Impact of atrial fibrillation on long-term survival after cardiac valve surgery with or without coronary artery bypass

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Nasir Shariff

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA

Tel: 412-647-5429

Fax 412-647-1654

E-mail: nasirshariff@gmail.com

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact support@pulsus.com

[ft_below_content] =>Keywords

Cardiac valve surgery; Long-term mortality; Preoperative atrial fibrillation; Postsurgical atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery. AF in these patients can be present in the preoperative period or may occur in the postoperative period. Patients with preoperative AF (PPAF) undergoing valve surgery have a higher long-term mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm [1,2]. Postsurgical AF (PSAF) has also been associated with longer hospital stay and worse outcomes in cardiac surgery patients [3-5]. In addition, it is well established that in nonsurgical patients, new-onset AF is associated with higher mortality during the initial months of diagnosis compared with patients in sinus rhythm and those with chronic AF [6-8]. The objective of the present study was to determine whether PSAF in patients undergoing valve surgery carried the same, lesser or greater impact on mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm or PPAF. To our knowledge, no studies have compared the effects of PPAF and PSAF on outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of the electronic health records of consecutive patients who underwent cardiac valve surgery at the authors’ institution during the years 2005 to 2007 was conducted. Lehigh Valley Health Network (Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA) maintains a database of all cardiac surgical patients. All elective, urgent or emergency surgical procedures were included in the study. Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in addition to the valve surgery were included. Baseline characteristics, medical history, medicine use and hospital course were extracted from an electronic medical record database. A secondary individual chart review for all included charts was performed by the first author. Long-term mortality outcome was obtained from the Social Security Death Index. The last date of query was July 31, 2011. Patients <18 years of age, as well as those undergoing isolated CABG, were excluded from the study. The institutional review board at Lehigh Valley Health Network granted ethics approval for the present study.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were confirmed or obtained from the history and physical examination at the index admission, and the daily progress notes and discharge summaries were studied for further information. Preoperative medication use was defined as patients taking the medication within 48 h before the surgical procedure. The use of these medications after the surgery or at discharge was not assessed. Information on left atrial diameter and left ventricular wall thickness were obtained from transthoracic echocardiogram obtained within six months before the surgery. When transthoracic echocardiographic information was not available, preoperative transesophageal echocardiographic data were used. Lehigh Valley Health Network does not specifically mandate a preoperative protocol for prevention of AF; the use of amiodarone was left to the discretion of the individual surgeon.

PPAF was defined as patients in AF before undergoing cardiac surgery. This was irrespective of whether the patient underwent AF ablation or the Maze procedure during the valve surgery. Patients with a history of AF but who were in sinus rhythm were not included in this group. PSAF was defined as patients in sinus rhythm before surgery who had an entry into the record or noted AF on the postoperative electrocardiogram or telemonitor recording during hospitalization. Patients with a history of paroxysmal AF who were in sinus rhythm at the time of undergoing the surgery could be included in either the sinus rhythm group or the PSAF group, depending on the occurrence of AF after surgery. No distinction was made regarding whether the arrhythmia was associated with hemodynamic compromise or with symptoms. AF status was assigned irrespective of the duration of the arrhythmia and the use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Data regarding postoperative complications, including stroke, renal failure and gastro-intestinal events, were collected using standardized definitions consistent with the STS National Database [9].

Patients were divided into three cohorts: cohort A, patients in sinus rhythm before and after surgery; cohort B (PPAF), patients in AF before undergoing the surgery; and cohort C (PSAF), patients in sinus rhythm before the surgery and with AF after the surgery.

Group comparisons were performed using the χ2 test, t test, ANOVAs and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests where appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. For measures showing significant differences, appropriate ORs and 95% CIs were calculated to enable ease of interpretation. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier’s method to compare the three groups on mortality outcomes. The Kaplan-Meier curves were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression analysis for mortality outcome was adjusted for the following baseline variables: age; sex; diabetes; hypertension; smoking; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; type of valve surgery; left ventricular ejection fraction; use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers and amiodarone; CABG; Maze/ pulmonary isolation surgery; and postoperative complications (cerebrovascular events, renal failure and gastrointestinal events). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 15.0 (IBM Corporation, USA); P≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 556 patients who underwent cardiac valve surgery during the study period, 42% were women. The mean (± SD) age of the study population was 70.2±11.6 years. Of these patients, 27.5% had a history of diabetes, 79.1% had a history of hypertension and 7.7% had a history of stroke. In addition to the valve surgery, 44.4% underwent CABG. Mitral valve surgery was performed in 29.7% of patients; 74.1% underwent aortic valve surgery. Medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and beta-blockers, were taken by 32.7%, 17.3% and 48.2% of patients at the time of surgery, respectively. Amiodarone was being used by 3.4% of patients and statins by 53.8%. Of the patients included, 11.7% of patients were current smokers and 55.9% had a history of tobacco use. The mean left atrial diameter was 4.72±1.14 cm and mean left ventricular wall thickness was 1.36±0.50 cm. The average time on bypass was 139.2±48.8 min. Of the study population, 139 (25% of the total patients) had underlying PPAF before surgery and 124 (30% of at-risk patients) developed PSAF. The average follow- up period was 50.8±19.8 months.

Comparison of baseline characteristics among the three cohorts

Patients who remained in sinus rhythm were significantly younger than patients who developed PSAF (67.8±12.5 years versus 72.4±9.9 years; P<0.01) and patients in PPAF (73.1±9.9 years; P<0.01) before the surgery. The three groups were similar with regard to sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, and duration of bypass and CABG performed (Table 1). Patients in PPAF had significantly dilated left atria compared with patients in sinus rhythm before surgery. The left ventricular wall thickness was similar in the three cohorts.

| Characteristic | Sinus rhythm | Preoperative AF | Postsurgical AF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=293) | (n=139) | (n=124) | ||

| Age, years | 67.8±12.5 | 73.1±9.9* | 72.4±9.9* | |

| Female sex | 124 (42.9) | 56 (40.3) | 53 (42.7) | |

| Smoker (active) | 43 (14.9) | 11 (7.9) | 11 (8.8) | |

| History of heart failure | 102 (35.3) | 83 (59.7)* | 37 (29.8) | |

| LVEF, % | 53.2±12.0 | 52.9±11.9 | 54.2±12.1 | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 222 (76.8) | 117 (84.2) | 98 (79.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 77 | (26.6) | 41 (29.5) | 34 (27.4) |

| History of tobacco use | 158 (54.7) | 79 (56.8) | 73 (58.9) | |

| COPD | 68 (23.5) | 51 (36.7)* | 29 (23.4) | |

| Cerebrovascular | 22 (7.6) | 13 (9.4) | 8 (6.5) | |

| accident | ||||

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| Left ventricular | 1.35±0.31 | 1.34±0.31 | 1.38±0.32 | |

| thickness, cm | ||||

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 4.53±1.0 | 5.2±1.4* | 4.6±0.8 | |

| Surgical details | ||||

| Cardiopulmonary | 138.0±50.9 | 145.6±43.6 | 132.8±50.7 | |

| bypass duration, min | ||||

| Coronary bypass | 128 (45.4) | 51 (36.7) | 66 (53.2) | |

| surgery | ||||

| Maze/pulmonary vein | 1 (0.3) | 64 (46.4)* | 0 (0.0) | |

| isolation | ||||

| Mitral valve surgery | 75 (26.0) | 62 (44.6)* | 28 (22.6) | |

| Aortic valve surgery | 225 (77.9) | 84 (60.4)* | 99 (79.8) | |

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. *P≤0.05 compared with patients with sinus rhythm. AF Atrial fibrillation; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery (n=556)

Hospital stay and mortality outcomes

Patients who developed PSAF had a significantly higher incidence of prolonged ventilation after the surgery compared with patients in sinus rhythm and patients with PPAF (Table 2). There were also more stroke events in patients with PSAF compared with patients with sinus rhythm and PPAF. Patients with PSAF had a longer hospital stay compared with patients with sinus rhythm (11.3±8.3 days versus 7.12±4.9 days; P<0.01). Patients with PPAF had a similar duration of hospital stay as PSAF (10.5±6.1 days versus 11.3±8.3 days).

| Outcome | Sinus rhythm | Preoperative AF | Postsurgical AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=293) | (n=139) | (n=124) | |

| Prolonged ventilation | 13 (4.5) | 8 (5.8) | 14 (11.3)* |

| Heart block | 19 (6.6) | 10 (7.2) | 7 (5.6) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.4) |

| Perioperative MI | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Stroke | 10 (2.4) | 5 (3.6) | 10 (8.0)* |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal events | 3 (1.0) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (0.8) |

| Renal failure | 14 (4.8) | 7 (5.1) | 12 (9.6) |

| Dialysis | 8 (2.7) | 3 (2.2) | 5 (4.0) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.4) |

| Septicemia | 7 (2.4) | 2(1.4) | 7 (5.6) |

| Hospital stay duration, | 7.12±4.9 | 10.5±6.1* | 11.3±8.3* |

| days, mean ± SD | |||

| 30-day mortality | 15 (5.1) | 8 (5.7) | 6 (4.8) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. *P≤0.05 compared with patients with sinus rhythm. AF Atrial fibrillation; MI Myocardial infarction

Table 2: Comparison of outcomes of the three cohorts (n=556)

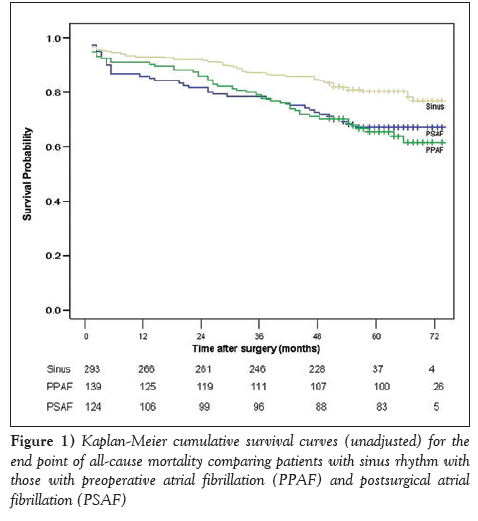

Overall, five-year survival following surgery was 73.4%. Patients who were in sinus rhythm had a better survival outcome, with a fiveyear rate of 78.4%. Patients who had AF before surgery and those who developed PSAF had a significantly lower survival rate (63.8% and 67.2%, respectively; log-rank P=0.002). Comparisons of long-term survival for the three groups are presented in Figure 1.

Patients with PPAF and PSAF fared worse postoperatively than patients in sinus rhythm. There was no statistically significant difference in long-term survival between patients with PPAF and PSAF (logrank P=0.748). On the other hand, there was a statistically significant difference in unadjusted survival when comparing patients with sinus rhythm with patients with PSAF and PPAF (log-rank P=0.001 and P=0.007, respectively). After adjusting for age, PPAF and PSAF remained associated with worse mortality outcomes. The age-adjusted mortality was 1.043 (95% CI 1.004 to 1.083; P<0.05) for patients with PPAF and 1.046 (95% CI 1.004 to 1.090; P<0.05) for patients with PSAF compared with patients in sinus rhythm. The age-adjusted mortality for PSAF compared with PPAF was 1.003 (95% CI 0.959 to 1.048; P=0.898). On subgroup analysis of patients with and without concurrent CABG procedure, the outcome in patients with PSAF and PPAF was significantly worse than patients remaining in sinus rhythm (Figure 2). On analysis of patients undergoing aortic valve surgery, patients with PPAF and PSAF had lower survival compared with sinus rhythm. Among patients undergoing mitral valve surgery, PSAF was associated with poor outcomes (log-rank P=0.04) while PPAF was associated with similar mortality outcomes as sinus rhythm (log-rank P=0.62) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality in patients undergoing valve surgery. A With coronary bypass surgery; B Without concomitant coronary bypass surgery; C Mitral valve surgery; D Aortic valve surgery. PPAF Preoperative atrial fibrillation; PSAF Postsurgical atrial fibrillation

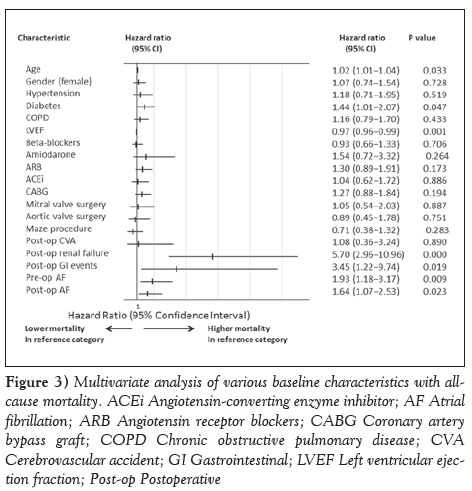

On multivariate Cox regression analysis, age was associated with higher mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.02 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.04]; P=0.033) while sex, hypertension, type of valve surgery, preoperative medication use, postoperative cerebrovascular events, CABG and pulmonary vein isolation surgery were not associated with long-term mortality (Figure 3). Diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, postoperative renal failure and gastrointestinal events were also associated with increased mortality. The adjusted risk for all-cause mortality was 1.93 (95% CI 1.18 to 3.17; P=0.01) for patients with PPAF and 1.64 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.53; P=0.02) for PSAF (Figure 3). Despite the significant difference between the groups, the history of heart failure did not affect the association of PPAF (HR 1.587 [95% CI 1.072 to 2.348]; P=0.02) and PSAF (HR 1.366 [95% CI 1.113 to 1.677]; P<0.01) on long-term mortality.

Figure 3: Multivariate analysis of various baseline characteristics with allcause mortality. ACEi Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF Atrial fibrillation; ARB Angiotensin receptor blockers; CABG Coronary artery bypass graft; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA Cerebrovascular accident; GI Gastrointestinal; LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction; Post-op Postoperative

Discussion

The present study is the first to compare duration of hospital stay and long-term mortality outcomes between patients with PPAF and PSAF following valve surgery. The present study identified the association of PPAF and PSAF with increased long-term mortality in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery compared with sinus rhythm irrespective of whether the patient underwent concomitant CABG surgery. We also established that patients with PSAF and PPAF had a longer hospital stay than patients in sinus rhythm. Our study underscores the importance of perioperative care in these high-risk patients and the need for close follow-up after discharge. Our finding of age, diabetes mellitus, postoperative gastrointestinal complications and renal failure as factors with higher mortality after valve surgery are consistent with previous findings [10-12].

The association of PPAF and PSAF with long-term mortality after cardiac surgery has been reported in several studies. AF before CABG surgery has been recognized as an independent predictor of prolonged hospital stay and was associated with a 40% increase (P=0.02) in allcause mortality over seven years in patients undergoing CABG [13]. A history of AF before aortic valve replacement surgery for low-gradient stenosis has also been associated with an increased five-year mortality [1]. In a multicentre study involving 522 patients with end-stage renal disease who were undergoing cardiac surgery, preexisting AF was associated with late mortality but not perioperative mortality [2]. Of the patients in this multicentre study, 17.2% had undergone valve surgery and 19.9% had valve with CABG surgery.

Unlike preoperative AF, there have been reports of variable association of PSAF with long-term mortality outcomes in patients undergoing valve surgery. In a study by Mariscalco et al [14] during the eight-year follow-up of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, PSAF was independently associated with long-term survival in CABG patients but not in patients undergoing isolated valvular surgery. Because the study did not define the specifications of the valve, and considering that the study population was much younger than our study group (66.2 years versus 70.2 years), there may have been differences in the type of valve being surgically replaced/repaired, in addition to the contribution of age on the occurrence of PSAF and outcomes. Similar to our findings, it was also noted in a study by Bramer et al [3] that PSAF after mitral valve surgery predicted late mortality. There was noted higher mortality in patients with PSAF, even from the early phase after the surgery. In another study by Filardo et al [4], 1039 patients undergoing aortic valve replacement were assessed.The 10-year unadjusted survival was 50.8% for patients with PSAF and 59.4% for patients without PSAF. Similar to our study, patients with PSAF were significantly older compared with patients in sinus rhythm (74.2 years versus 65.7 years). Approximately one-half of the patients had concomitant CABG surgery. The unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves depicted increased mortality, even from the early phase after the surgery. In a study by Attaran et al [15], patients developing PSAF after undergoing aortic valve surgery had higher longterm mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm population. Patients undergoing mitral valve surgery did not have a similar association of PSAF with mortality.

Although these studies have shown a significant effect of AF on long-term mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, our study is the first to comprehensively and simultaneously compare PPAF and PSAF with respect to sinus rhythm on long-term outcomes in patients undergoing valvular surgery. Our finding of higher mortality in patients with PSAF compared with PPAF after mitral valve surgery is intriguing. There was also a trend toward higher mortality in the initial period of surgery in patients with PSAF compared with PPAF. PSAF following cardiac surgery has been identified to occur in predisposed patients (older, larger left atrial size and thicker left ventricular walls) [16-20] with a trigger factor that could be inflammation, infection or heightened sympathetic activity [21-25]. Thus, PSAF may be a marker of higher mortality in the earlier phase of the surgery rather than a direct cause. Other reasonable explanations for this finding may be that the potential for developing adverse effects to antiarrhythmic medications and anticoagulants is highest during the initial phase, especially in this elderly population. This could also be due to the adequacy of rate control achieved over time in patients with AF, which is better than in patients with new-onset AF. Of note, new-onset AF has been shown to be associated with higher mortality than no AF or chronic AF, even in nonsurgical patients in the initial months of diagnosis [6-8]. Considering that more than one-half of patients with PSAF have recurrent AF [16] and several of these patients may develop chronic AF, this arrhythmia could contribute to higher long-term mortality comparable with patients with PPAF. Our findings are important, particularly for our aging population with higher prevalence of valvular heart disease and the risk associated with this cardiac arrhythmia.

Our findings with respect to longer duration of hospital stay in patients with pre- and post-cardiac surgery AF is consistent with previous reports [26-29]. In addition to individually comparing the two AF groups with patients in sinus rhythm, we compared the duration of hospital stay between the PSAF and PPAF cohorts. We noted that both patients with PSAF and PPAF had similar durations of hospital stay, although there was a trend toward longer stays in patients with PSAF. The longer stays could be related to the initiation of newer medication or could be a marker to suggest higher inflammation and complications in patients with PSAF.

Our study had certain limitations. The study was retrospective and conducted at a single centre, thus limiting generalizability. However, it should be noted that the baseline characteristics of our study are similar to other reported large registries of patients undergoing valve surgery [10]. We were also limited with respect to the elucidation of the cause of mortality. We did not consider the history of paroxysmal AF in the study, which could have contributed more information on the relationship of this condition to the occurrence of PSAF and outcomes. Irrespective of the presence or absence of a history of paroxysmal AF, the occurrence of PSAF prolonged hospital stay in our study. Information regarding the distinct form of AF (paroxysmal, persistent and permanent) would have provided results of these particular forms on outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery. Because our study was addressing the presence of AF in the immediate preoperative and in the postsurgical hospital stay period, this information was not collected. In addition, the acuity of surgery (urgent versus elective) would have influenced the outcomes. Although this may explain the early outcomes, this particular information would likely not have a significant effect on the long-term outcomes. Lack of data on medication use in the postoperative period, including anticoagulation use and particulars of the type of valve surgery, limits our ability to draw direct causal conclusions about role of AF. However, our well-characterized, large database of patients undergoing valve surgery with long and complete follow-up provides an opportunity to draw robust conclusions. It should be noted that the identification of AF with increased mortality does not establish a causative relationship. The unambiguous association with worse outcomes is clear from our study.

Summary

For patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery, PPAF and PSAF are associated with longer hospital stay and higher long-term mortality. Prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the relationships among these common arrhythmias and outcomes in patients undergoing valve surgeries.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Levy F,LaLuerveynFt M, Monin JL, et al. Aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis operative risk stratification and long-term outcome: A European multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1466-72.

- Schonburg M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Weinbrenner F, et al. Preexisting atrial fibrillation as predictor for late-time mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing cardiac surgery – a multicenter study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:128-32.

- Bramer S, van Straten AH, Soliman Hamad MA, et al. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation predicts late mortality after mitral valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:2091-6.

- Filardo G, Hamilton C, Hamman B, Hebeler RF Jr, Adams J, Grayburn P. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation and long-term survival after aortic valve replacement surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:474-9.

- El-Chami MF, Kilgo P, Thourani V, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1370-6.

- Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920-5.

- Ahmed A, Perry GJ. Incident atrial fibrillation and mortality in older adults with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:1118-21.

- Khan MN, Jais P, Cummings J, et al. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1778-85.

- STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database data collection forms and specifications. <www.sts.org/sts-national-database/database- managers/adult-cardiac-surgery-database/data-collection> (Accessed April 1, 2010).

- Edwards FH, Peterson ED, Coombs LP, et al. Prediction of operative mortality after valve replacement surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:885-92.

- Filsoufi F, Rahmanian PB, Castillo JG, Scurlock C, Legnani PE, Adams DH. Predictors and outcome of gastrointestinal complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2007;246:323-9.

- Rahmanian PB, Filsoufi F, Castillo JG, et al. Predicting postoperative renal failure requiring dialysis, and an analysis of long-term outcome in patients undergoing valve surgery. J Heart Valve Dis 2008;17:657-65.

- Ngaage DL, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, et al. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation influence early and late outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:182-9.

- Mariscalco G, Engstrom KG. Postoperative atrial fibrillation is associated with late mortality after coronary surgery, but not after valvular surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1871-6.

- Attaran S, Shaw M, Bond L, Pullan MD, Fabri BM. Atrial fibrillation postcardiac surgery: A common but a morbid complication. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:772-7.

- Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2004;291:1720-9.

- Shariff N, Zelenkofske S, Eid S, Weiss MJ, Mohammed MQ. Demographic determinants and effect of pre-operative angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the occurrence of atrial fibrillation after CABG surgery. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2010;10:7.

- Nakai T, Lee RJ, Schiller NB, et al. The relative importance of left atrial function versus dimension in predicting atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Am Heart J 2002;143:181-6.

- Osranek M, Fatema K, Qaddoura F, et al. Left atrial volume predicts the risk of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:779-86.

- Vogt PR, Brunner-LaRocca HP, Rist M, et al. Preoperative predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation late after successful mitral valve reconstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998;13:619-24.

- Anselmi A, Possati G, Gaudino M. Postoperative inflammatory reaction and atrial fibrillation: Simple correlation or causation? Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:326-33.

- Canbaz S, Erbas H, Huseyin S, Duran E. The role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation following open heart surgery. J Int Med Res 2008;36:1070-6.

- Elahi M, Hadjinikolaou L, Galinanes M. Incidence and clinical consequences of atrial fibrillation within 1 year of first-time isolated coronary bypass surgery. Circulation 2003;108(Suppl 1):II207-212.

- Abdelhadi RH, Gurm HS, Van Wagoner DR, Chung MK. Relation of an exaggerated rise in white blood cells after coronary bypass or cardiac valve surgery to development of atrial fibrillation postoperatively. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1176-8.

- Kalman JM, Munawar M, Howes LG, et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:1709-15.

- Auer J, Weber T, Berent R, Ng CK, Lamm G, Eber B. Postoperative atrial fibrillation independently predicts prolongation of hospital stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2005;46:583-8.

- Rubin DA, Nieminski KE, Reed GE, Herman MV. Predictors, prevention, and long-term prognosis of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Sep 1987;94:331-5.

- Banach M, Goch A, Misztal M, et al. Relation between postoperative mortality and atrial fibrillation before surgical revascularization – 3-year follow-up. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:20-3.

- Ad N, Barnett SD, Haan CK, O’Brien SM, Milford-Beland S, Speir AM. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation increase the risk for mortality and morbidity after coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:901-6.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Nasir Shariff

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA

Tel: 412-647-5429

Fax 412-647-1654

E-mail: nasirshariff@gmail.com

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact support@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery. AF in patients undergoing surgery can be categorized as preoperative AF (PPAF) or postsurgical AF (PSAF).

Objective: To determine whether PSAF in patients undergoing valve surgery had an impact on mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm or PPAF.

Methods: A total of 556 consecutive patients who underwent valve surgery were reviewed. Patients were divided into three cohorts: sinus rhythm before and after surgery (n=293); PPAF (n=139); and sinus rhythm before and AF after the surgery (PSAF) (n=124). Baseline characteristics, surgical details and outcomes were recorded.

Results: Compared with patients in sinus rhythm (mean [± SD] age 67.8±12.5 years), patients in the PPAF and PSAF groups were significantly older (73.1±9.9 years and 72.4±9.9 years, respectively). Hospital stay was significantly longer in the PPAF and PSAF groups (10.5±6.1 days and 11.3±8.3 days, respectively) compared with patients with sinus rhythm (7.12±4.9 days). During a follow-up of 51 months, all-cause mortality was significantly higher in both the PPAF and PSAF groups. This was irrespective of concomitant coronary bypass surgery. On multivariate Cox regression analysis, the adjusted risk for all-cause mortality for PPAF and PSAF was 1.93 (95% CI 1.18 to 3.17; P=0.01) and 1.64 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.53; P=0.02), respectively.

Conclusion: Patients with PSAF and PPAF have longer hospital stays and higher long-term mortality rates than patients in sinus rhythm. Long-term mortality was similar between PPAF and PSAF.

-Keywords

Cardiac valve surgery; Long-term mortality; Preoperative atrial fibrillation; Postsurgical atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery. AF in these patients can be present in the preoperative period or may occur in the postoperative period. Patients with preoperative AF (PPAF) undergoing valve surgery have a higher long-term mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm [1,2]. Postsurgical AF (PSAF) has also been associated with longer hospital stay and worse outcomes in cardiac surgery patients [3-5]. In addition, it is well established that in nonsurgical patients, new-onset AF is associated with higher mortality during the initial months of diagnosis compared with patients in sinus rhythm and those with chronic AF [6-8]. The objective of the present study was to determine whether PSAF in patients undergoing valve surgery carried the same, lesser or greater impact on mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm or PPAF. To our knowledge, no studies have compared the effects of PPAF and PSAF on outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of the electronic health records of consecutive patients who underwent cardiac valve surgery at the authors’ institution during the years 2005 to 2007 was conducted. Lehigh Valley Health Network (Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA) maintains a database of all cardiac surgical patients. All elective, urgent or emergency surgical procedures were included in the study. Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in addition to the valve surgery were included. Baseline characteristics, medical history, medicine use and hospital course were extracted from an electronic medical record database. A secondary individual chart review for all included charts was performed by the first author. Long-term mortality outcome was obtained from the Social Security Death Index. The last date of query was July 31, 2011. Patients <18 years of age, as well as those undergoing isolated CABG, were excluded from the study. The institutional review board at Lehigh Valley Health Network granted ethics approval for the present study.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were confirmed or obtained from the history and physical examination at the index admission, and the daily progress notes and discharge summaries were studied for further information. Preoperative medication use was defined as patients taking the medication within 48 h before the surgical procedure. The use of these medications after the surgery or at discharge was not assessed. Information on left atrial diameter and left ventricular wall thickness were obtained from transthoracic echocardiogram obtained within six months before the surgery. When transthoracic echocardiographic information was not available, preoperative transesophageal echocardiographic data were used. Lehigh Valley Health Network does not specifically mandate a preoperative protocol for prevention of AF; the use of amiodarone was left to the discretion of the individual surgeon.

PPAF was defined as patients in AF before undergoing cardiac surgery. This was irrespective of whether the patient underwent AF ablation or the Maze procedure during the valve surgery. Patients with a history of AF but who were in sinus rhythm were not included in this group. PSAF was defined as patients in sinus rhythm before surgery who had an entry into the record or noted AF on the postoperative electrocardiogram or telemonitor recording during hospitalization. Patients with a history of paroxysmal AF who were in sinus rhythm at the time of undergoing the surgery could be included in either the sinus rhythm group or the PSAF group, depending on the occurrence of AF after surgery. No distinction was made regarding whether the arrhythmia was associated with hemodynamic compromise or with symptoms. AF status was assigned irrespective of the duration of the arrhythmia and the use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Data regarding postoperative complications, including stroke, renal failure and gastro-intestinal events, were collected using standardized definitions consistent with the STS National Database [9].

Patients were divided into three cohorts: cohort A, patients in sinus rhythm before and after surgery; cohort B (PPAF), patients in AF before undergoing the surgery; and cohort C (PSAF), patients in sinus rhythm before the surgery and with AF after the surgery.

Group comparisons were performed using the χ2 test, t test, ANOVAs and nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests where appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. For measures showing significant differences, appropriate ORs and 95% CIs were calculated to enable ease of interpretation. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier’s method to compare the three groups on mortality outcomes. The Kaplan-Meier curves were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression analysis for mortality outcome was adjusted for the following baseline variables: age; sex; diabetes; hypertension; smoking; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; type of valve surgery; left ventricular ejection fraction; use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers and amiodarone; CABG; Maze/ pulmonary isolation surgery; and postoperative complications (cerebrovascular events, renal failure and gastrointestinal events). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 15.0 (IBM Corporation, USA); P≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 556 patients who underwent cardiac valve surgery during the study period, 42% were women. The mean (± SD) age of the study population was 70.2±11.6 years. Of these patients, 27.5% had a history of diabetes, 79.1% had a history of hypertension and 7.7% had a history of stroke. In addition to the valve surgery, 44.4% underwent CABG. Mitral valve surgery was performed in 29.7% of patients; 74.1% underwent aortic valve surgery. Medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and beta-blockers, were taken by 32.7%, 17.3% and 48.2% of patients at the time of surgery, respectively. Amiodarone was being used by 3.4% of patients and statins by 53.8%. Of the patients included, 11.7% of patients were current smokers and 55.9% had a history of tobacco use. The mean left atrial diameter was 4.72±1.14 cm and mean left ventricular wall thickness was 1.36±0.50 cm. The average time on bypass was 139.2±48.8 min. Of the study population, 139 (25% of the total patients) had underlying PPAF before surgery and 124 (30% of at-risk patients) developed PSAF. The average follow- up period was 50.8±19.8 months.

Comparison of baseline characteristics among the three cohorts

Patients who remained in sinus rhythm were significantly younger than patients who developed PSAF (67.8±12.5 years versus 72.4±9.9 years; P<0.01) and patients in PPAF (73.1±9.9 years; P<0.01) before the surgery. The three groups were similar with regard to sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, and duration of bypass and CABG performed (Table 1). Patients in PPAF had significantly dilated left atria compared with patients in sinus rhythm before surgery. The left ventricular wall thickness was similar in the three cohorts.

| Characteristic | Sinus rhythm | Preoperative AF | Postsurgical AF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=293) | (n=139) | (n=124) | ||

| Age, years | 67.8±12.5 | 73.1±9.9* | 72.4±9.9* | |

| Female sex | 124 (42.9) | 56 (40.3) | 53 (42.7) | |

| Smoker (active) | 43 (14.9) | 11 (7.9) | 11 (8.8) | |

| History of heart failure | 102 (35.3) | 83 (59.7)* | 37 (29.8) | |

| LVEF, % | 53.2±12.0 | 52.9±11.9 | 54.2±12.1 | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 222 (76.8) | 117 (84.2) | 98 (79.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 77 | (26.6) | 41 (29.5) | 34 (27.4) |

| History of tobacco use | 158 (54.7) | 79 (56.8) | 73 (58.9) | |

| COPD | 68 (23.5) | 51 (36.7)* | 29 (23.4) | |

| Cerebrovascular | 22 (7.6) | 13 (9.4) | 8 (6.5) | |

| accident | ||||

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| Left ventricular | 1.35±0.31 | 1.34±0.31 | 1.38±0.32 | |

| thickness, cm | ||||

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 4.53±1.0 | 5.2±1.4* | 4.6±0.8 | |

| Surgical details | ||||

| Cardiopulmonary | 138.0±50.9 | 145.6±43.6 | 132.8±50.7 | |

| bypass duration, min | ||||

| Coronary bypass | 128 (45.4) | 51 (36.7) | 66 (53.2) | |

| surgery | ||||

| Maze/pulmonary vein | 1 (0.3) | 64 (46.4)* | 0 (0.0) | |

| isolation | ||||

| Mitral valve surgery | 75 (26.0) | 62 (44.6)* | 28 (22.6) | |

| Aortic valve surgery | 225 (77.9) | 84 (60.4)* | 99 (79.8) | |

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. *P≤0.05 compared with patients with sinus rhythm. AF Atrial fibrillation; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery (n=556)

Hospital stay and mortality outcomes

Patients who developed PSAF had a significantly higher incidence of prolonged ventilation after the surgery compared with patients in sinus rhythm and patients with PPAF (Table 2). There were also more stroke events in patients with PSAF compared with patients with sinus rhythm and PPAF. Patients with PSAF had a longer hospital stay compared with patients with sinus rhythm (11.3±8.3 days versus 7.12±4.9 days; P<0.01). Patients with PPAF had a similar duration of hospital stay as PSAF (10.5±6.1 days versus 11.3±8.3 days).

| Outcome | Sinus rhythm | Preoperative AF | Postsurgical AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=293) | (n=139) | (n=124) | |

| Prolonged ventilation | 13 (4.5) | 8 (5.8) | 14 (11.3)* |

| Heart block | 19 (6.6) | 10 (7.2) | 7 (5.6) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.4) |

| Perioperative MI | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Stroke | 10 (2.4) | 5 (3.6) | 10 (8.0)* |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal events | 3 (1.0) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (0.8) |

| Renal failure | 14 (4.8) | 7 (5.1) | 12 (9.6) |

| Dialysis | 8 (2.7) | 3 (2.2) | 5 (4.0) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.4) |

| Septicemia | 7 (2.4) | 2(1.4) | 7 (5.6) |

| Hospital stay duration, | 7.12±4.9 | 10.5±6.1* | 11.3±8.3* |

| days, mean ± SD | |||

| 30-day mortality | 15 (5.1) | 8 (5.7) | 6 (4.8) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. *P≤0.05 compared with patients with sinus rhythm. AF Atrial fibrillation; MI Myocardial infarction

Table 2: Comparison of outcomes of the three cohorts (n=556)

Overall, five-year survival following surgery was 73.4%. Patients who were in sinus rhythm had a better survival outcome, with a fiveyear rate of 78.4%. Patients who had AF before surgery and those who developed PSAF had a significantly lower survival rate (63.8% and 67.2%, respectively; log-rank P=0.002). Comparisons of long-term survival for the three groups are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival curves (unadjusted) for the end point of all-cause mortality comparing patients with sinus rhythm with those with preoperative atrial fibrillation (PPAF) and postsurgical atrial fibrillation (PSAF)

Patients with PPAF and PSAF fared worse postoperatively than patients in sinus rhythm. There was no statistically significant difference in long-term survival between patients with PPAF and PSAF (logrank P=0.748). On the other hand, there was a statistically significant difference in unadjusted survival when comparing patients with sinus rhythm with patients with PSAF and PPAF (log-rank P=0.001 and P=0.007, respectively). After adjusting for age, PPAF and PSAF remained associated with worse mortality outcomes. The age-adjusted mortality was 1.043 (95% CI 1.004 to 1.083; P<0.05) for patients with PPAF and 1.046 (95% CI 1.004 to 1.090; P<0.05) for patients with PSAF compared with patients in sinus rhythm. The age-adjusted mortality for PSAF compared with PPAF was 1.003 (95% CI 0.959 to 1.048; P=0.898). On subgroup analysis of patients with and without concurrent CABG procedure, the outcome in patients with PSAF and PPAF was significantly worse than patients remaining in sinus rhythm (Figure 2). On analysis of patients undergoing aortic valve surgery, patients with PPAF and PSAF had lower survival compared with sinus rhythm. Among patients undergoing mitral valve surgery, PSAF was associated with poor outcomes (log-rank P=0.04) while PPAF was associated with similar mortality outcomes as sinus rhythm (log-rank P=0.62) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality in patients undergoing valve surgery. A With coronary bypass surgery; B Without concomitant coronary bypass surgery; C Mitral valve surgery; D Aortic valve surgery. PPAF Preoperative atrial fibrillation; PSAF Postsurgical atrial fibrillation

On multivariate Cox regression analysis, age was associated with higher mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.02 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.04]; P=0.033) while sex, hypertension, type of valve surgery, preoperative medication use, postoperative cerebrovascular events, CABG and pulmonary vein isolation surgery were not associated with long-term mortality (Figure 3). Diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, postoperative renal failure and gastrointestinal events were also associated with increased mortality. The adjusted risk for all-cause mortality was 1.93 (95% CI 1.18 to 3.17; P=0.01) for patients with PPAF and 1.64 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.53; P=0.02) for PSAF (Figure 3). Despite the significant difference between the groups, the history of heart failure did not affect the association of PPAF (HR 1.587 [95% CI 1.072 to 2.348]; P=0.02) and PSAF (HR 1.366 [95% CI 1.113 to 1.677]; P<0.01) on long-term mortality.

Figure 3: Multivariate analysis of various baseline characteristics with allcause mortality. ACEi Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF Atrial fibrillation; ARB Angiotensin receptor blockers; CABG Coronary artery bypass graft; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA Cerebrovascular accident; GI Gastrointestinal; LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction; Post-op Postoperative

Discussion

The present study is the first to compare duration of hospital stay and long-term mortality outcomes between patients with PPAF and PSAF following valve surgery. The present study identified the association of PPAF and PSAF with increased long-term mortality in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery compared with sinus rhythm irrespective of whether the patient underwent concomitant CABG surgery. We also established that patients with PSAF and PPAF had a longer hospital stay than patients in sinus rhythm. Our study underscores the importance of perioperative care in these high-risk patients and the need for close follow-up after discharge. Our finding of age, diabetes mellitus, postoperative gastrointestinal complications and renal failure as factors with higher mortality after valve surgery are consistent with previous findings [10-12].

The association of PPAF and PSAF with long-term mortality after cardiac surgery has been reported in several studies. AF before CABG surgery has been recognized as an independent predictor of prolonged hospital stay and was associated with a 40% increase (P=0.02) in allcause mortality over seven years in patients undergoing CABG [13]. A history of AF before aortic valve replacement surgery for low-gradient stenosis has also been associated with an increased five-year mortality [1]. In a multicentre study involving 522 patients with end-stage renal disease who were undergoing cardiac surgery, preexisting AF was associated with late mortality but not perioperative mortality [2]. Of the patients in this multicentre study, 17.2% had undergone valve surgery and 19.9% had valve with CABG surgery.

Unlike preoperative AF, there have been reports of variable association of PSAF with long-term mortality outcomes in patients undergoing valve surgery. In a study by Mariscalco et al [14] during the eight-year follow-up of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, PSAF was independently associated with long-term survival in CABG patients but not in patients undergoing isolated valvular surgery. Because the study did not define the specifications of the valve, and considering that the study population was much younger than our study group (66.2 years versus 70.2 years), there may have been differences in the type of valve being surgically replaced/repaired, in addition to the contribution of age on the occurrence of PSAF and outcomes. Similar to our findings, it was also noted in a study by Bramer et al [3] that PSAF after mitral valve surgery predicted late mortality. There was noted higher mortality in patients with PSAF, even from the early phase after the surgery. In another study by Filardo et al [4], 1039 patients undergoing aortic valve replacement were assessed.The 10-year unadjusted survival was 50.8% for patients with PSAF and 59.4% for patients without PSAF. Similar to our study, patients with PSAF were significantly older compared with patients in sinus rhythm (74.2 years versus 65.7 years). Approximately one-half of the patients had concomitant CABG surgery. The unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves depicted increased mortality, even from the early phase after the surgery. In a study by Attaran et al [15], patients developing PSAF after undergoing aortic valve surgery had higher longterm mortality compared with patients in sinus rhythm population. Patients undergoing mitral valve surgery did not have a similar association of PSAF with mortality.

Although these studies have shown a significant effect of AF on long-term mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, our study is the first to comprehensively and simultaneously compare PPAF and PSAF with respect to sinus rhythm on long-term outcomes in patients undergoing valvular surgery. Our finding of higher mortality in patients with PSAF compared with PPAF after mitral valve surgery is intriguing. There was also a trend toward higher mortality in the initial period of surgery in patients with PSAF compared with PPAF. PSAF following cardiac surgery has been identified to occur in predisposed patients (older, larger left atrial size and thicker left ventricular walls) [16-20] with a trigger factor that could be inflammation, infection or heightened sympathetic activity [21-25]. Thus, PSAF may be a marker of higher mortality in the earlier phase of the surgery rather than a direct cause. Other reasonable explanations for this finding may be that the potential for developing adverse effects to antiarrhythmic medications and anticoagulants is highest during the initial phase, especially in this elderly population. This could also be due to the adequacy of rate control achieved over time in patients with AF, which is better than in patients with new-onset AF. Of note, new-onset AF has been shown to be associated with higher mortality than no AF or chronic AF, even in nonsurgical patients in the initial months of diagnosis [6-8]. Considering that more than one-half of patients with PSAF have recurrent AF [16] and several of these patients may develop chronic AF, this arrhythmia could contribute to higher long-term mortality comparable with patients with PPAF. Our findings are important, particularly for our aging population with higher prevalence of valvular heart disease and the risk associated with this cardiac arrhythmia.

Our findings with respect to longer duration of hospital stay in patients with pre- and post-cardiac surgery AF is consistent with previous reports [26-29]. In addition to individually comparing the two AF groups with patients in sinus rhythm, we compared the duration of hospital stay between the PSAF and PPAF cohorts. We noted that both patients with PSAF and PPAF had similar durations of hospital stay, although there was a trend toward longer stays in patients with PSAF. The longer stays could be related to the initiation of newer medication or could be a marker to suggest higher inflammation and complications in patients with PSAF.

Our study had certain limitations. The study was retrospective and conducted at a single centre, thus limiting generalizability. However, it should be noted that the baseline characteristics of our study are similar to other reported large registries of patients undergoing valve surgery [10]. We were also limited with respect to the elucidation of the cause of mortality. We did not consider the history of paroxysmal AF in the study, which could have contributed more information on the relationship of this condition to the occurrence of PSAF and outcomes. Irrespective of the presence or absence of a history of paroxysmal AF, the occurrence of PSAF prolonged hospital stay in our study. Information regarding the distinct form of AF (paroxysmal, persistent and permanent) would have provided results of these particular forms on outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery. Because our study was addressing the presence of AF in the immediate preoperative and in the postsurgical hospital stay period, this information was not collected. In addition, the acuity of surgery (urgent versus elective) would have influenced the outcomes. Although this may explain the early outcomes, this particular information would likely not have a significant effect on the long-term outcomes. Lack of data on medication use in the postoperative period, including anticoagulation use and particulars of the type of valve surgery, limits our ability to draw direct causal conclusions about role of AF. However, our well-characterized, large database of patients undergoing valve surgery with long and complete follow-up provides an opportunity to draw robust conclusions. It should be noted that the identification of AF with increased mortality does not establish a causative relationship. The unambiguous association with worse outcomes is clear from our study.

Summary

For patients undergoing cardiac valve surgery, PPAF and PSAF are associated with longer hospital stay and higher long-term mortality. Prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the relationships among these common arrhythmias and outcomes in patients undergoing valve surgeries.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Levy F,LaLuerveynFt M, Monin JL, et al. Aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis operative risk stratification and long-term outcome: A European multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1466-72.

- Schonburg M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Weinbrenner F, et al. Preexisting atrial fibrillation as predictor for late-time mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing cardiac surgery – a multicenter study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:128-32.

- Bramer S, van Straten AH, Soliman Hamad MA, et al. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation predicts late mortality after mitral valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:2091-6.

- Filardo G, Hamilton C, Hamman B, Hebeler RF Jr, Adams J, Grayburn P. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation and long-term survival after aortic valve replacement surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:474-9.

- El-Chami MF, Kilgo P, Thourani V, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1370-6.

- Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920-5.

- Ahmed A, Perry GJ. Incident atrial fibrillation and mortality in older adults with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:1118-21.

- Khan MN, Jais P, Cummings J, et al. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1778-85.

- STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database data collection forms and specifications. <www.sts.org/sts-national-database/database- managers/adult-cardiac-surgery-database/data-collection> (Accessed April 1, 2010).

- Edwards FH, Peterson ED, Coombs LP, et al. Prediction of operative mortality after valve replacement surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:885-92.

- Filsoufi F, Rahmanian PB, Castillo JG, Scurlock C, Legnani PE, Adams DH. Predictors and outcome of gastrointestinal complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Ann Surg 2007;246:323-9.

- Rahmanian PB, Filsoufi F, Castillo JG, et al. Predicting postoperative renal failure requiring dialysis, and an analysis of long-term outcome in patients undergoing valve surgery. J Heart Valve Dis 2008;17:657-65.

- Ngaage DL, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, et al. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation influence early and late outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:182-9.

- Mariscalco G, Engstrom KG. Postoperative atrial fibrillation is associated with late mortality after coronary surgery, but not after valvular surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1871-6.

- Attaran S, Shaw M, Bond L, Pullan MD, Fabri BM. Atrial fibrillation postcardiac surgery: A common but a morbid complication. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:772-7.

- Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2004;291:1720-9.

- Shariff N, Zelenkofske S, Eid S, Weiss MJ, Mohammed MQ. Demographic determinants and effect of pre-operative angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on the occurrence of atrial fibrillation after CABG surgery. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2010;10:7.

- Nakai T, Lee RJ, Schiller NB, et al. The relative importance of left atrial function versus dimension in predicting atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Am Heart J 2002;143:181-6.

- Osranek M, Fatema K, Qaddoura F, et al. Left atrial volume predicts the risk of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:779-86.

- Vogt PR, Brunner-LaRocca HP, Rist M, et al. Preoperative predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation late after successful mitral valve reconstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998;13:619-24.

- Anselmi A, Possati G, Gaudino M. Postoperative inflammatory reaction and atrial fibrillation: Simple correlation or causation? Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:326-33.

- Canbaz S, Erbas H, Huseyin S, Duran E. The role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation following open heart surgery. J Int Med Res 2008;36:1070-6.

- Elahi M, Hadjinikolaou L, Galinanes M. Incidence and clinical consequences of atrial fibrillation within 1 year of first-time isolated coronary bypass surgery. Circulation 2003;108(Suppl 1):II207-212.

- Abdelhadi RH, Gurm HS, Van Wagoner DR, Chung MK. Relation of an exaggerated rise in white blood cells after coronary bypass or cardiac valve surgery to development of atrial fibrillation postoperatively. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1176-8.

- Kalman JM, Munawar M, Howes LG, et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:1709-15.

- Auer J, Weber T, Berent R, Ng CK, Lamm G, Eber B. Postoperative atrial fibrillation independently predicts prolongation of hospital stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2005;46:583-8.

- Rubin DA, Nieminski KE, Reed GE, Herman MV. Predictors, prevention, and long-term prognosis of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Sep 1987;94:331-5.

- Banach M, Goch A, Misztal M, et al. Relation between postoperative mortality and atrial fibrillation before surgical revascularization – 3-year follow-up. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:20-3.

- Ad N, Barnett SD, Haan CK, O’Brien SM, Milford-Beland S, Speir AM. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation increase the risk for mortality and morbidity after coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:901-6.