Feeding issues in young children with autism spectrum disorder in a multi-ethnic population include avoidant restrictive food intake disorder.

#Equally contribution

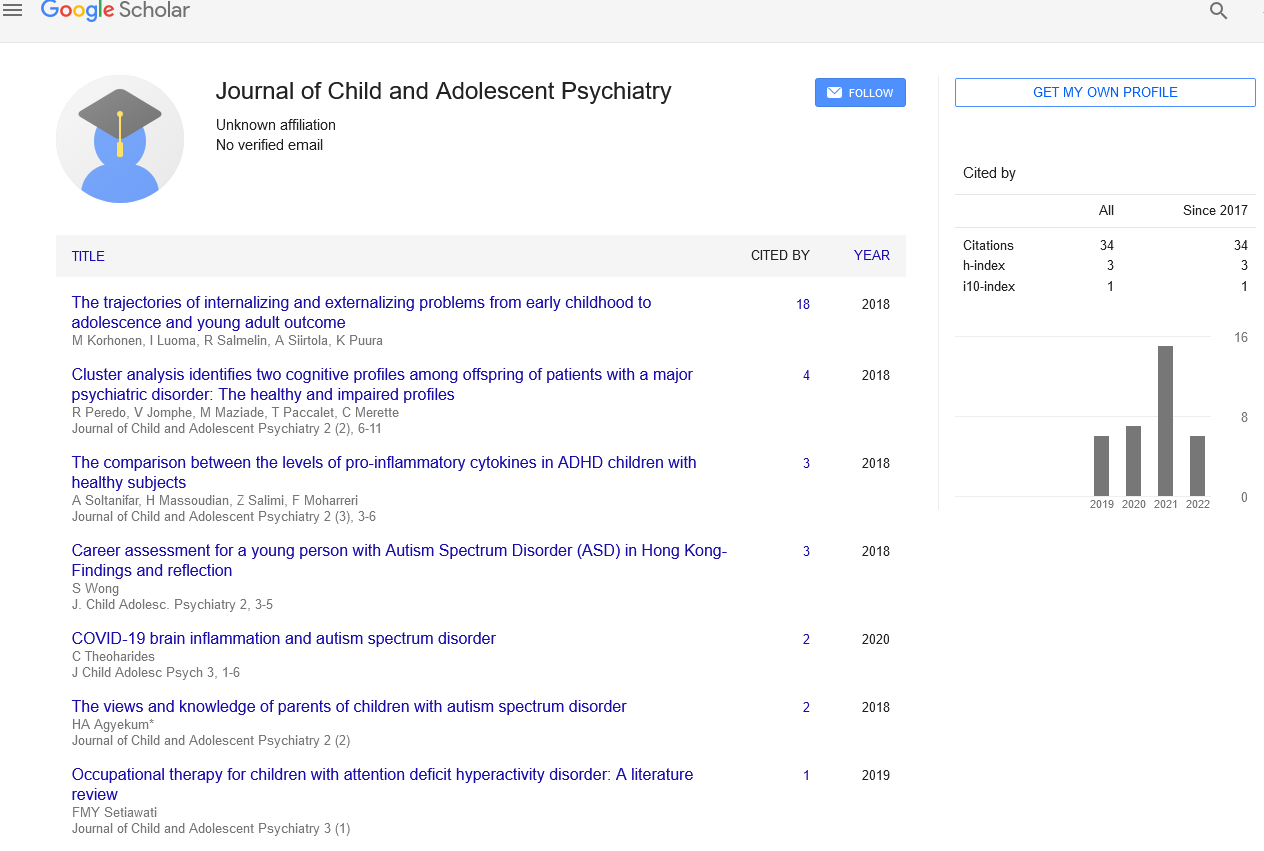

Received: 04-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5436; Editor assigned: 12-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. PULJCAP-22-5436(PQ); Accepted Date: Aug 30, 2022; Reviewed: 16-Aug-2022 QC No. PULJCAP-22-5436(Q); Revised: 27-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5436(R); Published: 04-Sep-2022, DOI: 10.37532/puljcap.2022.6(5);30-31.

Citation: James S. Feeding issues in young children with autism spectrum disorder in a multi-ethnic population include avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. J Child Adolescence Psychiatry. 2022; 6(5):30-31

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

We looked at feeding issues in preschool-aged children with autism spectrum disorders, including Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) (ASD). A prospective longitudinal study included 46 children with ASD. 76% of the children with ASD had feeding issues, and 28% of them satisfied the requirements for ARFID. The study emphasises the early onset age, the diversity of eating difficulties, the necessity for multidisciplinary examinations in both feeding problems and ASD, as well as the need for greater clarification of the classifications of feeding disorders in children.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 50% to 90% of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) experience eating and feeding difficulties. Although research on early food abnormalities in ASD has been sparse, studies have shown that feeding issues may manifest very early in the course of ASD.

Early onset of ASD is significantly linked to abnormal responses to sensory inputs as well as deficits in social communication and diminished joint attention practises. Problems with sensory perception, motor control, and emotional control may show prodromal symptoms as early as the first year of life. Regulatory difficulties (RPs) are frequently referred to as eating, sleeping, and excessive crying problems in infancy and are the most common reasons for parental worries and interaction with health services in the general child population. The risk of later developmental issues has been linked to persistent RPs. Early sleeping issues, irritability, negative affect, and distress reactions have all been found to be more common in new-borns with later-diagnosed ASD. According to a Swedish study, early RPs were more common in children who eventually obtained an ASD diagnosis than in the general population. Since the 1980s, but especially in the past ten years, significant incidences of comorbid neurodevelopmental and medical illnesses, including feeding abnormalities, have been linked to ASD. In order to highlight the overlap of symptoms and concomitant neurodevelopmental abnormalities in early childhood, Gillberg introduced the idea of Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations (ESSENCE) in 2010. One of the earliest and most difficult conditions to treat stands out as feeding issues.

As with all children, children with ASD may experience eating and feeding issues that are brought on by or linked to a variety of medical conditions, including food allergies, digestive issues, problems with oral and nasopharyngeal function, congenital heart disease, or neurological issues. According to studies, children with ASD have a higher prevalence of gastrointestinal issues, food allergies, and medical co-morbidities in general than children who are typically developing. ADHD and other concomitant neurodevelopmental disorders may also have an impact on feeding. It is logical to think that many times a number of things combine to cause eating issues. In every situation, it is necessary to investigate the family's psychosocial issues, lack of support, and everyday routines. Additionally, research has indicated that parental feeding habits might influence frequent feeding issues in children and that children from economically disadvantaged groups are more likely to be thin. Eating and eating difficulties can range from minor, temporary issues to serious behavioural and/or medical feeding abnormalities. To address the diversity of the etiologies and clinical manifestations of eating disorders, there are presently no standardised names and definitions for feeding difficulties or completely distinct diagnostic classifications. The diagnostic codes for paediatric feeding disorders in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), either require the absence of an organic disease to code "Feeding disorders of infancy and childhood" or use the general "Feeding difficulties and mismanagement." To our knowledge, these two ICD-10 diagnosis codes have been used the most frequently in clinical settings for eating issues in kids with ASD. The ICD-11 categories and criteria will not be further explored here because they were not available at the time of conducting the present study. A larger notion of paediatric eating disorders has recently been presented in order to thoroughly include all elements of feeding disorders. The International Statistical Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework has been used by an interdisciplinary consensus group to define PFD as "impaired oral intake that is not age-appropriate and associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction." The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, added the diagnosis of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) in 2013 (DSM-5). The diagnosis has no age restrictions and manifests as an inability to meet dietary and/or energy requirements, which results in 31 at least one of the following: weight loss or failure to gain weight appropriately; a nutritional deficiency; a reliance on enteral feeding or nutritional supplements; or a significant disruption of psychosocial functioning. There is little information available about the clinical features of ARFID. ARFID has a complicated aetiology, and it has been suggested that it shares symptoms with other neurodevelopmental diseases, which is in line with the idea of ESSENCE. ARFID was reported to be more prevalent in younger children (4 years–9 years old) and in kids with concomitant ASD in a recent study by Farag et al. According to studies, ARFID can appear in three ways that frequently overlap: lack of interest in food; restricted eating brought on by sensory sensitivity; and avoidance of food out of concern for unfavourable outcomes. Sharp and Stubbs have suggested subtyping ARFID according to the age of onset and whether eating difficulties are caused by volume or diversity.