief availability are being transformed and health-care professionals are working in partnership with civil societies and families. But a lot more is needed. Driessen et al. reported that over the last decade countries have promoted policies, opportunity to decide for patients at the end of life to be able to choose where to die [19]. Central to this is the expectations that in most instances people would prefer to die at home, where they are more likely to feel most comfortable and less medicalized. In doing so recording the preferred place of death, reducing the number of hospital deaths have become common measure of the overall quality care of life. To achieve the ambition to rebalance dying and death, radical changes across health systems are needed. It is the responsibility of global bodies, governments, and health systems to take up this challenge. In Kerala, India, over the past three decades the process of dying and death have been reclaimed as a social concern and responsibility through a broad social movement comprised of tens of thousands of volunteers complemented by changes in political, legal, and health systems [20]. Lancet Commission the value of death provided recommendations to policy makers, governments, civil society, and health and social care systems [5]. To achieve the ambition of radical change across the systems, death and dying must be recognized as not only normality, but valuable for rebalanced care of the dying and grieving. People needed to respond to the challenges. Some people are over treated in hospitals with families relegated to the margins as treatment nearing the end of life may be costly and a cause of families falling into poverty in countries without universal health coverage. Cost is always there, as with UHC cost is on the health system. Sallnow et al. reported that in high-income countries between 8% to 11/% of annual health expenditure for the entire population was spent on the less than 1% who die in a year [21]. Some of this high expenditure may be really essential, but there is evidence that patients and health professionals hope for better outcomes than real and treatment that is either intended to cure or to help a person survive with better life is often continued for too long at the end of life. Also the disadvantaged and powerless suffer most from the imbalance in care for those who are dying and grieving in low resource and high income communities. Some are victims of consumerism and remain in health facilities or left to die, others never reach health facility and die even without pain relief in the materialistic world. Many inter-related social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors determine how dying and death, bereavement is understood, experienced, and managed. Dying and death allow new ideas and new ways. The Lancet Commission on the value of death set out five principles for a new vision of how death and dying could be. The five principles are the social determinants of death, dying, and grieving are tackled; dying is understood to be relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event, network of care lead support for dying, caring and grieving; conversations and stories about everyday dying, death, and grief become common; and death is recognized as having value [22].

Conclusion

Systems are constantly changing, and many programs are underway that encourage the rebalancing of relationship of dying, death, and grieving. But these innovations do not amount to the real system change. Rebalancing dying and death will depend on changes across death systems. Death also reminds the fragility of life and also in spite of all odds, about sameness, as everyone has to die and all die. Philosophers and many careers, both lay and professionals have recognized this fact.

References

- Oâ??gorman SM. Death and dying in contemporary society: an evaluation of current attitudes and the rituals associated with death and dying and their relevance to recent understandings of health and healing. J Advan Nur 1998; 27(6):1127-1135. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Gordon M. Rituals in death and dying: Modern medical technologies enter the Fray. Rambam Maimonides Med J 2015; 6(1). [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Erdmann A, Spoden C, Hirschberg I, et al. Talking about the end of life: Communication patterns in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-a scoping review. Palliat Care Social Prac 2022; 16:26323524221083676. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Omoya OT, De Bellis A, Breaden K. Death, dying, and end-of-life care provision by doctors and nurses in the emergency department: A phenomenological study. J Hospice Palliat Nur 2022; 24(2):E48-57. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Report of the lancet commission on the value of death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022; 399(10327):837-884. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sinclair S. Impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals. CMAJ 2011; 183(2):180-187. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Widyaningsih V, Febrinasari RP, Suwandono A, et al. Palliative care and good death in acute diseases: A scoping review protocol. F1000 Res 2021; 10(1147):1147. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Montross-Thomas LP, et al. Defining a good death (successful dying): Literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24(4): 261-271. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Campbell SM. Well-being and the good death. Ethical Theory Moral Pract Aug 2020; 23(3-4): 607-623. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, et al. Good death inventory: A measure for evaluating good death from the bereaved family memberâ??s perspective. J Pain Sympt Manage 2008; 35(5): 486-498. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Proulx K, Jacelon C. Dying with dignity: The good patient versus the good death. Am J Hospice Palliative Med 2004; 21(2):116-120. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Borgstrom E. What is a good death? A critical discourse policy analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat Care 2020. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sanders CM. A comparison of adult bereavement in the death of a spouse, child, and parent. J Death Dying 1980; 10(4):303-322. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Kothari ML, Mehta LA, Kothari VM. Cause of death--so-called designed event acclimaxing timed happenings. J Postgraduate Med 2000; 46(1):43-51. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Fitzsimmons E. One man's death: His family's ethnography. OMEGA-J Death Dying 1995; 30(1): 23-39. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Jacques ND, Hasselkus BR. The nature of occupation surrounding dying and death. Occup Particip Health 2004; 24(2):44-53. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Croker A, Fisher K, Hungerford P, et al. Developing a meta-understanding of â??human aspectsâ?? of providing palliative care. Palliative Care Social Prac 2022; 16:26323524221083679. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Blüher M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature Rev Endocrinol 2019; 15(5):288-298. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Driessen A, Borgstrom E, Cohn S. Placing death and dying: making place at the end of life. Social Sci Med 2021; 291:113974. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- THE LANCET: Experts warn of the increasing overmedicalization of death, call for radical rethink of how society cares for dying people. 2022.

- Sallnow L, Chenganakkattil S. The role of religious, social and political groups in palliative care in Northern Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care 2005; 11: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Report of the lancet commission on the value of death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022; 399(10327): 837-884. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]