Health disparities among the South Asians in the United States

Received: 04-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-23-6848; Editor assigned: 07-Nov-2023, Pre QC No. PULJNRP-23-6848 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Nov-2023 QC No. PULJNRP-23-6848; Revised: 02-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-23-6848 (R); Published: 09-Jan-2024

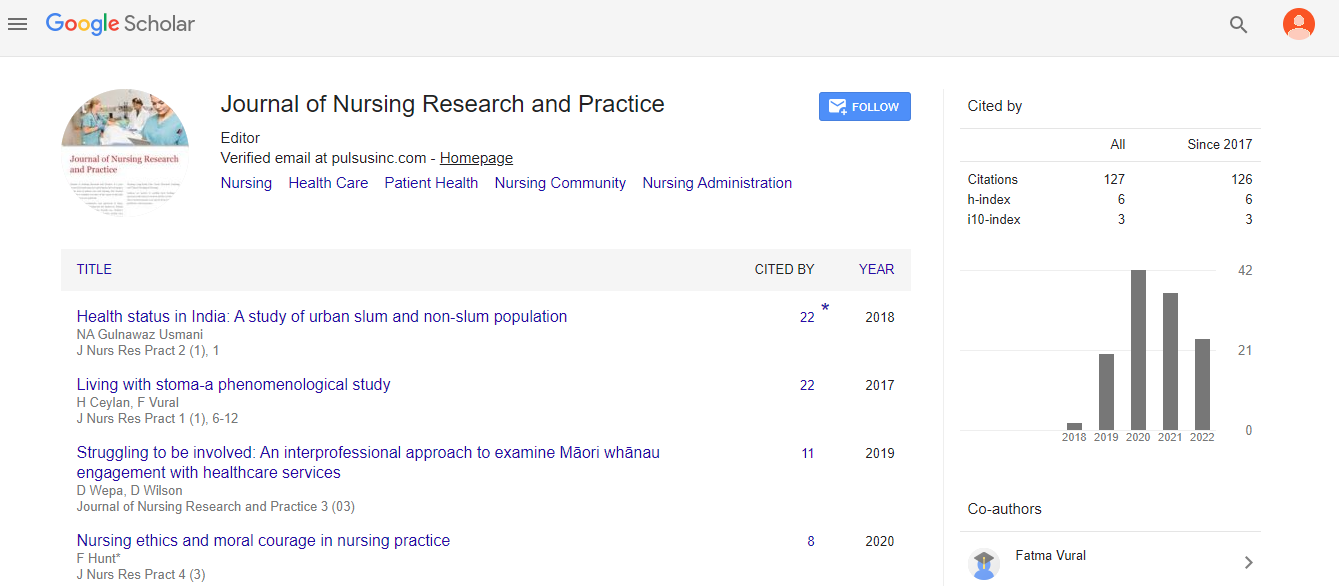

Citation: Mathews N, Joseph S. Health disparities among the South Asians in the United States. J Nurs Res Pract. 2024;8(1):1-3.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Purpose of review: The main purpose of this review is to summarize the health disparities among the South Asian population in the United States.

Findings: The review showed the various health disparities among the South Asian population in the United States. The observed health disparities among the South Asian population were mental health disorders, colorectal cancer, overweight/obesity, hypertension, racial violence and discrimination, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Summary: The health disparities among the South Asian population are significant and have to be addressed in a culturally tailored manner for better healthcare outcomes. There must be greater collaboration among healthcare workers, providers, and community leaders better to understand health disparities among the South Asian population. Future recommendations strongly suggest conducting more studies on the South Asian population to know the extent of these health disparities considering the social determinants of health factors.

Keywords

Health disparity; South Asians; Diabetes; Obesity; Hypertension; Ethnic minorities; Mental health disorders; Colorectal cancer; Violence; Cardiovascular disease; Discrimination

Introduction

South Asian (SA) communities in the United States trace their roots to multiple countries in the Indian subcontinent (e.g., Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka). Its global diaspora, including descendants of laborers, was brought elsewhere due to British colonialism (e.g., Caribbean, Fiji, Eastern and Southern Africa). According to the 2010 US census, there were 3.5 million South Asians in the United States, which increased by roughly 60% to 5.6 million in 2019. This comprises roughly 25% of the Asian American population, 22 million or roughly 6.8% of the US population. It is projected that by 2055, the Asian American community will be the largest immigrant group in the United States; within that, Asian Indians will be the second largest subgroup [1].

Literature Review

This review focuses on health disparities among the South Asian population with a geographical focus on the United States. A CINAHL and the author's affiliate institutes' library databases were searched using the following primary key terms. Health disparity OR South Asians OR diabetes OR obesity OR hypertension OR ethnic minorities OR mental health disorders OR colorectal cancer OR violence OR cardiovascular disease OR discrimination. Articles were excluded if they were not relevant to health disparities among the South Asian population.

Discussion

Mental health disorders

Literature shows that South Asian (SA) immigrants undergo high rates of mental health disorders, which often go unaddressed. South Asians are susceptible to psychological distress due to migration and subsequent pressures to acculturate, and other social determinants of health significantly impact functioning and quality of life [2]. Stress resulting from actions to incorporate host country traits within one’s culture, also known as acculturative stress, can negatively affect mental health. Acculturative stress can include intergenerational conflict, discrimination, and depression [3]. Qualitative interviews with SA migrant families in New York city revealed that acculturative stress could impact multiple generational groups, including foreign-born parents and 1.5 generational children [4,5]. Literature also shows that perceived discrimination was positively and significantly associated with perceived stress among first and secondgeneration SAs ranging from 18 to 83 years old [6]. Cultural conflict surrounding gender has been identified as a significant source of stress for SA women [7].

Colorectal cancer

Population and community-based studies that have disaggregated data for the Asian American (AA) population have found lower Colorectal Cancer (CRC) screening rates, as low as 25%, for the SA population compared with other racial and ethnic groups [8-10]. Findings show that SAs consistently have among the lowest rates of CRC screening within NYC, between 45 and 58%, compared with non-Hispanic white (70.4%), non-Hispanic black (68.2%), and Hispanic (71.7%) [11,12]. Barriers and facilitators related to CRC screening in the South Asian population include social, acculturation, and access to care factors like limited English proficiency, education, and length of residence in the US. These are stronger predictors of CRC screening for SAs than cultural and health beliefs [13,14].

Patel et al., explored several common and unique challenges SA men and women face to obtain colorectal cancer screening [15]. These challenges can be categorized into sociocultural factors and structural factors. Under sociocultural factors, the most frequently cited challenge to CRC screening was a lack of information, knowledge, and unfamiliarity with the screening test procedure. Structural factors included financial challenges and support for in-language or translated information and resources to facilitate CRC screening.

Overweight, obesity, and hypertension

Literature shows that South Asian adults have substantially lower cutoff points for overweight and obesity than white Europeans, which are associated with higher risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [16,17]. Therefore, exploring the association between Body Mass Index (BMI) and hypertension has important public health implications in South Asian countries, where the burden of hypertension is high, and obesity is increasing at the population level [18-20].

There were significant associations between overweight obesity and hypertension, irrespective of cutoffs for defining overweight obesity and hypertension. Our study showed that almost one in every five adults aged 35 years and above in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal had hypertension [21]. BMI is associated with hypertension, diabetes, and other NCDs in South Asian populations at a much lower threshold level than the level for other populations [22-24]. The possible reasons for such differences could be genetic and metabolic variations and clustering of environmental, dietary, and social factors associated with hypertension [18,24,25]. The age-specific prevalence of hypertension is very high among men and women in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. The associations of BMI with hypertension are positive and robust across various population subgroups defined by socioeconomic groups. Public health interventions targeting reducing BMI at the population level would significantly reduce the burden of hypertension in South Asia [21].

Racial violence and discrimination

Despite abundant evidence of the adverse effects of violence on mental and physical health, there is limited research examining the impact of this racialized state violence on the health of South Asians in the United States. There is an urgent need for dedicated research with disaggregated data to highlight potential relationships between violence and the health of South Asians in the US [26]. According to a report published by a coalition of South Asian American organizations, 73% of South Asians reported being questioned about their national origin and 66% about their religious affiliations [27]. Additionally, South Asians whom government officials questioned could be pressured to spy on fellow community members. As a result of the fear of being racially targeted, many South Asians altered their behavior and social interactions to avoid additional investigations [28,29].

Nationally, almost half of South Asians reported experiencing discrimination in institutional settings (46% vs. 22% among whites). Healthcare discrimination is another significant issue among South Asians. Almost a fifth of South Asians reported experiencing unfair treatment when going to a doctor or health clinic; with some saying they avoided the doctor or healthcare due to concerns about receiving unfair treatment. While hate violence primarily focuses on physical and verbal assault, discrimination more broadly refers to unfair treatment of individuals based in whole or part on race, ethnicity, skin color, religion, national origin, and other identities. These include experiences anchored in false stereotypes of “terrorist” or “perpetual foreigner,” as evidenced by higher rates of racial slurs (36% among South Asians vs. 23% among whites) and harassment (22% among South Asians vs. 16% among whites) [28].

The model minority myth and the persistent lack of disaggregated data on Asian Americans perpetuate the exclusion of access to funding and resources to examine the health status of AA subgroups, including SAs. However, evidence to date suggests that these experiences of hate and violence significantly impact the physical and mental health, health behaviors, and healthcare utilization of South Asians in the US via multiple mechanisms [28].

Diabetes

Multiple risk factors contribute to pre-diabetes and diabetes among SAs in the US, including genetic predisposition, suboptimal dietary habits, lack of regular physical activity, insulin resistance, and visceral adiposity [30]. Acculturation and socio-religious beliefs also influence dietary choices and physical activity levels. South Asians were 3.4 times more susceptible to type 2 diabetes and had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes at a lower BMI and younger age than the white population [30,31].

South Asians have a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes at a lower BMI when compared to other ethnic groups [32]. Evidence shows the prevalence of type 2 diabetes among SAs in the United States was 27% when compared to 8% non-Hispanic white individuals [33]. MASALA study findings indicated that SAs have an increased deposition of ectopic fat, insulin resistance and insulin secretion impairment. Dietary habits with increased red meat, animal proteins, high-fat dairy products, fried snacks, and sweets are associated with cardio metabolic disease risk [34]. There is a significant association between a healthy plant-based diet and cardio-metabolic risks among SAs. Statistics indicated that the risk of type 2 diabetes was lowered by 18% for each 5-unit healthy plant-based diet score [35]. Preventive interventions focusing on health-related cultural factors and complete mechanistic pathways are essential to prevent type 2 diabetes among SA. Further research has been warranted to compare and understand the health habits and practices of second and third-generation SAs [30].

A study using the data from MASALA and MESA cohorts explored the relationship between body composition and the higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes among SA living in the United States. This study could not determine an association between body composition and type 2 diabetes prevalence among SA. Recommendations for future studies using MASALA and MESA cohorts are required to assess the impact of adipose tissue on glycemic impairment [36]. A cross-sectional analysis identified that South Asian immigrants had an increased prevalence of hypertension than European immigrants and whites [37].

Cardiovascular disease

Studies indicate a higher prevalence rate of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) risk factors among SA immigrants [38,39]. The US cholesterol treatment has specific guidelines for those from SA ancestry due to the high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [40,41]. One of the reviews reported that the increased cardiovascular risk factors and mortality rate found among SA immigrants had a complex association with immigration and their length of stay in the US [42].

The Mediators of Atherosclerosis in SAs Living in America (MASALA) study performed among 849 SA participants (45.8% women) examined acculturation strategies focusing on glycemic indices, blood pressure, lipid parameters, and body composition. The participants were placed in acculturation classes of separation (prefer SA culture), assimilation (prefer US culture), and integration (similar preference for both cultures). The study revealed no significant association between acculturation strategies and cardio-metabolic risk in SA men. This study suggests the need for culturally tailored programs based on acculturation strategy and sex to prevent and manage CVD risk factors among SA immigrants [43].

A 10-year follow-up retrospective cohort study in Northern California showed that 8.93% of SA patients had cardiovascular death, percutaneous or surgical revascularization, or myocardial infarction. In contrast, the incidence was 5.66% among the other racial-ethnic groups included in the study [44]. Studies confirm that SAs develop severe CAD at a younger age than other populations, resulting in increased mortality and morbidity [39].

Conclusion

This review sheds light on the health disparity among the SA population in the United States. Lower colorectal cancer, obesity, hypertension, violence, discrimination, pre-diabetes and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health were the major themes explored in this review. Multiple factors influence the health disparity among the SA population, including genetics, environmental, cultural, structural, dietary patterns, acculturation, and socio-religious factors. Engaging culturally responsive healthcare workers, providers, and community members is crucial to address these issues. Further studies are highly recommended to help develop culturally tailored intervention programs, including preventive and management strategies to effectively tackle the identified health disparities considering the social determinants of health factors.

References

- Budiman A, Cilluffo A, Ruiz NG. Key facts about Asian origin groups in the US. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. 2019.

- Karasz A, Gany F, Escobar J, et al. Mental health and stress among South Asians. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:7-14.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samuel E. Acculturative stress: South Asian immigrant women's experiences in Canada's Atlantic provinces. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2009;7(1):16-34.

[Crossref]

- Bhattacharya G, Schoppelrey SL. Preimmigration beliefs of life success, postimmigration experiences, and acculturative stress: South Asian immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Health. 2004;6: 83-92.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inman AG, Howard EE, Beaumont RL, et al. Cultural transmission: Influence of contextual factors in Asian Indian immigrant parents' experiences. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(1):93.

- Kaduvettoor-Davidson A, Inman AG. South Asian Americans: Perceived discrimination, stress, and well-being. Asian Am J Psychol. 2013;4(3):155.

[Crossref]

- Inman AG. South Asian women: Identities and conflicts. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12(2):306.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao A, Ahmed T, Islam N. Community health needs and resource assessment: An exploratory study of South Asians in NYC. Community Health Needs and Resource Assessment. 2007:1-34.

- Glenn BA, Chawla N, Surani Z, et al. Rates and sociodemographic correlates of cancer screening among South Asians. J Community Health. 2009;34:113-21.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong ST, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, et al. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening rates among Asian Americans and non-Latino whites. Cancer. 2005;104(S12):2940-7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- King L, Deng W. Health Disparities among Asian New Yorkers. Epi Data Brief (100). New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York City. 2018.

- Rastogi N, Xia Y, Inadomi JM, et al. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening in New York City: An analysis of the 2014 NYC Community Health Survey. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2572-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manne S, Steinberg MB, Delnevo C, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among foreign-born South Asians in the metropolitan New York/New Jersey region. J Community Health. 2015;40:1075-83.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menon U, Szalacha L, Prabhughate A, et al. Correlates of colorectal cancer screening among South Asian immigrants in the United States. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(1):E19-27.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel S, Kranick J, Manne S, et al. A population health equity approach reveals persisting disparities in colorectal cancer screening in New York city south asian communities. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36:804-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gray LJ, Yates T, Davies MJ, et al. Defining obesity cut-off points for migrant South Asians. PloS One. 2011;6(10):e26464.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misra A. Ethnic-specific criteria for classification of body mass index: a perspective for Asian Indians and American Diabetes Association position statement. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(9):667-71.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misra A, Jayawardena R, Anoop S. Obesity in South Asia: phenotype, morbidities, and mitigation. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8:43-52.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran S, Wyngaard JC. Subfilter-scale modelling using transport equations: Large-eddy simulation of the moderately convective atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary Layer Meteorol. 2011;139:1-35.

- Neupane D, McLachlan CS, Sharma R, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in member countries of South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2014;93(13).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hossain FB, Adhikary G, Chowdhury AB, et al. Association between Body Mass Index (BMI) and hypertension in south Asian population: Evidence from nationally-representative surveys. Clin Hypertens. 2019;25(1):1-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta R, Gaur K, Ram CVS. Emerging trends in hypertension epidemiology in India. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(8):575-87.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geldsetzer P, Manne-Goehler J, Theilmann M, et al. Diabetes and hypertension in India: A nationally representative study of 1.3 million adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):363-72.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hills AP, Arena R, Khunti K, et al. Epidemiology and determinants of type 2 diabetes in south Asia. Lancet Diabetes Endocrino. 2018;6(12):966-78.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linderman GC, Lu J, Lu Y, et al. Association of body mass index with blood pressure among 1.7 million Chinese adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181271.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misra S, Tankasala N, Yusuf Y, et al. Health implications of racialized state violence against south Asians in the USA. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(1):1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drum. “In Our Own Words: Narratives of South Asian New Yorkers affected by racial and religious profling,” Mar. 2012. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2021.

- McMurtry CL, Findling MG, Casey LS, et al. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Asian Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:1419-30.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan K, Wong J, Lee J, et al. 2016 post-election national asian american survey. Riverside, Calif: National Asian American survey. Accessed November. 2017;4:2020.

- Gujral UP, Kanaya AM. Epidemiology of diabetes among South Asians in the United States: lessons from the MASALA study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1495(1):24-39.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiu M, Austin PC, Manuel DG, et al. Deriving ethnic-specific BMI cutoff points for assessing diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1741-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Narayan KV, Kanaya AM. Why are South Asians prone to type 2 diabetes? A hypothesis based on underexplored pathways. Diabetologia. 2020;63(6):1103-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2389-98.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gadgil MD, Anderson CA, Kandula NR, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic risk factors in South Asians living in the United States. J Nutr. 2015;145(6):1211-7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhupathiraju SN, Sawicki CM, Goon S, et al. A healthy plant–based diet is favorably associated with cardio-metabolic risk factors among participants of South Asian ancestry. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;116(4):1078-90.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flowers E, Lin F, Kandula NR, et al. Body composition and diabetes risk in South Asians: Findings from the MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):946–53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Commodore-Mensah Y, Selvin E, Aboagye J, et al. Hypertension, overweight/obesity, and diabetes among immigrants in the United States: An analysis of the 2010-2016 National health interview survey. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1-0.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, et al. Understanding the high prevalence of diabetes in US south Asians compared with four racial/ethnic groups: The MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes Care. 2014 ;37(6):1621-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Volgman AS, Palaniappan LS, Aggarwal NT, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138(1):e1-34.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalra D, Vijayaraghavan K, Sikand G, et al. Prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the US: A clinical perspective from the national lipid association. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15(3):402-22.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makshood M, Post WS, Kanaya AM. Lipids in South Asians: Epidemiology and management. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2019;13:1-1.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guadamuz JS, Kapoor K, Lazo M, et al. Understanding immigration as a social determinant of health: Cardiovascular disease in Hispanics/Latinos and South Asians in the United States. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021 ;23:1-2.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Sofiani ME, Langan S, Kanaya AM, et al. The relationship of acculturation to cardiovascular disease risk factors among US South Asians: Findings from the MASALA study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;161:108052.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pursnani S, Merchant M. South Asian ethnicity as a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2020 ;315:126-30.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]