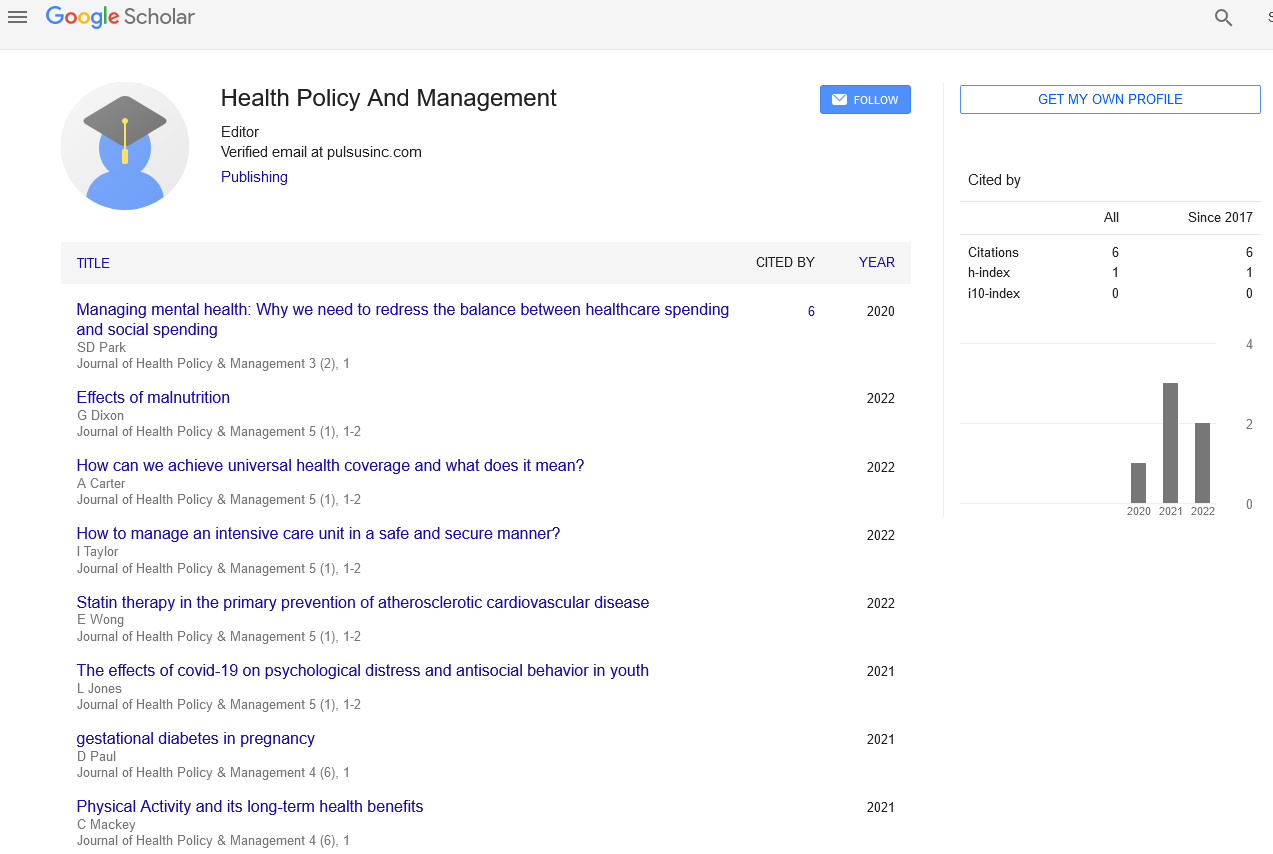

How can we achieve universal health coverage and what does it mean?

Received: 07-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. PULHPM-22-4129; Editor assigned: 09-Jan-2022, Pre QC No. PULHPM-22-4129 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jan-2022 QC No. PULHPM-22-4129; Revised: 21-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. PULHPM-22-4129(R); Published: 28-Jan-2022, DOI: 10.37532/pulhpm.22.5(1).1-2

Citation: Carter A. How can we achieve universal health coverage and what does it mean? J Health Pol Manage. 2022;5(1):1-2.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

How could we keep people healthy and safe, no matter where they live? Universal health coverage (UHC) has received the most political attention of all global health programmes. But, as vital as it is, can Universal health Care possibly meet the two core goals of the right to health: keeping people healthy and safe while leaving no one behind? There is a universal need for health and safety, as well as a fundamental conviction in justice and equity. Is it possible for UHC to accomplish both health and equity, or “global health with justice,” as I call it? What factors contribute to a population’s health and safety? Universal and affordable access to healthcare, including clinical prevention, treatment, and needed drugs, is unquestionably necessary. Public health services, such as monitoring, clean air, and drinking water, go beyond medical care. Social factors, such as housing, work, education, and equity, are the final and most crucial component in good health. It would substantially improve global health if we could supply everyone with these three fundamental conditions for optimal health (healthcare, public health, and social determinants). But we must also take steps to ensure that no one is left behind. We must plan for equity in order to accomplish it, and here I suggest national health equity action initiatives. The highest responsibility of society is to attain global health in a just manner.

Keywords

Universal health coverage; Sustainable development goals; Health policy; Management

Introduction

The concept of universal health care is quite popular in politics. All UN Member States approved the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, with a single health goal: “Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages [1]. Its most significant goal is to attain universal health coverage by 2030. All roads lead to UHC,” declared World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Distributed due Adhanom, who has made universal coverage WHO’s top objective [2]. Last October, the United Nations General Assembly unanimously endorsed “UHC: Moving Together to Build a Healthier World,” a landmark political declaration [3]. Such political commitment is required since achieving the SDG target on UHC is both ambitious and necessary: In 2017, just around half of the world’s population had access to basic services. Strong and capable health systems are critical for good health, but what does the international community mean when it talks about universal health coverage? In fact, UHC definitions are inconsistent, which is concerning [4]. Financial risk protection is emphasised by the UN, WHO, and World Bank, which means that healthcare costs should not push people into poverty. Although this is a worthy goal, UHC definitions are actually extremely restrictive. Despite the fact that other components of the SDGs cover a wide variety of public health tasks, UHC is limited to medical and nursing care: “access to excellent essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, high-quality, and affordable necessary medications and vaccinations for everyone [5]. The World Bank’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) concept similarly emphasises healthcare, emphasising that health services support a country’s strongest sectors. The WHO has a broader definition of UHC, which includes both prevention and treatment, and states that everyone should be able to “employ the promotive, preventative, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health care that they require [6]. Importantly, the WHO and the Bank collaborate to monitor UHC implementation, which includes sanitation, non-communicable diseases (such as diabetes, heart disease, and tobacco control), and health security, as defined by the WHO (preparedness for fast-moving epidemic diseases) [7]. Although this broader definition of UHC is commendable, WHO rarely advocates for population-based public health services as part of the UHC package. That is, WHO does not place a high emphasis on a strong public health infrastructure in its policy, lobbying, or spending?

What are the important determinants of health and well-being if the ultimate goal of UHC is to achieve healthier, safer populations? Of course, healthcare is crucial. Everyone needs access to reasonable diagnostic, treatment, and rehabilitation services, as well as emergency and palliative care. Medical care, on the other hand, is only a minor part of what makes a people healthy. Public health services, which include clean air, safe drinking water, vector control, injury prevention, and tobacco and alcohol control, are more vital. People thrive when they live, work, and play in circumstances that promote physical activity (walking, biking, and recreation) and a healthy diet (fresh fruits, vegetables, lean protein). To summarise, the environment in which we live has a significant impact on our health. The natural and physical settings in which we live must be protected be beneficial to one’s health our built environment must be designed in such a way that health becomes the “easier option.” And, as essential as healthcare and public health are, the truth is that the services and opportunities available outside the health sector have the greatest impact on people’s health. Income, education, housing, social support, and gender/racial equality are all social determinants of health [8]. That is why health necessitates a “whole-of-government” approach, in which all ministries include health in their policies, procedures, and funding.

Discussion

People’s health is influenced not only by the services they have access to and the places they live in. Equity is also necessary for good health. Large differences in income, education, and social status are associated with populations that are less healthy overall. Consider the situation in the United States, where, after decades of steady development, life expectancy has been declining over the past three years [9]. The majority of deaths are due to so-called “diseases of despair,” such as alcohol and drug (opioid) addictions, depression, and suicides. Furthermore, the poor and middle classes have a disproportionate share of the burden of early mortality, since they have fallen further behind while the wealthy have become even wealthier. As a result, all countries should create, fund, and implement national health equity action plans-systematic, systemic, and inclusive methods to achieving health equity. Seven fundamental principles for health equity action programmes were identified by an international group of scholars and campaigners. Programs of action should be developed through inclusive, participatory, and empowering processes; have the explicit goal of maximising health equity; encompass both the health sector and other sectors, including the full range of social, environmental, economic, commercial, and political determinants of health; comprehensively identify all populations experiencing health inequities, analysing their specific obstacles to good health, and identifying actions to overcome them; and have the explicit goal of maximising health equity incorporate accountability measures; and be backed by long-term high level political commitment, including leadership from heads of government. Only by measuring who is left behind and why, as well as taking specific steps to promote health equity, can the health disparity gap be considerably decreased? [10].

The term “legal determinants of health” was coined by a Lancet Commission on Global Health and the Legislation in 2019 to demonstrate how law can be a significant tool for safeguarding the public’s health and safety. This technology must be put to good use in order to promote health and human rights. For example, criminal legislation targeting HIV/AIDS patients, regulations restricting sexual and reproductive health services, and criminalization of the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) community can all be barriers to good health. Whatever definition is used, UHC can only be achieved through legislation. The Legal Solutions for UHC Network was launched at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019 by WHO, the United Nations Development Programme, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the InterParliamentary Union, and the O’Neill Institute at Georgetown University to support national law reform [11]. To achieve UHC, three key legislative determinants of health are required: (1) All fundamental elements of UHC must be met by health laws; (2) health systems must be well-governed; and (3) public authorities must follow the law. We also require high-quality data, particularly data on sub-populations. It is hard to assess health inequalities without first determining who is left behind and whether programmes aimed at eliminating them are effective. The only way to bridge the health equality gap is to collect granular data on health outcomes and then act on it.

Adherence to five essential ideals is required to advance the right to health through UHC. Universally accessible, equitable, cheap, high-quality, and costeffective health care are required. Everyone in the country should be eligible for the entire range of health services, medicines, and immunizations under a comprehensive national health law. No one should be left out, regardless of their income, gender, colour, legal status, or other factors. Coverage of illegal residents and migrants is very contentious in many nations, and most governments do not provide complete (or even partial) coverage to these groups [12]. However, denying migrant’s full access to the health system will undoubtedly jeopardise the SDG goal of universal health coverage. Furthermore, there should be no unique health-care eligibility restrictions, such as age. Equity is the next value of a healthy health system. UHC must be both universal and equitable. Many countries claim to provide universal coverage, but certain populations, such as those living in rural areas, receive worse care. To give another example, in certain nations, health regulations provide various health benefits based on the insurance arrangement, which is inequitable. The services provided in low-income areas are frequently of lesser quality than those provided in high-income areas. One of the many causes for inequitable health service distribution is that professional health personnel are disproportionately concentrated in high-income urban areas, while being scarce in poorer, more rural areas. Every individual is entitled to a nearly equal range of services of consistently excellent quality. Affording the letter and spirit of UHC are violated when certain areas receive fewer services or of lower quality. Governments can provide resources more equally across populations and geographic areas by establishing robust public health regulations.

Health services for all are useless unless they are of consistently high quality. Pharmaceuticals are safe and effective, physicians are properly qualified, hospitals satisfy certification standards, and health facilities avoid medical errors or hospital-acquired infections, for example, thanks to laws and regulations. We often overlook the value of high-quality services in the quest for universal coverage, yet quality is critical. Poor quality treatment was responsible for more than 5 million-and probably 8 million or more-deaths in low- and middle-income countries in 2015 [13].

Conclusion

There are additional needs for ensuring healthy populations, even if national health laws sufficiently satisfy these five essential objectives. Health-care systems must be well-run. Evidence-based targets, monitoring and assessing outcomes, inclusive engagement, transparency, honesty, and accountability are all required for good governance. Without a thorough evaluation of outcomes based on complete openness, it is impossible to tell if health systems are serving population needs. Good stewardship of health resources is required of public leaders, health personnel, and hospitals. As a result, proactive waste and corruption-fighting measures are required. There must also be processes in place to hold people accountable for achieving essential health-care goals. While many people consider UHC to be just a scientific and technological endeavour, strong law and governance are critical for the health and safety of people everywhere. Furthermore, the law must ensure that all of the conditions necessary for excellent health and well-being are met, including high-quality healthcare, public health, and social determinants of health. Of course, law is not the only tool for achieving global health through justice, but it is the most potent.

REFERENCES

- Loughnan L, Mahon T, Goddard S, et al. Monitoring menstrual health in the sustainable development goals. Palgrave Handb Crit Menstruation Stud. 2020:577-592.

Google Scholar - Ghebreyesus TA. All roads lead to universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):839-840.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Sparkes SP, Kutzin J. HIV prevention and care as part of universal health coverage. WHO. 2020;98(2):80.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Gostin LO. The legal determinants of health: How can we achieve universal health coverage and what does it mean? Intern J Health Pol Manage. 2021;10(1):1.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - World Health Organization. Nutrition in universal health coverage. WHO; 2019.

Google Scholar - World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage. Global monitoring Rep. 2017.

Google Scholar - Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States. Jama. 2019;322(20):1996-2016.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Friedman EA, Gostin LO, Kavanagh MM, et al. Putting health equity at heart of universal coverage-the need for national programmes of action. BMJ. 2019;367.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Gostin LO, Monahan JT, Kaldor J, et al. The legal determinants of health: harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. The Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1857-1910.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Gostin LO. The legal determinants of health: How can we achieve universal health coverage and what does it mean? Intern J Health Pol Manage. 2021;10(1):1.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Gostin LO. Is affording undocumented immigrants health coverage a radical proposal? JAMA. 2019;322(15):1438-1439.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - Gostin LO, Abubakar I, Guerra R, et al. WHO takes action to promote the health of refugees and migrants. The Lancet. 2019;393(10185):2016-2018.

Google Scholar Cross Ref - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Crossing the global quality chasm: Improving health care worldwide.

Google Scholar