Human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers at a South African rural district hospital during COVID-19 pandemic

2 Department of Advance Nursing Science, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa

3 Department of Health Studies, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, South Africa

4 Department of Health Studies, University of South Africa, South Africa

5 Department of Nursing Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa

6 Department of Health Studies, University of South Africa, South Africa

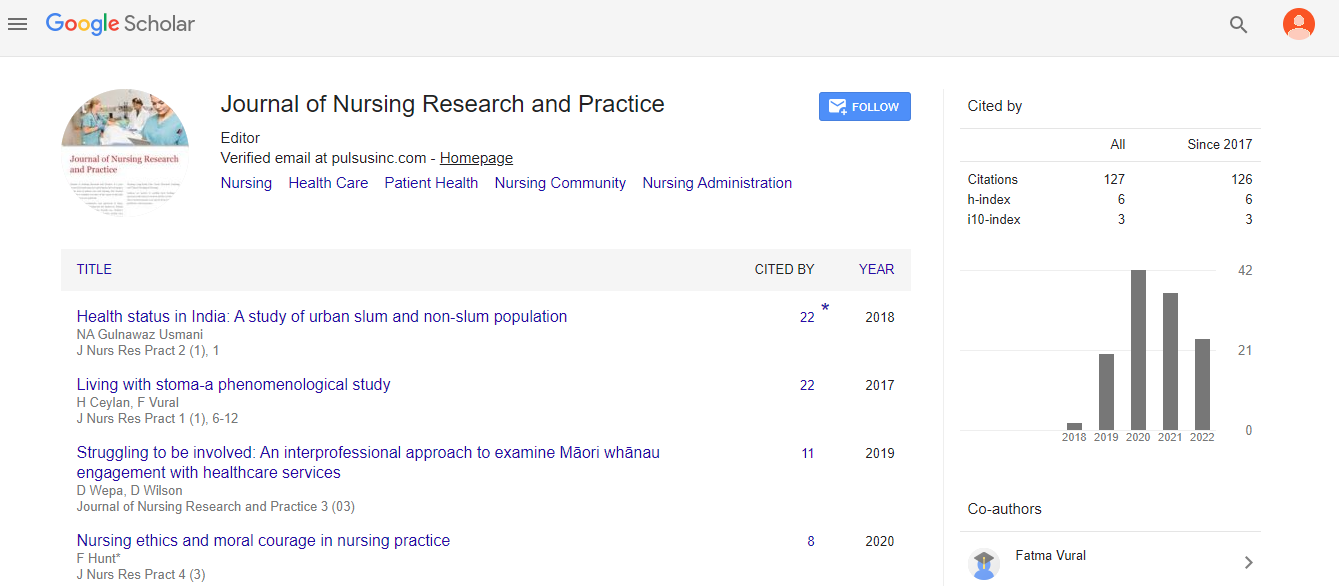

Received: 12-Jul-2021 Accepted Date: Jul 23, 2021; Published: 30-Jul-2021, DOI: 10.37532/2632-251X.2021.5(7).88

Citation: Tshivhase L, Ndou ND, Risenga PR, et al. Human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers at a South African rural district hospital during COVID-19 pandemic. J Nurs Res Prac. 2021; 5[7]:1-6.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: The Coronavirus disease of 2019 [COVID-19] has drastically transformed the health care system. People are infected almost every day with COVID-19. Some of the people infected end up in the hospitals leading to overcrowding of the wards. Thus, the nurse managers are expected to ensure that the hospital and wards are well managed. The situation may be worse in rural hospitals where the resources are limited.

Aim: This study explored the human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers during the COVID19 pandemic, in the district hospital of Vhembe, Limpopo Province.

Method: The researchers followed a descriptive phenomenological approach. Data were collected through telephonic in-depth individual interviews from seven purposively selected nurse managers. Data analysis followed the seven procedural steps by Colaizzi.

Results: Results indicate that nurse managers had to deal with staff shortages on a daily basis. The staff shortage resulted from absenteeism due to COVID-19 infection or COVID-19 infected family members at home. Shortage of staff was also worsened by early retirement, resignation or death of nurses. The nurse managers ensured that the hospital remains functional by devicing means of curbing the shortage through provision of COVID-19 centred management and flexible allocation.

Conclusion: The study findings highlighted that managers has to deal with staff shortage on daily basis. The shortage seems to be worsening. The situation highlights the urgent need of improving staffing at the hospital and supporting available nurses in rural public hospitals to ensure that they continue to provide services. There is need for providing incentives for the nurses who are continuously risking their lives in ensuring that patients with COVID-19 receive care. This revealed a need for the government to provide continuous support to nurse managers, more specifically during a pandemic like COVID-19.

Keywords

Nurse managers; Human resource challenges; COVID-19 Pandemic; Rural district hospital

Introduction and Background

The Coronavirus disease of 2019 [COVID-19] is acknowledged by scientists as caused by SARS-CoV-2 that can trigger respiratory tract infection [1]. Currently, there is enormous demand for managing the COVID-19 outbreak, which challenges both health care personnel and the medical supply system. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented change in health care systems. Nurse managers are providing leadership to nurses caring for patients during a catastrophe. They are responsible for developing the risk response plans for COVID-19 [2,3].

Due to the seriousness of the disease outbreak, nurse managers had different experiences related to human and material resources. As the frontline of our health care system, nurse managers are responders as COVID-19 moved through our community with fewer material resources. Nurses had been working tirelessly to care for sick and dying patients, at the same time exposing themselves and their families to the virus [4]. The nurses’ anxiety levels were rising as they heard not just about medical workers infected in other hospitals falling sick, but now an increasing number of their own colleagues as well [5].

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the workload in the roles and functions of nurse managers responsible for patient care. The pandemic has increased the challenges experienced by nurse managers in the patient health care system [6,7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurse managers experienced subjective stress, increased concern about the future and an increased workload. These nurse managers are working under stressful circumstances [8]. The challenges brought about by the pandemic have added significantly to the burden of already strained and vulnerable nurse managers. They will likely contribute to increased burnout, high staff turnover and staff shortages in the long term [8].

Nurse managers were worried about their staff, their health and burnout, however, the worry was bottled up inside to absorb all the nurses’ concerns. The study by White [9] reported that nurse managers did not seek help regarding their concerns, but instead decided to carry the burden alone.

The South African health care system is currently overwhelmed by the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse managers are challenged by having to work in a totally new context; suffering exhaustion due to heavy workloads, having to wear protective gear, fearing infection and infecting others, feeling powerless to handle patients’ conditions, and managing relationships in this stressful situation. The exhaustive work shattered health care nurse managers physically and emotionally, but also showed their flexibility and professional dedication in overcoming challenges [10].

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced nurse managers to face new challenges such as stigmatization and risk of being infected and infecting their family members too. Furthermore, as a result of fear to contract the Coronavirus, they may lack engagement with patients, staff and nurse managers themselves [10]. When the hospitals faced an influx of COVID-19 patients, they had to increase their bed capacity, but they may also lack trained nurses to staff those areas. Nursing managers are then compelled to develop more practical strategies to address the challenges of a shortage of human resources and material resources [11]. Heckers [12] suggested seven ways in which hospitals and the states can cope with nursing shortages during Coronavirus patients’ surge. Among the ways suggested, is for nurses to have access to protective equipment to prevent them from contracting the disease, as illness could worsen staff shortage. Another one is about students who are about to graduate that could also help hospitals during the pandemic [12]. However, the rural hospitals, in impoverished environment, with limited resources, such as Vhembe district, the situation may be different from the urban based hospitals. That make the researcher raised the following question: What are the human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers at a South African rural district hospital during COVID-19 pandemic? Therefore, this study sought to explore the human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic at a district hospital in Vhembe of Limpopo province South Africa.

Methods

Design

A qualitative descriptive phenomenological design was used to explore and describe the human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers in a South African rural district hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. The researcher followed a descriptive phenomenological design to describe the nurse manager’s world and make sense of the manager’s perceptions of the world from participants’ viewpoints [13]. A descriptive phenomenological study was undertaken with the aim of looking at the phenomenon to be studied through the eyes of those who have experienced it [14]. In phenomenological studies, it is believed that critical truth about reality is grounded in people’s lived experiences [15]. Nurse managers are responsible for planning, organizing, leading and controlling in their health care management work, and therefore, the researcher believes they could meaningfully share lived experiences from their own perspective [15,16]. A descriptive phenomenological design was suitable to explore the experiences of nurse managers in the context of their working environment during the COVID-19 period. The COVID-19 pandemic was a new phenomenon globally and also to South African hospitals as it was never researched.

Setting, population, and sample

The study was conducted in the rural district hospital of Vhembe in Limpopo Province, South Africa. This hospital like others in the province was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The hospital experienced high rates of infections and deaths among employees during the COVID-19 era. Population for the study was all the nurse managers of the district hospital of Vhembe in Limpopo Province. The total nurse managers for the district hospital were estimated to be 14 in number by the hospital chief executive officer.

Recruitment of participants was done telephonically through a purposive sampling of one nurse manager who, after having consented to the study, provided contact details of other nurse managers in the hospital who fitted the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for nurse managers were those who had been managing their wards for three or more years and have consented to participate in the study. Other nurse managers were also recruited telephonically by the third author after getting their phone number from the first participant. The researcher reached saturation after interviewing seven nurse managers and stopped interviewing as there was a redundancy of previously collected data [17]. The sample size was, therefore, seven and this was justified as being adequate by Polit and Beck [15], who iterated that in descriptive phenomenological studies, saturation can be achieved with ten or fewer participants. Additionally, Ellis [18] suggested that 6–20 participants are sufficient for descriptive phenomenological studies. Table 1 presents the biographical data of participants. Pseudonyms were used and their ages were presented in ranges to protect the participant’s identity.

Pretesting

Interview guide was developed by the researchers to guide the interviews for this study. The interview questions were pretested on two nurse manager’s prior actual data collection. Pretesting was done to assess the practicalities of the main studies as well as time and cost to conduct the main study [19]. The interviews were audio recorded and then listened to by the reseachers. There were no flaws found as participants were able to respond well to the questions of the interviews. The researchers were all satisfied with the results of the interview guide and it was then finalised for use in the main study.

Data collection

Arrangement to collect data was made with the first nurse manager, who consented to be interviewed. The interviews were scheduled for lunch hours when the participants were available. The consent forms were e-mailed to participants for signature. Consent was also given verbally before the interviews were conducted. The researcher collected data through in-depth individual telephonic interviews using a developed interview guide due to COVID-19 restrictions. The in-depth individual interview was used to allow the researcher to probe the responses given and gain a richer understanding of how the participant sees the world. Open-ended questions were used to direct the interview [21]. One central question was posed: “Kindly share with me your experiences as a nurse manager during the COVID-19 pandemic? The central question was followed by short probes such as” How did you manage the wards? H did you address the challenges? More probes were developed based on the nurse managers’ responses.

The participants were interviewed for 45-60 minutes. Researchers one, two, and three participated in the interviews. The research team reviewed the interviews for the fullness of information and variations. The researchers used intuition, bracketing, analyzing, and evaluation during data collection. The researchers used the reflexive journal to bracket their feelings and opinions during the interviews. During the interviews, the researcher would pause to allow recording of the tone of voice and silence as field notes supporting the audio-recorded interviews [21]. Data was collected and recorded until saturation at participant number seven [7]. The first author then transcribed the audio recordings.

Data analysis

To discover, communicate, bring order and make sense of the data collected, the first and third authors analyzed the collected data by first reading the interview transcripts to establish the crucial messages that emerged [15]. Emerging themes were grouped in a meaningful way. Raw data was reduced to be more manageable. Important ideas were filtered out from the less significant themes were identified. A narrative account of the analysis was constructed. An independent coder was also used to analyze the data and check the essence of the message as described by Ellis [18]. The themes that emerged were supported by the quotes from the participants. A table of themes was arranged following data analysis (Table 2).

Measures to ensure trustworthiness

Measures to ensure the trustworthiness of the study were assessed for credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability. Credibility was ensured by having prolonged telephonic conversations with the participants as well as recording the verbatim quotes. Transferability was ensured by a detailed description of the background information of participants and the setting for the study. The researchers ensured dependability by describing the methods and comparing field notes with voice recordings. Verification of data against the recorded responses was done in concluding the study findings. Confirmability was ensured by involving a different researcher during data collection and data analysis to verify interpretations, data verification recommendations and conclusions. Clear descriptions of each stage of the research process, explaining and justifying what was done, by voice recording, and the verbal quotes recorded during the unstructured individual interviews are all evidence to the independent co-coder during the data analysis process to ensure authenticity [15,20,22,23].

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was received from the Ethics Committee of the University of South Africa [Ethical clearance number: Reference #: 90187598_CREC_CHS_2021] Permission to conduct the research study was also obtained from the Department of Health, Limpopo Province, Vhembe district Primary Health Care office and the Vhembe district hospital Chief Executive Officer. Confidentiality was ensured by using pseudo names; age was concealed by using the age range rather than exact age and years in nursing and nursing management. The name of the hospital was not mentioned. Ethical principles such as voluntary participation, withdrawal, and respect for autonomy, beneficence, privacy, confidentiality, justice and informed consent were adhered to [17].

Results

This section presents the biographical data of participants (Table 1). The findings of the of the study are presented and described with the incerpts from the participants and controlled by the related literature.

| Name | Gender | Age | Number of years in nursing | Number of years as manager | Training in COVID-19 management | Professional nurse training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 Mulatwa | Female | 40–45 | 10–15 | 6–10 years | Orientation | Four-year Diploma |

| P2 Mushoni |

Female | 56–60 | 15–20 | 6–10 years | Orientation | Bridging |

| P3 Mushai |

Female | 56–60 | 36–40 | 11–15 | Orientation | General Nursing |

| P4 Muhangwi |

Female | 50–55 | 20–25 | 6–10 | Orientation | Four-year Diploma |

| P5 Maemu |

Female | 46–50 | 15–20 | 6–10 | Orientation | Bridging |

| P6 Malindi |

Female | 60–65 | 31–35 | 10–15 | Orientation | Four-year Diploma |

| P7 Khakhathi |

Male | 50–55 | 31–35 | 11–15 | Orientation | General Nursing |

Table 1: Characteristics of participants.

Seven nurse managers between the ages of 40–65 years participated in this study. The participants comprised six females and one male nurse manager. All the study participants had more than six years of management experience. Their nursing experience was between 10–40 years, and they were orientated on COVID-19 management.

Experiences of the nurse managers during COVID-19 pandemic

The results presented are based on the analysis of data collected from the participants. Two superordinate themes with several themes and subthemes are presented in Table 2.

| Superordinate themes | Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Shortage of staff | Absenteeism | Quarantine, waiting for COVID-19 results |

| Off sick following testing positive for COVID-19 | ||

| Prolonged sick leave due to COVID-19 related complications | ||

| Faking being sick due to fear of infection | ||

| Family responsibilities induced by COVID-19 related sickness or death | ||

| Attrition of staff | Resignation | |

| Retirement | ||

| Deaths | ||

| Ways for curbing shortage of manpower |

COVID-19 centred management | Properly staffing of COVID-19 ward |

| Converting chronic wards into COVID-19 wards | ||

| Combining wards | ||

| Admitting only critically ill patients | ||

| Flexible staff allocation | Reshuffling of staff | |

| Centralised daily allocation | ||

| Nurses working overtime |

Table 2: Summary of themes that emerged from data analysis.

Shortage of staff

This superordinate theme focuses on the staff shortage experienced by managers at the rural district hospital. It is composed of two themes, namely, absenteeism and attrition of staff.

Theme 1 Absenteeism

Participants raised absenteeism as one of the major challenges that the nurse managers have to deal with daily. They raised several causes of absenteeism that occurred during the COVID-19 lockdown. These include quarantine while waiting for COVID-19 results, off sick following positive test for COVID-19, prolonged sick leave due to COVID-19 related complications, family responsibilities induced by COVID-19 related sickness or death, and faking being sick due to fear of infection.

Quarantine while waiting for COVID-19 results

This subtheme focuses on the absenteeism caused when staff in the wards is expected to stay at home while waiting for the COVID-19 test result. Participants mentioned that hospital staffs, especially nurses who are frontline workers when it comes to COVID-19, are frequently tested for COVID-19.

“During the second wave of COVID-19, some nurses were absenting themselves to go for testing. They were doing regular testing. They knew that, if they have tested, they should go home until the results are out” [Malindi]

The testing was mostly used as an excuse for not coming to work, as indicated by Khakhathi in the following quotation:

“There was a severe shortage in the wards because everyone wanted to test and they had to be quarantined for a few days before getting their test results.”

Unfortunately, some of the test results ended up being COVID-19 positive, which prolonged absenteeism, as now the staff member would be off sick for a longer time.

Off sick following testing positive for COVID-19

This subtheme focuses on absenteeism resulting from staff testing positive for COVID-19. Participants mentioned that, for those staff that tested COVID-19 positive, they would be expected to stay at home for at least ten days whether they have physical symptoms or not. This prolonged absenteeism increased staff shortage, as indicated by the following quotation from the participants:

“We are experiencing a shortage of staff, nurses, doctors, and general workers because they are getting infected and some complicate and end up getting admitted. There was also a huge shortage of general workers because they tested positive and they had to quarantine at home for the full fourteen days.” [Mulatwa]

“It is very tough because there are no nurses and drivers are sick due to COVID-19. You come in the morning and you hear from others that so and so are sick. Others call and tell you that they are not feeling well and they are booked off by their doctors. There is a shortage of drivers as well due to ill-health and we had no one to collect emergency blood for us.” [Mushoni]

Though some staff members were absent because of COVID-19 infection, some nurses fake illnesses and absent them from work, thus, the following subtheme focusing on faking illness.

Faking illness

Participants express that some staff members decide to stay at home even though they are not sick. However, to cover themselves, they will come with a sick note or wait for the manager to make a follow-up regarding their whereabouts and then produce sick notes.

Some just decide to buy sick notes from the local doctors because they fear getting infected by COVID-19. [Mushai]

Mushai alluded to the fact that her unit was running short of general workers and nurses due to COVID-19 infection through the following quotations:

“Instead of coming to work, the nurse will just decide to go for testing, then come back with a sick note from the doctor. There was a shortage due to absenteeism because some nurses would just not report for duty, but when you make a follow-up, they will just give you a doctor’s sick note. We had a severe shortage of staff on top of the shortage we have.” [Mushai]

The shortage of nurses was also confirmed by the following quotations:

“Because people, more specifically nurses, were COVID-19 positive and had to be quarantined. Unfortunately, most of them did not recover, so they ended up taking many days off sick.” [Khakhathi]

The same shortage: “Nurses will leave work and go to test in private facilities using their medical aid. This will leave us with very few nurses in the ward and contribute to shortages, and they will come back with doctor’s sick notes saying they were booked off.” [Mushai]. A common challenge for all the nurse managers was a shortage of nurses due to nurses being infected with COVID-19. They would, thus, not report for duty and this affected patient care. Nurse managers went on to explain that other staff members would be absent, not because they were ill, but because they were taking care of family members who were sick, and the subtheme below addresses this.

Family responsibilities induced by COVID-19 related sickness or deaths

Staff members would stay home to look after family members who had tested positive for COVID-19 and that, sometimes as a nurse manager, you are scared to let them come to work fearing for the lives of others. This was affirmed by the following quotation:

“Some staff members could not come to work because they were taking care of their sick relatives at home and sometimes their close relatives tested positive for COVID-19, so they wouldn’t come to work because they are exposed and we could not insist, because it would mean infecting the whole ward with COVID-19 if we allow them to report for duty.” [Muhangwi]

Theme 2 Attrition of staff

Other issues that led to staff shortages, as experienced by nurse managers in the wards, were resignations, retirements and death of different staff members.

Resignations

Nurse Managers were also faced with continuous resignations of staff members. Most of the nurses who resigned were above the early retirement age of 55 years. The quotations below support this subtheme. “Majority of the nurses above 55 years is resigning and we have twelve who have resigned already. It is an increasing burden to us because we are short-staffed already.”[Mulatwa]

“Some nurses decided to resign due to fear of COVID-19 with immediate effects, without even serving notice due to fear of death. A person would just send a resignation letter, while we think that, she is coming back from sick leave.” Besides resignations, there were also retirements, as presented in the next subtheme.

Retirements

Another problem related to staff attrition, experienced by nurse managers, was staff retirement. This was indicated by the following excerpts from participants: “Most of the nurses are retiring, some are taking early retirement. This time, even general workers are seen retiring, which means there is a staff shortage for both nurses and general workers. It is very difficult because even cleaners have retired and this is increasing shortage of staff.” [Khakhathi]

“Some nurses decided to take early retirements due to fear of COVID-19. Most of the senior nurses who are above 55, opted for early retirement, mentioning that they do not want to die before enjoying their pension money. ”[Malindi].

Death

The other painful experience for nurse managers, which also aggravated the shortage of staff, was related to the death of staff members due to COVID-19 infection. The quotations below are in support of this subtheme.

“We lost colleagues. We lost our nurses. We lost pharmacists and general workers due to COVID-19 related deaths. Because some of them could not recover, they succumbed to death. Unfortunately, the staff shortage is increasing every day, but there is no replacement.” [Mushai]

“Death of a co-worker is the reason for staff shortage in the ward. We have two nurses who died because of COVID-19 in my ward and this has caused a serious shortage.”[Muhangwi]

Ways for curbing the shortage of staff

This superordinate theme focuses on ways for curbing the shortage of staff, which are, creating COVID-19 centered management and designing flexible staff allocation.

Theme 3 COVID-19 centered management

To curb staff shortages during COVID-19, nurse managers resorted to creating COVID-19 management. This theme focused on four subthemes: proper staffing of COVID-19 ward with the available staff members, converting some chronic wards into COVID-19 ward, combining wards, and admitting only critically ill patients.

Proper staffing of COVID-19 ward

Together with the hospital management, nurse managers tried to properly staff the COVID-19 wards even though there were severe staff shortages. The initiative was to make sure the COVID ward was prioritized, above other wards, with human resources to cater for patients. Proper staffing was done by allocating nurses every morning to make sure COVID-19 patients have staff who look after them when admitted in the ward. This was evident in the following direct comments from the participants:

“I had to allocate the staff to COVID ward, but nurses were refusing. I ensured that the COVID ward was properly staffed, though the other wards were having staff shortages.” [Mushai]

“Every morning we would assemble in the matron’s office and allocate nurses to work in the COVID ward, even if it could be for a day.” [Mushoni]

Converting chronic wards into COVID wards

The chronic wards were converted to be COVID-19 wards. Patients were spaced out, as per COVID-19 guidelines. The initiative was to curb staff shortages by nurses from the converted wards. The participants confirmed:

“We had to reorganize the hospital immediately, and group the patients, to develop a COVID ward from those suspected and confirmed. This enabled us to utilise nurses from the converted wards” [Malindi]

Similar challenges of shortage of human resources, as Mulatwa. Mulatwa said: “As the hospital was full, and overcrowded, which was increasing workoverload and staff shortage, we ended up converting our chronic TB ward into COVID-19 wards for our nurses to care for COVID-19 patients”.

Combining the wards

The expected surge of COVID-19 cases has forced hospital managers to consider calling in reinforcements from all wards. For managing the COVID-19 staff challenges, wards were merged so that the available space and staff could be used to cater for the patients. Participants had to say: “The ward was full, and I had to open another ward. I had to mix male medical and surgical wards. Staff from both wards combined so as to better manage the COVID-19 ward.” [Malindi]

“It was not easy to manage the wards because of severe staff shortages, but combining the wards helped as I could allocate both staff in the COVID-19 ward” [Khakhathi]

Admitting only critically ill patients

As the burden of patient influx increased, the hospital management agreed with doctors and nurse managers that only critical patients should be admitted, and the non-critical COVID-19 patients were sent to isolate at their homes. This was also done to curb staff shortages that were so severe and the minimal resources that could not cater for all the patients. The following quotes support this theme: Mulatwa had this to say: “It was difficult to plan because the ward was full. Patients who were not critical were discharged. Only the critically ill patients were admitted”

“We had to come to the drawing board with our doctors and the hospital assistant manager, to reach a consensus of only admitting the critically ill. It was too heavy to work with very few numbers of nurses.” [Maemu]

Theme 4 Flexible staff allocation

The theme unfolded with three subthemes, namely, reshuffling of staff, centralized daily allocation, and nurses working overtime.

Reshuffling of staff

To cover the created COVID ward with staff, staff reshuffling was done from other wards. The hospital was left to operate with very few nurses. Nurse managers had to agree with the hospital assistant managers on reshuffling nurses from other wards to feed the COVID ward. The following are the participant’s quotes in support of the theme: “The problem was when the staff members were infected, from theatre, surgical and pediatrics wards, we had severe shortages. So we had to do daily allocation to reshuffle and circulate nurses from other wards to patch the shortage. Though some were reluctant, I had to plead them.” [Malindi] ‘’It was not easy,[pause], despite converting, combining the wards and admitting only critically ill patients, we agreed with hospital assistant managers on reshuffling staff at any time of the day depending on the situation at hand in our COVID ward’ [Muhangwi]

Centralized daily allocation

Daily allocation was then centralized to come from the hospital assistant manager [matron], who allocates staff to different wards of the hospital. The following are quotes to support the theme: “It was hard as nobody wanted to be allocated to the COVID ward. The staff allocation was then left to be co-ordinated from the matron’s office. People from other wards would come to assist, and they had to come with the allocation letter to assist.” [Malindi]

“When allocation was centralised, I could not even borrow nurses from the other wards. I would only report the shortage to the matron, who then would send nurses to report in the COVID ward after I pleaded for assistance” [Mulatwa].

Working overtime

Nurse Managers reported that for ward coverage, they were pleading for overtime approval to curb the staff shortages. Nurse managers suggested that nurses be allowed to perform overtime, but had a constraint that there would not be any payment for such work and, yet, this would partially solve staff shortages. The nurse managers verbalized that: “As a nurse manager, I feel there should be enough staff. The overtime payment for staff replacing the sick members should be approved.” [Khakhathi]

“Support received from the hosipital manager was ineffective. When I requested a nurse, I was informed that there was no overtime to be paid. Nurses were reluctant to work for overtime saying they are not paid.” [Mulatwa]

“Those who were called to work overtime demanded overtime payment which needed prior approval, so the office would be closed and that meant nurses would not come to assist. That meant all nurses on duty, including me as a nurse manager, should work 07:00–19:00.” [Malindi]

Discussion

Nurse managers’ experiences regarding absenteeism of nurses and other staff members

Nurse managers reported that the absenteeism rate for nurses as well as other staff members has increased drastically as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in the hospital. From this study’s findings, nurses were absent as a result of being infected with COVID-19 whether it be from the wards or the community. When infected they were to be in quarantine or be admitted so as for them to also recover from the pandemic. Quarantine after a COVID-19 positive test was to be for 10 or more days and such period was also putting pressure on the poorly resourced wards. The ill-health for nurses and staff members thus contributed to absenteeism and making the nurse managers’ work of allocating adequate staff to care for COVID-19 patients difficult. A study conducted by Groenewold et al. [24] concurs with the findings of this study regarding increased absenteeism of workers, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on full-time workers in April 2020. They indicated that absenteeism was significantly higher than expected among several occupational groups in the US. However, the reason for the absenteeism was not mentioned. They did not indicate whether it was because staff members were sick or whether they had other problems. The absenteeism of nurses specifically affects patient care and, thus, increases the burden on the few nurses who report for duty. Other than staff members being ill, they absented themselves from work to care for their loved ones.

Taking care of loved ones infected with COVID-19 at home

Nurse manager’s also alluded to the fact that other staff members would be absent even though they were healthy because family members might have been infected with COVID-19 and they were home caring for those family members. Such incidences also scared nurse managers, especially when these staff members wanted to return for duty. Nurse manager’s could not be sure whether they were healthy when such staff members wanted to come back to work, and they might be putting patients and other staff members at risk of contracting the COVID-19 virus. Staff members who reported that they were COVID-19 contacts were further increasing the burden of patient care related to absenteeism. The absence of other nurses in the ward contributed to staff shortage while causing those nurses who remained in the ward to be overworked. According to a study by Nasrin, Tahereh, Aziz, and Heshmatolah [25], the large volume of services required during the COVID-19 pandemic exhausted nurses. This is aggravated by the condition in which some COVID-19 patients find themselves, as some patients are completely helpless and cannot do anything for them; nurses were, therefore, meeting most of their health care needs. And thus, the multiplicity of patients’ health care needs and a limited number of nursing staff increases the nurses’ workload, hence, physical fatigue.

Fear influenced testing for COVID-19

Nurse manager’s revealed that nurses were constantly testing for COVID-19, to the extent where they would leave their wards to go to private health institutions to test for COVID-19, using medical aid. Some of them were faking symptoms of COVID-19. Some nurses were reported to be faking the COVID-19 illness as a result of fear of having contracted the disease. The nurses who had fear experienced false COVID-19 symptoms and had to be tested for COVID-19. Whilst they await the results which used to take three to four days, they would be in quarantine which further left the ward with the shortage.

The study findings were supported by Labrague and De los Santos [26], noting that the nature of work done by frontline nurses, being directly involved in patient care, places them at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 than the general population. This could contribute to their feelings of apprehension or fear of being infected or unknowingly infecting others, including their family members and friends, hence, the need to always want to test for the COVID-19 virus. That is also coupled with concerns of the increased number of patients, increased workload and provision of COVID-19 patient care taking place during the pandemic, which intensifies fears among nurses, affecting their psychological and emotional well-being, and work performance [26].

Staff attrition

The involuntary attrition rate was reported to have increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses above 55 years reported being leaving the wards for early retirement which they felt was influenced by fear from the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, other nurses were reported that they chose to resign to be safe from the COVID-19 pandemic. Reporting the death of staff members increased the rate of attrition increases than what was envisaged normally without the COVID-19 pandemic. The high mortality rate among nurses due to COVID-19 infection was identified as one of the factors leading to even greater shortages and increased burdens of providing patient care. Most of the nurse managers experienced the death of staff members in their wards. Those staff members who were either taking early retirement, resigning, or dying as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak were never replaced putting more pressure on staff shortages on the nurse managers.

Bagnasco, Zanini, Hayter, Catania, and Sassco [27] in a study conducted in Italy, confirmed that frontline COVID-19 caregiving is exhausting, especially over long hours. At some point, replacement staff will be needed to enable others to take some rest and restore their energy. This partially supports the study’s findings, though, in the situation in Limpopo, nurses retired or resigned, which led to increased shortages of staff and, thus, overwhelming patient care being left to staff during the pandemic.

Kursumovic, Lennane, and Cook’s [28] study showed that health care workers are at risk of contracting Coronavirus through occupational exposure. The findings from the study presented health care workers’ mortality, which sadly continues to grow, with nearly 200 deaths highlighted, of which 157 were confirmed as of the 3rd May 2020. This number represents 48 nurses, 35 support workers, 26 other health care professionals, 25 doctors, and 23 nonclinical staff; 96% of doctors, 75% of nurses, and 59% overall. With such a high mortality rate among health care workers, staff shortages continue to skyrocket, which goes on to cripple patient care in the wards. As most nurses and some staff members continued to be absent from the work stations from the COVID-19 consequences, nurse managers created COVID-19 centered management.

COVID-19 centered management

Nurse manager’s further devised ways to curb staff shortages. They attempted to curb the staff shortages in COVID-19 wards by working with hospital management and doctors so that an agreement was reached to combine different wards to create a COVID-19 ward. The male and female wards were combined to create space for patients diagnosed with COVID-19, who was then considered a priority. The chronic wards were converted into a COVID-19 ward with two meters of social distance between patients’ beds. Participants indicated that space creation was very important and having wards combined created the necessary space. COVID-19 was prioritized and some of the cubicles of the converted ward were used to store COVID-19 personal protective equipment [PPE]. After the wards were converted and combined, each nurse manager was approached so that the staff members could be reshuffled and allocated in the COVID-19 wards, since the wards were new and lacked staff. The resource shortages also prompted the hospital to reduce the number of those who were being admitted. Participants verbalized that they were only admitting critical patients who could be requiring oxygen. This is consistent with the study by Wu, et al. [29] who also indicated that they had designated COVID-19 wards for catering to COVID-19 patients only, which helped prevent infections among hospital patients.

Similar interventions of creating new wards for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were done in Singapore to make sure there was adequate manpower to provide nursing care and for staff safety. General ward nurses were also deployed to support COVID-19 isolation wards [30]. After combining and converting wards, nurse managers also considered flexible staff allocation.

Flexible staff allocation

Nurse manager’s indicated that they applied different methods to allow flexible staff allocation. Nurses reshuffled from their usual wards to also circulate to the COVID-19 ward. The hospital matron was also involved in allocating staff from other wards to man the COVID-19 ward fully. Nurse manager’s sought approval of overtime as they were of the idea that overtime pay could attract some nurses to work after hours, to cover for staff shortages. The study finding differs from the WHO guidelines on health service management. In the guidelines, hospitals are encouraged to recruit retired professionals, employ unemployed nurses, and use enrolled nurses and assistant nurses for promote and preventive health, such as immunization [1]. The study finds, thus, differs from the study by Wu, et al. [29] who assert that during COVID-19, nurses allocated to such wards were to work for only four hours per day to minimize the risk of infection and use of nurses on reserve were utilized. The reserve nurses comprised of those who had volunteered from other wards and were trained on emergency care on COVID-19. Unlike the findings of this study, there was no staff shortage in the study conducted in China in the COVID-19 designated wards, irrespective of the COVID-19 pandemic [29]. Similarly, a study conducted in Iran reported that nurse managers moved nurses between wards, called for volunteers from other wards, and created a flexible work schedule to feed COVID-19 wards with staff when faced with staff shortages. Furthermore, managers also had to recruit contract and temporary staff for feeding the COVID-19 ward [6].

Conclusion

The study highlighted human resource challenges experienced by nurse managers in a rural hospital in the Vhembe district. Different reasons causing absenteeism such as ill-health, family responsibility, fear of COVID infections, quarantine following the COVID-19 test, and high attrition rates of nurses and staff, were presented. Nurse manager’s further verbalized ways to try and solve staff challenges attributed to the COVID-19 outbreak. Staff shortages seemed common and challenging among nurse managers throughout the district, which requires immediate support and interventions. Such support if rendered immediately, when the study findings are shared with the district managers can help to solve the staff demand challenges worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

The study cannot be generalized to other settings as it was conducted in the Vhembe district hospital only. The study used descriptive phenomenology and, as such, a limited number of participants were interviewed as per the nature of the study. Data was not collected through face-to-face interviews due to the COVID-19 restriction rules and some of the physical reactions expressed by participants might, therefore, have been missed.

Data Availability

The dataset and analyzed reports for this study are available on reasonable request from both the author and co-authors.

Consent

After the recruitment of participants, consent forms were sent to their e-mail addresses for completion and to be returned to the researcher before the interviews took place. Participants were assured that the transcriptions and recordings of all conversations were to be kept confidential, and the participants were interviewed in a closed room to ensure confidentiality and privacy during data collection calls.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Vhembe district manager Health and the Chief Executive Officer for permitting the study to take place. Also, our gratitude to the participants for voluntarily consenting to participate in the study.

REFERENCES

- https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/2019-novel-coronavirus-overview-of-the-state-of-the-art-and-outline-of-key-knowledge-gaps-slides.

- Baker MG, Peckham TK, Seixas NS. Estimating the burden of United States workers exposed to infection or disease: A key factor in containing the risk of COVID-19 infection. PloS One. 2020,15:e0232452.

- Cao Y, Li Q, Chen J, et al. 2020. Hospital emergency management plan during the COVID-19 epidemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020,27:309-311.

- https://onlinenursing.duq.edu/blog/nurses-responding-to-global-pandemics/.

- https://soso.bz/Ac8J2KTV.

- Poortaghi S, Shahmari M, Ghobadi A. Exploring nursing managers’ perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: A content analysis study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:1–10.

- Felice C, Di Tanna GL, Zanus G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers in Italy: Results from a national e-survey. J Comm Heal. 2020;45:675–683.

- Kramer V, Papazova I, Thoma A, et al. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:271-281.

- White JH. A phenomenological study of nurse managers and assistant nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Nurs Manag. 2021:00:1-10.

- Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6):e790–e798.

- Corless IB, Milstead JA, Kirksey KM. American academy of nursing on policy, practice guidelines: Expanding nursing’s roles in responding to global pandemics, 2018. Ame Acad Nurs Policy. 2018;66:412–415.

- https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/workforce/7-ways-hospitals-states-can-cope-with-nursing-shortage-during-coronavirus-patient.

- Babbie E. The practice of social research. 15th edition. United States of America: Cengage Learning Inc., 2020.

- Bless C, Higson-Smith C, Sithole SL. Fundamental of social research methods: an African perspective. 5th edition. Cape Town: Juta and Company Limited, 2018.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research. 9th edition. China: Wolters Kluwer (2018).

- Booyens S, Bezuidenhout M. Dimensions of healthcare management. Cape Town: Juta and Company. 2018.

- Gray JR, Grove SK, Sutherland S. Practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence. 8th edition. China: Elsevier, 2017.

- Ellis P. Evidence-based research in nursing. 3rd edition. London: Sage Publishers, 2016.

- Malmqvist J, Hellberg K, Mollas G, et al. Conducting the pilot study: A neglected Part of the Research Process? Methodological findings supporting the Importance of Piloting in Qualitative Research studies. Int J Qualitative Meth. 2019;18:1-11

- Kvale S and Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3rd edition. CA. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2015.

- Preethi S. Remote consent clinical research. Clin Trial Pract Open J. 2019;1(1),

- De Vos AS, Strydom H, Fouche CB, et al. Research at grassroots. Pretoria: Van Schaik, 2011.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage Publications, 1985.

- Groenewold MR, Burrer SL, Ahmed F, et al. Health-related workplace absenteeism among full-time workers-United States, 2017–18 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:577–582.

- Nasrin G, Tahereh T, Aziz K, et al. Exploring nurses’ perception about the care needs of patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing. 2020;19:119.

- Labrague LJ, De los Santos JAA. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organizational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1653-1661.

- Bagnasco A, Zanini M, Hayler M, et al. COVID-19 – A message from Italy to global nursing. J Adv Nurs 2020;76:2212-2214.

- Kursumovic E, Lennane S, Cook TM. Deaths in health care workers due to COVID-19: The need for robust data and analysis. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:989-992

- Wu X, Zheng S, Huang J, et al. Contingency nursing management in designated hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86:1-5.

- Goh AMJ, Chia J, Zainuddin Z, et al. Challenges faced by direct care nurse managers during the initial Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A reflection. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 2021;30:85-87.