Elongated styloid process – report of two rare cases

Sanjeev Iranna Kolagi1*, Anita Herur2 and Ashwini Mutalik1

1Department of Anatomy, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India

2Department of Physiology, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Sanjeev Iranna Kolagi

Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot Karnataka, 587102, India

Tel: +91 973 1798355

E-mail: drsanjeevkolagi@yahoo.co.in

Date of Received: April 27th, 2010

Date of Accepted: June 29th, 2010

Published Online: August 2nd, 2010

© Int J Anat Var (IJAV). 2010; 3: 100–102.

[ft_below_content] =>Keywords

styloid process, temporal bone, elongation, Eagle’s syndrome, dry skull

Introduction

Styloid process of temporal bone is a slender projection attached to base of the skull and extends downwards, forwards and slightly medially. From its extremity the stylohyoid ligament passes downwards and forwards to the lesser horns of hyoid bone. The process is covered laterally by the parotid gland, facial nerve crosses its base and the external carotid artery crosses its tip, as they lie within the gland. The anterior surface of styloid gives origin to styloglossus muscle, its tip to stylohyoid muscle. On its deep surface the process is separated from internal jugular vein by the origin of stylopharyngeus muscle [1].

The length of the styloid process is usually 2–3 cm [2]. When it is more than 3 cm it is called as elongated styloid process, and it can cause pain in throat, difficulty in swallowing, foreign body sensation, carotid artery compression syndrome, etc. This elongation was first described in 1652 by Italian surgeon Pietro Marchetti. In 1937, Watt W. Eagle coined the term stylalgia to describe the pain associated with elongation of styloid process [3].

The styloid process is normally composed of dense connective tissue in adults but may retain its embryonic cartilage and the potential for ossification [4].

On review of literature, there were many case reports of elongated styloid but there were no reports of such a long and thick styloid process.

Case Report

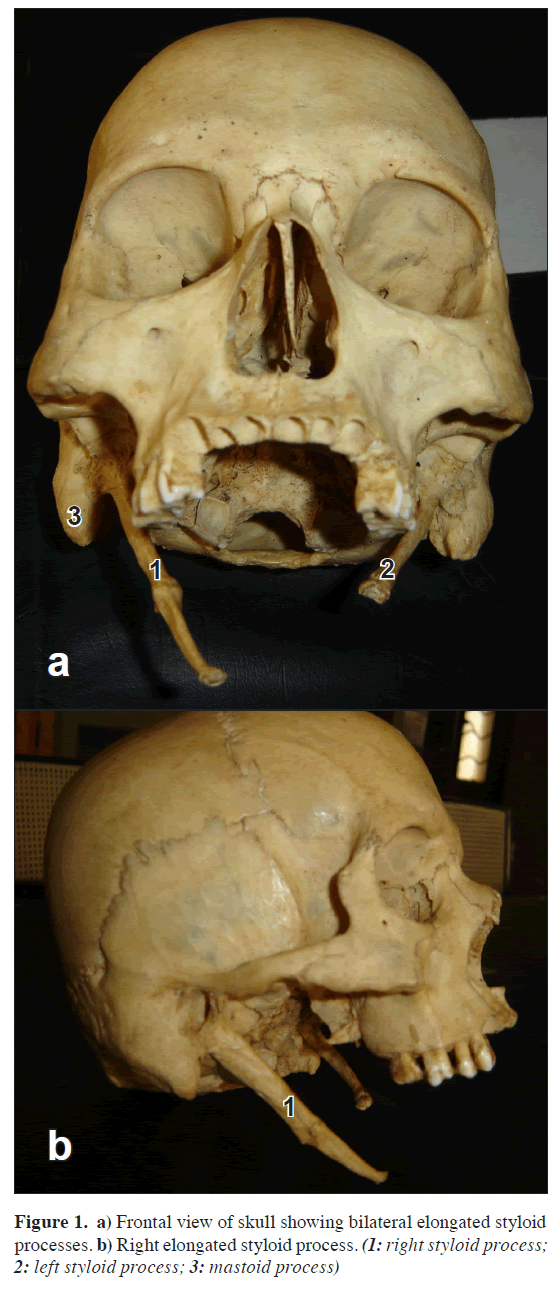

During the routine osteological study of skull, we came across a skull which was extreme example of bilateral elongated styloid process with ossified stylohyoid ligament. The total length of the process was 8 cm and it was 1 cm thick at the base, which is extremely rare (Figure 1, stylohyoid part broken on left side). Styloid process proper was 5 cm long and remaining 3 cm was ossified stylohyoid ligament, the junction between the two was marked by bulge of bony mass.

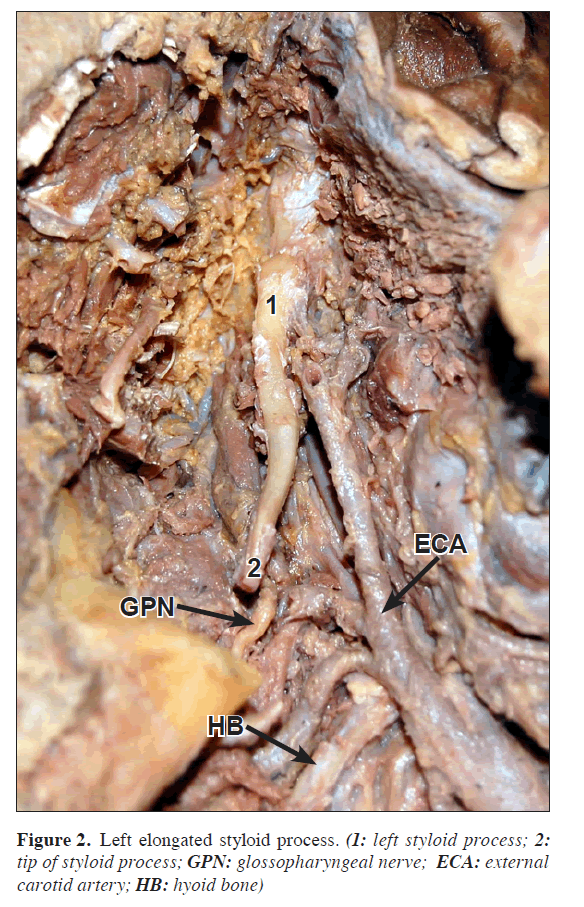

In the other case, on left side of a male cadaver, the styloid process was 6.3 cm long and 1 cm thick at the base. The right side styloid was of normal length (Figure 2).

Discussion

The stylohyoid chain components are derived embryologically from the first and second branchial arches in four distinct segments: tympanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal segments. These segments are derived from Reichert’s cartilages that ossify in two parts. The styloid process develops from the tympanohyal and stylohyal segments that usually fuse at puberty. The lesser horn of the hyoid bone arises from the hypohyal segment. Connecting these two structures, the stylohyoid ligament originates from the ceratohyal segment [4].

The styloid process and the stylohyoid ligament have been linked to Eagle’s syndrome, which has a symptomatology characterized by the sensation of having a foreign body in the pharynx, causing difficult and painful swallowing and earache. It has also been referred to as styloid syndrome, stylohyoid syndrome, stylalgia, stylohyoid disorder, neuralgia of styloid process, cervicopharyngeal pain syndrome. It can also cause vertigo, tinnitus, dysphonia, carotidynia, pain on turning the head, reduced mandibular opening, and change in voice, hypersalivation, and even alteration in taste [4]. Although 4% of the population is thought to have an elongated styloid, only 4–10% of this group is symptomatic [5]. Frommer observed that the direction and curvature of styloid process were more important than its length in causing symptoms [6].

In the study of Massey, there were only 11 cases of styloid process having length of more than 4 cm out of 2000 cases studied[7]. Harma gives incidence of 4-7%for elongated styloid process[8]. Elongation was seen four times more in males than females and in 75% of cases the elongation was bilateral [9].

There are many reports of elongated styloid process but all of them have measured only the length. There were no reports of such thick and long process like our case in literature.

The pathophysiological mechanism of symptoms is not very clear. The following theories are proposed [10]:

• Traumatic fracture of styloid causing proliferation of granulation tissue, which compresses the adjacent structures.

• Compression of adjacent nerves, glossopharyngeal, lower branch of trigeminal or chorda tympani.

• Stylohyoid insertion tendonitis.

• Irritation of pharyngeal mucosa by direct compression or post tonsillectomy scarring.

• Impingement of carotid vessels, producing irritation of sympathetic nerves in the arterial sheath.

Actual cause of elongation is poorly understood. Several theories are proposed [10]:

• congenital elongation due to persistence of a cartilaginous analog of stylohyal.

• calcification of the stylohyoid ligament by an unknown process.

• growth of osseous tissue at the insertion of the stylohyoid ligament.

References

- Williams PL. Gray’s Anatomy. 38th Ed., London, ELBS with Churchill Livingstone. 1999; 592.

- Sokler K, Sandev S. New classification of the styloid process length--clinical application on the biological base. Coll Anthropol. 2001; 25: 627–632.

- Kim E, Hansen K, Frizzi J. Eagle syndrome: case report and review of literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008; 87: 631–633.

- Rodriguez-Vazquez JF, Merida-Velasco JR, Verdugo-Lopez S, Sanchez-Montesinos I, Merida-Velasco JA. Morphogenesis of the second pharyngeal arch cartilage (Reichert’s cartilage) in human embryos. J Anat. 2006; 208: 179–189.

- Restrepo S, Palacios E, Rojas R. Eagle’s syndrome - Imaging Clinic. Ear Nose Throat J. Oct 2002. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BUM/is_10_81/ai_93916091 (accessed December 10th 2009).

- Frommer J. Anatomic variations in the stylohyoid chain and their possible clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974: 38: 659–667.

- Massey EW. Facial pain from an elongated styloid process. (Eagles syndrome). South Med J .1978; 71: 1156–1159.

- Harma R. Stylalgia: clinical experiences of 52 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 1966; suppl 224: 149+.

- Cawich SO, Gardner M, Shetty R, Harding HE. A post mortem study of elongated styloid processes in a Jamaican population. The Internet Journal of Biological Anthropology. 2009; Volume 3: Number 1.

- Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with eagle syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001; 22: 1401–1402.

Sanjeev Iranna Kolagi1*, Anita Herur2 and Ashwini Mutalik1

1Department of Anatomy, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India

2Department of Physiology, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot, Karnataka, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Sanjeev Iranna Kolagi

Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, S. N. Medical College, Navanagar, Bagalkot Karnataka, 587102, India

Tel: +91 973 1798355

E-mail: drsanjeevkolagi@yahoo.co.in

Date of Received: April 27th, 2010

Date of Accepted: June 29th, 2010

Published Online: August 2nd, 2010

© Int J Anat Var (IJAV). 2010; 3: 100–102.

Abstract

We came across an adult human dry skull, which had bilateral elongated styloid process. Total length of the process was 8 cm and it was 1 cm thick at the base. Styloid process proper was 5 cm long and remaining 3 cm was ossified stylohyoid ligament. In another case, on left side of a male cadaver the styloid process was 6.3 cm long and 1 cm thick at the base. The right side styloid was of normal length.

-Keywords

styloid process, temporal bone, elongation, Eagle’s syndrome, dry skull

Introduction

Styloid process of temporal bone is a slender projection attached to base of the skull and extends downwards, forwards and slightly medially. From its extremity the stylohyoid ligament passes downwards and forwards to the lesser horns of hyoid bone. The process is covered laterally by the parotid gland, facial nerve crosses its base and the external carotid artery crosses its tip, as they lie within the gland. The anterior surface of styloid gives origin to styloglossus muscle, its tip to stylohyoid muscle. On its deep surface the process is separated from internal jugular vein by the origin of stylopharyngeus muscle [1].

The length of the styloid process is usually 2–3 cm [2]. When it is more than 3 cm it is called as elongated styloid process, and it can cause pain in throat, difficulty in swallowing, foreign body sensation, carotid artery compression syndrome, etc. This elongation was first described in 1652 by Italian surgeon Pietro Marchetti. In 1937, Watt W. Eagle coined the term stylalgia to describe the pain associated with elongation of styloid process [3].

The styloid process is normally composed of dense connective tissue in adults but may retain its embryonic cartilage and the potential for ossification [4].

On review of literature, there were many case reports of elongated styloid but there were no reports of such a long and thick styloid process.

Case Report

During the routine osteological study of skull, we came across a skull which was extreme example of bilateral elongated styloid process with ossified stylohyoid ligament. The total length of the process was 8 cm and it was 1 cm thick at the base, which is extremely rare (Figure 1, stylohyoid part broken on left side). Styloid process proper was 5 cm long and remaining 3 cm was ossified stylohyoid ligament, the junction between the two was marked by bulge of bony mass.

In the other case, on left side of a male cadaver, the styloid process was 6.3 cm long and 1 cm thick at the base. The right side styloid was of normal length (Figure 2).

Discussion

The stylohyoid chain components are derived embryologically from the first and second branchial arches in four distinct segments: tympanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal segments. These segments are derived from Reichert’s cartilages that ossify in two parts. The styloid process develops from the tympanohyal and stylohyal segments that usually fuse at puberty. The lesser horn of the hyoid bone arises from the hypohyal segment. Connecting these two structures, the stylohyoid ligament originates from the ceratohyal segment [4].

The styloid process and the stylohyoid ligament have been linked to Eagle’s syndrome, which has a symptomatology characterized by the sensation of having a foreign body in the pharynx, causing difficult and painful swallowing and earache. It has also been referred to as styloid syndrome, stylohyoid syndrome, stylalgia, stylohyoid disorder, neuralgia of styloid process, cervicopharyngeal pain syndrome. It can also cause vertigo, tinnitus, dysphonia, carotidynia, pain on turning the head, reduced mandibular opening, and change in voice, hypersalivation, and even alteration in taste [4]. Although 4% of the population is thought to have an elongated styloid, only 4–10% of this group is symptomatic [5]. Frommer observed that the direction and curvature of styloid process were more important than its length in causing symptoms [6].

In the study of Massey, there were only 11 cases of styloid process having length of more than 4 cm out of 2000 cases studied[7]. Harma gives incidence of 4-7%for elongated styloid process[8]. Elongation was seen four times more in males than females and in 75% of cases the elongation was bilateral [9].

There are many reports of elongated styloid process but all of them have measured only the length. There were no reports of such thick and long process like our case in literature.

The pathophysiological mechanism of symptoms is not very clear. The following theories are proposed [10]:

• Traumatic fracture of styloid causing proliferation of granulation tissue, which compresses the adjacent structures.

• Compression of adjacent nerves, glossopharyngeal, lower branch of trigeminal or chorda tympani.

• Stylohyoid insertion tendonitis.

• Irritation of pharyngeal mucosa by direct compression or post tonsillectomy scarring.

• Impingement of carotid vessels, producing irritation of sympathetic nerves in the arterial sheath.

Actual cause of elongation is poorly understood. Several theories are proposed [10]:

• congenital elongation due to persistence of a cartilaginous analog of stylohyal.

• calcification of the stylohyoid ligament by an unknown process.

• growth of osseous tissue at the insertion of the stylohyoid ligament.

References

- Williams PL. Gray’s Anatomy. 38th Ed., London, ELBS with Churchill Livingstone. 1999; 592.

- Sokler K, Sandev S. New classification of the styloid process length--clinical application on the biological base. Coll Anthropol. 2001; 25: 627–632.

- Kim E, Hansen K, Frizzi J. Eagle syndrome: case report and review of literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008; 87: 631–633.

- Rodriguez-Vazquez JF, Merida-Velasco JR, Verdugo-Lopez S, Sanchez-Montesinos I, Merida-Velasco JA. Morphogenesis of the second pharyngeal arch cartilage (Reichert’s cartilage) in human embryos. J Anat. 2006; 208: 179–189.

- Restrepo S, Palacios E, Rojas R. Eagle’s syndrome - Imaging Clinic. Ear Nose Throat J. Oct 2002. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BUM/is_10_81/ai_93916091 (accessed December 10th 2009).

- Frommer J. Anatomic variations in the stylohyoid chain and their possible clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974: 38: 659–667.

- Massey EW. Facial pain from an elongated styloid process. (Eagles syndrome). South Med J .1978; 71: 1156–1159.

- Harma R. Stylalgia: clinical experiences of 52 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 1966; suppl 224: 149+.

- Cawich SO, Gardner M, Shetty R, Harding HE. A post mortem study of elongated styloid processes in a Jamaican population. The Internet Journal of Biological Anthropology. 2009; Volume 3: Number 1.

- Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with eagle syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001; 22: 1401–1402.