Impacts of a Psychosocial Intervention Program in support of adaptation on Canadian Armed Forces military members posted to Europe

Received: 13-Jul-2018 Accepted Date: Jul 23, 2018; Published: 30-Jul-2018

Citation: Clin Psychol Cog Sci Vol 2 No 1 June 2018

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

The Canadian Armed Forces deploy soldiers and members of their families beyond Canada’s borders. In military circles, such deployments are called “OUTCAN postings”. In winter 2010, a Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe (PAPCAFE) was developed from two studies conducted in autumn 2009 and winter 2010, with the goal of identifying factors contributing to early repatriation and determining the psychosocial dynamics in play during the first six months of a posting on European soil. The PAPCFE seeks to complete the psychosocial preparation for the transition from Canada to Europe, and in the medium term cut down on early repatriations. In this study, we conducted two types of program evaluation simultaneously, using a combination of several methods.

Keywords

Psychosocial intervention; Military social work; Canadian Armed Forces; Adaptation.

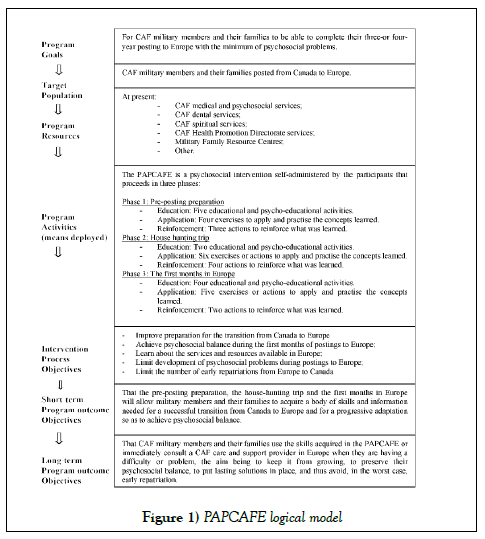

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) deploy soldiers and members of heir families beyond Canada’s borders. In military circles, such deployments are called “OUTCAN postings” (i.e., OUTside CANada). In this paper, we will be dealing with postings to Europe (other than postings to attaché or embassy positions). The administrative component of a Europe posting concerns the steps military members must take to handle moving their personal and family members’ effects. But what about the psychosocial component? How does one leave Canada, one’s family and one’s friends for a period of three to four years? How does one integrate into the new social and professional environment, for some, isolated, with a different language and a different culture. In light of this, are the psycho-educational and preventive measures integrated into the screening process for OUTCAN postings (CAF Instruction 5020-66) able to make the transition from Canada to Europe more accessible and acceptable, so as to reduce the number of psychosocial problems and thus, ultimately, early repatriations? How do these measures contribute to improving the quality of life, employability skills and ability to manage problems of the individuals concerned. In winter 2010, a Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe (PAPCAFE) was developed from two studies conducted in autumn 2009 and winter 2010, with the goal of identifying factors contributing to early repatriation and determining the psychosocial dynamics in play during the first six months of a posting on European soil. The results of the first study identified the key determinants contributing to repatriation as: 1) flaws in the screening process for CAF members and its application; 2) the emergence or development of psychosocial problems; 3) the application of disciplinary or administrative measures (as an indicator of psychosocial imbalance); 4) expectations not fulfilled/met by the posting. The results of the second study show that quality of life, employability skills and the ability to manage reported problems do not vary over the first three months of the posting. Furthermore, the psychological quality of life between the two survey times (October 2009 and January 2010) is relatively stable, and the “physical” and “social relationships” aspects of quality of life as well as the “acquiring social support” and “reframing” aspects of problem-solving abilities have positive effects on the psychological quality of life. The PAPCAFE seeks to complete the psychosocial preparation for the transition from Canada to Europe, and in the medium term cut down on early repatriations. PAPCAFE’s logical model, with its various preventive and psycho-educational components, is presented below in Figure 1.

In response to a problem situation, a psychosocial intervention program like PAPCAFE attempts to improve the social functioning of the individual and help them change the significant elements in the situation [1,2]. Evaluating a psychosocial intervention program allows developing and strengthening awareness and reflection with the aim of judging the program’s merit and value from a perspective of change [3]. In this study, we conducted two types of program evaluation simultaneously, using a combination of several methods. It bears specifying that this is a preliminary evaluation of the PAPCFE and that an exhaustive program evaluation should be produced. Firstly, the evaluation of the initial implementation (formative evaluation) of PAPCAFE consists in adjusting the program and making a judgment about what was achieved vs. what was expected. As Rossi, Lipsey & Freeman [4] put it, the formative evaluation plays two crucial roles: “It gives feedback to the decision-makers so that the program can be improved as quickly as possible and supplements the evaluation of the results or the program’s impact by allowing the results obtained to be interpreted on the basis of the program’s actual implementation” (p.175).

Secondly, the summative evaluation of PAPCAFE consists in determining the extent of the effects arising from implementing the intervention. In fact, it is a matter of measuring the expected changes in military members with reference to the objectives established as the intervention is being designed (objectives of the intervention process). Dessureault and Caron [1] suggest that “the challenge of a summative evaluation is being able to establish with certitude that the effects observed are produced solely by the program” (p. 186). The summative evaluation of PAPCAFE is based on an experimental design where two similar groups (one participating, the other not) were studied. This type of study has not been discussed in a scientific publication and appears to be an innovation in the literature. In order to bring the outlook for PAPCAFE up to date, evaluating the psychosocial intervention has the following objectives: identify the profile of “new arrivals in Europe;” bring out the impacts of the program, in other words, evaluate the level of satisfaction and the quality of the components of the psychosocial intervention and its impacts on the participants; compare the changes between Time t1 and Time t2 in terms of quality of life, employability skills and the ability to manage problems within three groups of military members newly arrived in Europe in 2009 and 2010; analyze the differences in perceptions between a group of participants and two groups of nonparticipants in PAPCFE in terms of their quality of life, employability skills and ability to manage problems in the CAF.

Material and Methods

Population

Out of a total of 330 military members posted to Europe in active posting season 2009 and 2010, 69 voluntarily agreed to take part in our study. Invitations to participate were sent to the members’ CAF E-mail addresses in Canada’s two official languages at the beginning of October 2009 and 2010. This population yielded three groups of military members.

Group 1: Military members posted to Europe during the 2009 active posting season who did not participate in the Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe represent 55.1% (38 military members) of the participants.

Group 2: Military members posted to Europe during the 2010 active posting season who did not participate in the Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe represent 34.8% (24 military members) of the participants.

Group 3: Military members posted to Europe during the 2010 active posting season who did participate in the Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe represent 10.1% (7 military members) of the participants.

Ethics

The protocol of the study and the content of the questions on the surveys were officially approved by the CAF Social Science Research Ethics Board. Information leaflets advised participants of the aim and objective of the research, how it would be conducted, its confidentiality, their right to withdraw at any time, and that the published results would be anonymous. All the participants signed a consent form indicating their free participation in this research.

Methods

The information-gathering tool is a questionnaire in English and French tested on nine individuals (four francophones and five anglophones); time to complete is around 20 minutes. Two surveys were taken, at 3 and 6 months after arrival (Group 1: October 2009 and January 2010; Groups 2 and 3: October 2010 and January 2011). A period of four weeks was allowed for returning the questionnaire. A follow-up was conducted three weeks after the start of the survey. After the confidential capture of data through an anonymous coding system, the collected questionnaires were destroyed. Group 3 also completed a PAPCAFE evaluation form. This tool, an evaluation grid in English and French, was tested on four military members (two francophones and two anglophones) currently posted in Europe; it takes about 30 minutes to complete. It was administered starting on 15 October 2010, the date on which PAPCAFE activities conclude. The participants were given four weeks to complete the form. A follow-up was conducted two weeks after the start of the process. The PAPCAFE evaluation forms were destroyed following confidential data capture.

Data-Gathering Tools

Questionnaire survey

Five groups of variables were collected.

1) The socio-demographic characteristics of the military members

These are the age, sex, rank (non-commissioned member, officer), element (sea, land, air), years of service, location of posting, number of postings outside Canada, marital status, number of children, mother tongue, education and income level.

2) Sense of belonging to the CAF

This concerns how one perceives one’s sense of belonging, measured by a four-point question allowing evaluation of intensity (Very little to Very much). Level of agreement was also evaluated using four questions with a four-point response scale (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) about the CAF as a good place to work, current job satisfaction, career satisfaction and commitment to the success of the CAF.

3) WHOQOL-Bref measurement scales for four quality of life domains

WHOQOL-Bref is an abbreviated version (24 items) of WHOQOL-100. It contains 24 items covering four domains of quality of life: physical health (7 items), psychological (6 items), social relationships (3 items) and environment (8 items). Responses to the questions lie on a five-point scale for intensity (Not at all extremely), ability (Not at all … Completely), frequency (Never Always) and assessment (Very dissatisfied/Very poor Very satisfied/ Very good).

4) Scale of employability skills

In the version used, the scale consists of 15 items with a four-point response scale (Not at all A great deal) allowing two categories to be measured: the acquisition and the application of skills.

5) The Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale (F-COPES)

The version of the scale used contains 25 items divided into four domains: 1) acquiring social support (9 items), 2) reframing (8 items), 3) mobilizing family to acquire and accept help (4 items), and 4) passive appraisal (4 items). The F‑COPES has a five-point response scale measuring degree of agreement with the items (Strongly disagree Strongly agree). The spiritual support domain was not part of our study.

PAPCAFE evaluation form

This form was designed to gather both qualitative and quantitative data. The form evaluates 11 aspects of PAPCAFE, including logistics, the goal, intervention process objectives, short-term outcome objectives, long-term outcome objectives, phases, time, duration, strengths and areas in need of improvement. Some aspects, such as “intervention process objectives,” “PAPCAFE phases” and “time and duration of PAPCAFE” contain more than one question to answer. Except for such aspects as “strengths,” “areas to improve” and “other comments, remarks, views” which are open-ended questions, all the other aspects contain a quantitative and a qualitative portion. The data in the quantitative portion is gathered using a five-point scale (from Very poor to Very good) and a Likert scale (from Totally Disagree to Totally Agree). Gathering qualitative data is an open question for this area and allows clarifying the quantitative portion.

Statistical Analysis

First of all, the sociodemographic variables from the two data collections (new arrivals 2009 and new arrivals 2010) were subjected to a descriptive analysis, making a distinction between those who took the PAPCAFE and the rest. The qualitative variables were described using percentages, and the quantitative variables using means and standard deviations. The three groups were compared using Chi-squared tests for the qualitative variables and ANOVA tests for the continuous variables. Secondly, the PAPCAFE Evaluation Form results were put through a descriptive analysis. The quantitative data was described with means and standard deviations. The responses to open-ended questions were given a discursive analysis. Thirdly, the WHOQOL-Bref, employability skills and F-COPES scores were calculated using the methods described in the reference literature. The higher the score, the better the quality of life. For each of the groups of participants described above, we compared the scores at Times t1 and t2 using Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. Use of these two tests is justified by the fact that the score distribution is often skewed and that the assumption of normality on which the t-test is based is sometimes doubtful. Finally, for each of the WHOQOL-Bref scores, employability skills scores and problem-management scores, we developed a mixed linear model to account for the correlations between the data on the same individual from Times t1 and t2. The independent variables are the time and the group to which the individuals surveyed were assigned. The statistical analyses were processed with PASW 18 software. The qualitative data was processed with NVivo 8 software.

Results and Discussion

The participation rate in the longitudinal study was 20.7%, or 69 of the 330 military members posted to Europe in 2009 and 2010.

The socio-demographic profile of participants and non-participants in PAPCFE

The “new arrivals” consisted of 39 military members (October 2009), 32 (October 2010) at time 1, and 38 military members (January 2010), 31 (January 2011) at time 2. At times 1 and 2, the military members participating concerned only the cohort of 38 (in 2009–2010) and of 31 (2010–2011). Of the respondents at Times t1 and t2, 50.7% were officers and 49.3% noncommissioned members, with an average of 20.4 years of service in the CAF (5 years; 38 years). They served in the land (47.8%), air (43.5%) and sea (8.7%) elements. Of the total, 82.6% were men and 17.4% women, with an average age of 41.6 years (23 years; 56 years), married (81.2%), with one to three children (62.3%) and having completed an education at the secondary school (20.3%), college or professional (29%) and university (50.7%) level. Per household, 50.7% had an annual salary of over $100,000 before taxes. Mother tongue was English (60.9%) and French (39.1%). Locations of their posting in Europe were: Germany 52.2%, Belgium 21.7%, the United Kingdom 14.5%, and 11.6% other (the Netherlands, Turkey, Italy and Norway) (Table 1).

| Variables | Groups | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 New Arrivals 2009 N=38 % (strength) |

Group 2 New Arrivals 2010 N=24 % (strength) |

Group 3 New Arrivals 2010 (PAPCAFE) N=7 % (strength) |

Groups 1-2-3 N=69 % (strength) |

|||

| Rank | Officer | 29 (20) | 14.5 (10) | 7.2 (5) | 50.7 (35) | 0.360 |

| NCM | 26.1 (18) | 20.3 (14) | 2.9 (2) | 49.3 (34) | ||

| Element | Land | 30.4 (21) | 13 (9) | 2.9 (2) | 46.4 (32) | 0.218 |

| Air | 21.7 (15) | 15.9 (11) | 7.2 (5) | 44.9 (31) | ||

| Sea | 2.9 (2) | 5.8 (4) | 0 (0) | 8.7 (6) | ||

| Force | Regular | 55.1 (38) | 34.8 (24) | 10.1(7) | 100 (69) | .a |

| Reserve | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Location Of Posting | Germany | 29.0 (20) | 15.9 (11) | 7.2 (5) | 52.2 (36) | 0.890 |

| Belgium | 13.0 (9) | 8.7 (6) | 1.4 (1) | 23.2 (16) | ||

| United Kingdom | 5.8 (4) | 5.8 (4) | 1.4 (1) | 13.0 (9) | ||

| Other | 7.2 (5) | 4.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 13.0 (9) | ||

| Civil Status | Married | 40.6 (28) | 30.4 (21) | 10.1 (7) | 81.2 (56) | 0.162 |

| Not married | 14.5 (10) | 4.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 18.8 (13) | ||

| No of children | 0 | 21.7 (15) | 10.1 (7) | 4.3 (3) | 36.2 (25) | 0.460 |

| 1 | 10.1 (7) | 8.7 (6) | 0 (0) | 18.8 (13) | ||

| Sex (%) | 2 | 15.9 (11) | 8.7 (6) | 1.4 (1) | 26.1 (18) | |

| 3 or more | 7.2 (5) | 7.2 (5) | 4.3 (3) | 18.3 (13) | ||

| Languages Spoken In The Home | French | 18.8 (13) | 17.4 (12) | 2.9 (2) | 39.1 (27) | 0.386 |

| English | 36.2 (25) | 17.4 (12) | 7.2 (5) | 60.9 (42) | ||

| Highest Level of Education Achieved | Secondary | 7.2 (5) | 10.1 (7) | 2.9 (2) | 20.3 (14) | 0.397 |

| Vocational or college | 15.9 (11) | 11.6 (8) | 1.4 (1) | 29.0 (20) | ||

| University | 31.9 (22) | 13.0 (9) | 5.8 (4) | 50.7 (35) | ||

| Annual Income Before Taxes | Less than $59,999 | 7.2 (5) | 8.7 (6) | 0 (0) | 15.9 (11) | 0.162 |

| $60,000 to $99,999 | 14.5 (10) | 14.5 (10) | 2.9 (2) | 31.9 (22) | ||

| Over $99,999 | 31.9 (22) | 11.6 (8) | 7.2 (5) | 50.7 (35) | ||

| Don’t know | 1.4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.4 (1) | ||

| Age (yrs) (ANOVA 1 Test) | 40.8 | 42.3 | 41.1 | 41.4 | 0.770 | |

| Years of Service (yrs) (ANOVA 1 Test) | 19.4 | 21.6 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 0.642 | |

p*: Significance level of Chi square test (p<0.05).

.a: a constant, hence no statistical value calculated.

Table 1: Socio-demographic variables of military members participating in the research.

Evaluation of PAPCAFE by the participants

Participant satisfaction with the psychosocial intervention was expressed in the positive attitudes in most of the statements put forward: on a scale of 1 to 5, the values lie between 3 (Neutral/Neither poor nor good) and 4 (Agree/Good) (Table 2). Satisfaction is somewhat negative (values between 2 (Disagree) and 3 (Neutral) on a scale of 1 to 5) about the “PAPCAFE intervention process objectives,” which are (D) “to limit the number of psychosocial problems during postings to Europe”, and (E) “to limit the number of early repatriations from Europe to Canada” (Table 2). The satisfaction of PAPCAFE participants was most concentrated around the “PAPCAFE intervention process objectives, which are: (A) “improve preparation for the transition from Canada to Europe” (3.85) and (C) “find out about the services and resources available in Europe” (3.85), “the point during the Europe posting process that the PAPCFE is conducted” (3.85) and “duration in terms of time investment” (3.85). The statement “the point during the Europe posting process that the PAPCAFE is conducted” exhibits the lowest standard deviation (0.378), thus showing the level of agreement among participants. Among the “PAPCAFE intervention process objectives,” (D) — “limit the number of psychosocial problems during postings to Europe” (2.85) — is the proposition with the lowest average and the lowest standard deviation (0.378).

| Statement | N | Min | Max | Moy | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistics of PAPCAFE 1 | 7 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.714 | .951 |

| Purpose of PAPCAFE 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.286 | .951 |

| Purpose of intervention 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .787 |

| A) Preparation for transition 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 3.857 | .690 |

| B) Psychosocial balance 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .535 |

| C) Learning about available resources 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 3.857 | .690 |

| D) Limiting problems 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 2.857 | .378 |

| E) Limiting repatriations 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.857 | .690 |

| Outcome-linked objectives (short-term) 2 | 7 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.143 | 1.069 |

| Outcome-linked objectives (long-term) 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.143 | .378 |

| General usefulness of phases 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .535 |

| Usefulness of Phase 1 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .787 |

| Usefulness of Phase 2 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .787 |

| Usefulness of Phase 3 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.285 | .756 |

| All phases 2 | 7 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.429 | .787 |

| When the PAPCAFE was conducted 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.857 | .378 |

| Duration of PAPCAFE 2 | 7 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 3.857 | .690 |

| Overall evaluation of PAPCAFE 1 | 7 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.571 | .535 |

1Five-point scale: 1=Very poor; 2=Poor; 3=Neither poor nor good; 4=Good; 5=Very good

2Five-point Likert Scale: 1=Strongly disagree; 2=Disagree; 3=Neither Agree nor Disagree; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly agree

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of the PAPCAFE evaluation form open-ended questions

The logistics of PAPCFE

Two participants question the relevance of inviting military members by E-mail: “with the torrent of E-mails we get every day, I am not sure this is the best way to invite military members to take part in this program”; “On the whole, the logistics were very good, but it would be simpler for the CO, the medical officer or the social worker in Canada to issue the invitation to the participants, and not by E-mail”.

The goal of PAPCFE

One participant wonders whether the goal of PAPCAFE is clearly presented in the PAPCAFE Participant’s Guide: “Not sure this goal is clearly communicated. I understood this was a study to determine potential eligibility of candidates and as such would be used as a screening process or refinement”.

The objectives of the intervention process

According to three participants, PAPCAFE would enable improving preparation for the transition from Canada to Europe and to find out about the services and resources available in Europe: “The strength of the program is that it was very helpful to us, both individually and as a family, in planning for our posting”; “The CAF Europe Resources List is definitively an asset”; “I can easily understand how a Canadian wife and children would make for some definite challenges to a new member to CAF Europe and having a system like this in place will be an asset” Four of the participants felt that PAPCAFE would have little impact on limiting psychosocial problems during postings in Europe and on the number of early repatriations from Europe to Canada: “For myself, I do not think the PAPCAFE has made any difference at all”; “it’s possible that this intervention could help, but when it comes to reducing psychosocial difficulties or early repatriations, I think more would be needed”; “I really do not think that the intervention can prevent psychosocial issues and early repat”; “to achieve these objectives, the Outcan Screening would have to be applied correctly… and military members with serious problems should stay in Canada”.

Short-term outcome objectives

For two participants, the personal history of military members to do with previous OUTCAN posting experiences and marital status during the posting should be considered: “My case is not standart posting type. First months, I was IR (imposed restriction), and I am married to former local German, with family in the area. Prior posting here (1990-1994) make things much easier to transition to. I did find the IR portion “painful” ”; “… this is my second posting to Germany during my time in the military (as well as being born here). I was fairly aware of what life in Germany was like and the associated challenged that might arise. Also my wife is German and it was a big consideration to get posted back here.. her being German has prevented some of the issues that others may have as their spouse tries to transition to life in a new environment. We do not have any children either”.

Phases of the PAPCAFE

The participants had little to say about the three phases of PAPCAFE. One found it difficult to complete all the activities of Phase 3: “For us, Phase 3 is the most relevant and practical in helping us to get a good start with the deployment, but with all the things to do when you get there, it was hard for us to complete all the points properly”. Another stated that the sponsor system (Para 3.3.1 of the Phase 2 Education section) should be improved: “I think that anyone that is going to be a sponsor should have some short duration formal training to allow them to make the transition easier for those that they are supposed to assist. I know my own sponsor did a much better job on helping me out than what I have heard from others”.

Time and duration of PAPCAFE

According to the comments of two participants, the best time for running PAPCAFE would be during the posting process (between April and October): “the program was run exactly at the right time, given my circumstances. I got my posting message at the end of March ideally, the program could begin as early as February to give us more time to complete the activities One suggestion is that the military members who receive their posting message receive the inivitation to participate in the program at the same time”; “no doubt for me that the PAPCAFE is put in place at the right time in the Outcan process”. One participant states that more time should be allotted for completing the PAPCAFE: “I’m sure I’d have needed over 20 hours to complete all the exercises to the letter I find this part vague… and also the fact that the program runs for 8 months. It might be useful for there to be 2 or 3 encounters with the participants during the program”.

PAPCAFE strengths and areas needing improvement

The comments and recommendations made about the PAPCAFE, while varied, appear fairly positive: “I think the PAPCFE could be a very useful tool to transition to life in a new location overseas, some parts need to be developed but I understand that could take time. Why the PAPCFE does not become mandatory for all CAF members posted outside Canada? Food for thought!”; “Thanks for making the effort to help others find their way in their transition to life over here”; “Very good program! While it is hard at this stage to measure the consequences for me and my family, I’m quite sure taking part couldn’t hurt.”; “Capt Blackburn, impressive work! I really appreciated that PAPCAFE is flexible (you can go at your own pace), covers a variety of aspects of a posting outside Canada, and deals with the personal/ individual and family aspects of the deployment (how you’re feeling). I hope your social-worker colleagues in Canada will be able to help you establish PAPCAFE”. Lastly, it was also proposed that the PAPCAFE Participant’s Guide undergoes linguistic revision: “The English version needs to be reviewed by an English native speaker. I found several translation mistakes”. The perception of quality of life, employability skills and the ability to manage problems by participants and non-participants in PAPCFE.

Group 1: New arrivals in APS 2009 and non-participants in PAPCFE

Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test show that there is no significant difference between Times t1 and t2 for any of the scores (Table 3).

| Scale | Time 1 N=38 |

Time 2 N=38 |

p1 | p2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-Bref Dimension 1: Physical Health Dimension 2: Psychological Dimension 3: Social relationships Dimension 4: Environment |

81.7 77.1 69.3 78.9 |

81.1 75.8 69.5 77.1 |

0.709 0.347 0.921 0.208 |

0.630 0.204 0.856 0.300 |

| Employability Skills Dimension 1: Acquisition Dimension 2: Application |

75.7 82.6 |

77.1 83.4 |

0.440 0.678 |

0.489 0.705 |

| Ability to Manage Problems Dimension 1: Social support Dimension 2: Reframing Dimension 3: Mobilizing family… Dimension 4: Passive appraisal |

51.3 74.1 54.0 77.1 |

53 76.7 56.3 74.6 |

0.439 0.124 0.378 0.265 |

0.435 0.154 0.323 0.344 |

p1: Significance level of Student’s t-test: *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

p2 : Significance level of Wilcoxon non-parametric test *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

Table 3: Scoring of scales (0-100) from October 2009 and January 2010

Group 2: New arrivals in active posting season 2010 and non-Participants in PAPCAFE

Results for the perception of the “Acquisition” aspect of employability skills show a variation of -6.6 between t1 (80.5) and t2 (73.9). Student’s t-test (p=0.013) and the Wilcoxon test (p=0.021) confirm that this difference is statistically significant. A variation of 4.3 is also observable for the “Passive Appraisal” aspect of the ability to manage problems: t1 (74.3) vs. t2 (78.6). Both Student’s t-test (p=0.028) and the Wilcoxon test (p=0.033) show that the results are statistically significant. Finally, the “Reframing” aspect of the ability to manage problems yields results varying by -4.0 from t1 (76.6) to t2 (72.6). Only the Wilcoxon non-parametric test confirms the significance (p=0.018) (Table 4).

| Scale | Time 1 N=24 |

Time 2 N=24 |

p1 | p2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-Bref Dimension 1: Physical Health Dimension 2: Psychological Dimension 3: Social relationships Dimension 4: Environment |

79.3 79.2 74.7 83.1 |

80.4 76.9 73.3 77.0 |

0.659 0.353 0.660 0.365 |

0.316 0.227 0.646 0.637 |

| Employability Skills Dimension 1: Acquisition Dimension 2: Application |

80.5 88.5 |

73.9 85.0 |

0.013* 0.148 |

0.021* 0.078 |

| Ability to Manage Problems Dimension 1: Social support Dimension 2: Reframing Dimension 3: Mobilizing family… Dimension 4: Passive appraisal |

56.8 76.6 61.1 74.3 |

53.7 72.6 57.1 78.6 |

0.370 0.077 0.169 0.028* |

0.211 0.018* 0.155 0.033* |

p1: Significance level of Student’s t-test: *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

p2: Significance level of Wilcoxon non-parametric test *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

Table 4: Scoring of scales (0-100) from October 2010 and January 2011 (non-participants)

Group 3: New arrivals in active posting season 2010 and participants in PAPCAFE

With only one exception, all the results shown in Table 5 are not statistically significant. Only the “Application” aspect of employability skills shows a variation of 5.7 from t1 (84.8) to t2 (90.5). The significance level of Student’s t-test (p=0.028) and the Wilcoxon test (p=0.027) confirms that these two results are statistically significant.

| Scale | Time 1 N=7 |

Time 2 N=7 |

p1 | p2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHOQOL-Bref Dimension 1: Physical Health Dimension 2: Psychological Dimension 3: Social relationships Dimension 4: Environment |

88.8 79.2 70.2 85.7 |

84.7 80.4 70.2 86.6 |

0.330 0.752 1.000 0.604 |

0.336 0.750 0.891 0.589 |

| Employability Skills Dimension 1: Acquisition Dimension 2: Application |

72.1 84.8 |

76.8 90.5 |

0.212 0.028* |

0.207 0.027* |

| Ability to Manage Problems Dimension 1: Social support Dimension 2: Reframing Dimension 3: Mobilizing family… Dimension 4: Passive appraisal |

51.9 71.4 70.5 87.2 |

55.6 75.0 75.0 81.3 |

0.310 0.413 0.489 0.190 |

0.269 0.684 0.680 0.112 |

p1: Significance level of Student’s t-test: *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

p2: Significance level of Wilcoxon non-parametric test *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

Table 5: Scoring of scales (0-100) from October 2010 and January 2011 (participants)

Impacts of PAPCFE

All the results shown in Table 6 are not statistically significant after the mixed model was applied.

| Reliability | Time | Interaction Time X Participation in PAPCAFE 2010 |

Participant Standard deviation | Residual Standard deviation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=7) | No (N=62) | ||||||||||

| Est | Est | p(1) | Est | p | Est | p | Est | Est | |||

| WHOQOL-Physical Health | 81.6 | -.325 | 0.799 | -.367 | 0.799 | 0 | - | 57.7 | 51.3 | ||

| WHOQOL-Psychological | 78 | -1.732 | 0.161 | 3.386 | 0.331 | 0 | - | 69.9 | 47.3 | ||

| WHOQOL-Social Relationships | 71.3 | -.364 | 0.837 | 0.023 | 0.996 | 0 | - | 195.8 | 98.7 | ||

| WHOQOL- Environment | 81.1 | -3.865 | 0.131 | 7.744 | 0.247 | 0 | - | 114.2 | 205.5 | ||

| ES- Acquisition | 77 | -1.609 | 0.272 | 5.392 | 0.319 | 0 | - | 268 | 66.3 | ||

| ES- Application | 84.7 | -.926 | 0.489 | 6.657 | 0.89 | 0 | - | 146.9 | 54.3 | ||

| PMS- Social support | 52.9 | -.931 | 0.615 | 4.539 | 0.384 | 0 | - | 172.4 | 97.1 | ||

| PMS – Reframing | 74.9 | 0.013 | 0.992 | 2.306 | 0.552 | 0 | - | 101.1 | 57.2 | ||

| PMS- Mobilizing family | 58.2 | -.623 | 0.749 | 9.067 | 0.108 | 0 | - | 245.1 | 117 | ||

| PMS- Passive appraisals | 77.2 | -.228 | 0.884 | -2.509 | 0.581 | 0 | - | 162.8 | 76.8 | ||

p1: Significance level of Student’s t-test: *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

p2 : Significance level of Wilcoxon non-parametric test *p<0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001.

Table 6: Modelling Domain Evolution in WHOQOL-Bref, Employability Skills and Problem-Management Skills between T1 and T2 Based on Participation in PAPCAFE-2010 (mixed models)

Limits of the Study

Survey by questionnaire

The approach we used (by E-mail) to contact CAF members newly posted to Europe during the 2009 and 2010 active posting seasons was not the most effective. First of all, CAF military members are swamped by countless E-mails of every kind and, based on the read rate for our invitation to our questionnaire surveys (123 E‑mails read out of 176 sent in 2009 and 107 E-mails read out of 169 sent in 2010), it appears that we did not succeed in contacting all the new arrivals. We have also learned that the CAF’s DWAN (Defence Wide Area Network) and DIN (Defence Internal Network) systems do not allow E-mails to be received and sent between all types of E-mail address. E‑mails from such Internet sites as Hotmail, Yahoo and Google are not always allowed through the anti-virus protection systems, which means that the participant does not receive our E-mails or we are not able to receive theirs. By the same token, E-mails that we sent to new arrivals from the DWAN and DIN were classified as confidential (CCI). A few weeks after the survey began, we learned that NATO’s E-mail system does not accept confidential E-mails, as a result, several new arrivals never got our invitations to take part in our questionnaire survey. It is also interesting to note that our clinical observations as head of the Psychosocial Services and Mental Health Department at the Geilenkirchen Detachment of the CAF Health Services Centre (Ottawa) are not consistent with the results of the questionnaire surveys. In fact, September, October and November are generally very busy months for our services. Several new arrivals in Europe experience difficulties with adapting, with culture shock and with anger and stress management. This leads us to form the hypothesis that new arrivals experiencing difficulties during the first months of a posting in Europe tend not to participate in this type of questionnaire survey and especially if it concerns quality of life and the ability to manage problems.

Secondly, it must be acknowledged that the low participation rate in this study (20.7%, or 69 participants out of a possible 330) limits the significance of its results. In our view, the chief explanation is that the CAF is an organization made up mostly of males (85.3% men versus 14.7% women for all Canadian military members) and they tend not to participate in this type of study [5]. It is recognized that men are less inclined to participate in questionnaire surveys than women, mainly because they do not like to talk about themselves and give their personal opinion; [6] Van Loon, Tijhuis, Picavet, Surtees, & Ormel [7].

Psychosocial intervention

We have encountered difficulties in recruiting for the PAPCAFE, which explains the low number of participants. The chief explanation lies in the challenges with recruiting the participants, that is, military members selected for a posting in Europe. The Canadian Armed Forces set military career managers no deadlines for producing a posting message. As a result, the selection period runs from autumn to spring before the active posting season. Given that the PAPCAFE needs to run between April and September, several potential participants will not have received their posting message when the invitations to participate in the program are sent out. Setting a deadline would facilitate participant recruitment. Another solution would be to make the PAPCAFE an integral part of the Screening for Outside of Canada Postings, that is, obligatory for all military members selected for a posting in Europe. Our research provides a better understanding of the process whereby military members and their families adapt to a new cultural and socio-professional environment, knowledge that could prove useful well beyond the military domain and lead to avenues of intervention for the CAF. Our study indicates that the Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe (PAPCAFE) fills a gap in the preparation of military members deployed to Europe. Based on the majority of the statements (14 out of 16), the seven participants in our study assessed the PAPCAFE positively. On the other hand, they consider that the PAPCAFE has no effect on limiting psychosocial problems and on early repatriations.

The work performed, including the protocol, the data-gathering instruments and hence the statistical results comparing a group of participants and a group of non-participants in the PAPCAFE do not allow one to conclude that the program has made a significant contribution to the transition of military members from Canada to Europe for those who participated. A longitudinal study would permit validating the direct effects of the PAPCAFE. In addition, a complete evaluation of the PAPCAFE through an integrating model (before/during/after phases) would be something to consider for measuring its relevance.

Outlook for PAPCAFE

Program evaluation: Evaluability assessment, formative evaluation and summative evaluation of PAPCAFE

A complete evaluation of PAPCAFE would permit validating its usefulness and making improvements with the aim of adjustments/corrective measures as the outcome. To do this, a complete structure for program evaluation must be instituted. This structure would have to be put in place down the road, as, according to the literature, for a program to be evaluable, it must have reached a level of maturity, have been developed, applied and adjusted [8]. For Turcotte & Tard [3]: “Evaluation is primarily a critical look at action. Evaluation is making a judgment about the intervention in the light of relevant information with the goal of making a decision. When evaluating, one is therefore judging the merit and worth of an intervention or a program… from a perspective of change” (p. 327–328). The scientific literature permits a distinction between evaluating the intervention and evaluating the program. Evaluation of a program is based on diagnosing, processing and evaluating the results. Alain and Dessureault [9] elaborate on this, stating: “any planned and considered intervention must be part of a program that provides support, material and human assistance, resources, contacts, theoretical and legal frameworks, and all other considerations, in order for our intervention with an individual or group of individuals to take place under the best possible conditions: success and coherence.” (p. 3). Before an evaluation framework can be established, one must conduct an evaluability assessment of the program. This preliminary assessment consists in establishing whether the program is at a sufficient level of development, stability and maturity to permit an evaluation [8]. This evaluability assessment is based on three conditions: 1) the program must be clearly articulated; 2) the program must have precise objectives; 3) a logical link must exist between the objectives, the intended outcomes and the program [3]. This is, of course, the first phase of evaluation the PAPCAFE needs to undergo. After that, the evaluation of PAPCAFE needs to be done from two standpoints. Firstly, the evaluation of how the program is proceeding, called the formative evaluation, is done during the intervention and consists in measuring how the program is set up and conducted. “The formative research relies on the available information on the program and uses various data collection methods to describe the activities of the program, to identify its results and determine the nature of the problems to solve” [10]. The formative evaluation also looks at the constraints and influence of the environment on the program’s activities and effects. In short, the formative evaluation contributes to applying adjustments during the course of the program to enhance its constituent elements and promote the achievement of the desired results [3]. Secondly, the evaluation of the effects or results, called the summative evaluation, takes place at the end of the program and consists in measuring the effects or outcomes for the participants. “The evaluation of the effects consists in establishing a causal link between the program and the changes observed in the target group or population The purpose of this strategy is to determine what impacts a program has, both positive and negative” [1]. The summative evaluation enables measuring two aspects of the program: it quantifies changes and identifies their source. Ultimately, the summative evaluation enables one to judge the program’s effectiveness, in other words, its ability to achieve its intended objectives and and its efficiency (the results produced by the program versus the costs involved) [3]. It is recognized that a summative evaluation offers less flexibility than a formative evaluation. In both cases, a broad array of data methods may be used. For the formative evaluation, documentary analysis of written material, analysis of administrative data, interviews, observation and surveys or questionnaires are some of the methods favoured. As regards the summative evaluation, measuring change may be done with standardized instruments such as knowledge tests, measurement scales and qualitative interviews. Measuring attribution of the changes is done through experimental, quasi-experimental or single-metric approaches. In the end, “the choice of methods will thus be based, in order, on prioritized evaluation issues, a chosen approach, the resources available for performing the evaluation and, necessarily, the scope of the program ” [11]. The evaluation of PAPCAFE we have conducted has something of both a formative and a summative evaluation; it is a preliminary evaluation of the program. With a view to the CAF adopting the PAPCAFE, evaluation procedures must be put in place to assess the evaluability, implementation and process of the program. Through a review of the literature, we found that few program evaluations have been conducted within the CAF. However, the Evaluation of the Canadian Forces Grievance Board Review of Military Grievances Program conducted in 2010 is a concrete example of a summative evaluation based on program relevance and performance. In fact, it is a summative evaluation covering a five-year period from January 2005 to December 2009, which highlighted the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the program [12]. The theoretical and methodological underpinnings of this research could be applied to the evaluation of PAPCAFE. The Comprehensive Soldier Fitness Program launched in October 2009 by the United States Army [13] is: “A structured, long term assessment and development program to build resilience and enhance the performance of every Soldier, Family member and DA civilian” [13]. The program’s vision is: “An Army of balanced, healthy, self-confident Soldiers, families and Army civilians whose resilience and total fitness enables them to thrive in an era of high operational tempo and persistent conflict” [13]. One of its objectives is to improve the soldiers’ military readiness and performance. To do this, the program focuses on five domains: physical, emotional, social, family and spiritual. Although the program has already been the target of criticism, mainly for its cost (US $117 million) and the fact that it is not based on scientific evidence it would be useful to note the evaluation framework put in place to highlight the quantified changes and their attribution [14]. This framework could prove useful in developing one for the PAPCAFE, as the programs exhibit some similarity in their theoretical framework, their objectives and their target populations.

Perceptions of military members as an indicator of transition and functioning

The transition from Canada to Europe, and progress during the posting, are two important periods in the deployment to Europe. Although the majority of the results of our study are not statistically significant, they nevertheless allow us to establish a method of measuring the participant’s subjective perception of their quality of life, employability skills and ability to manage problems in their new cultural and socioprofessional environment. These three concepts are indicators of the quality of the transition to and progress to Europe of military members. According to Veterans Affairs Canada, [15] “problems experienced as a result of a major change of life or career can lead to more serious and sometimes chronic problems” (p. 1). There is therefore reason to believe that perception of the quality of life, skills such as those concerning employability, and the ability to manage problems such as coping all have their effect on any transitional process and hence in particular on the transitional process that constitutes a posting (from Canada to Europe), on its course, the management of psychosocial problems that may arise during the posting, and on early repatriation, if necessary. The Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs [16] recognizes the importance that projects promoting quality of life can have on readiness. We are therefore proposing a longitudinal study that would follow the progress of a military member throughout a posting through annual follow-ups that would yield the necessary body of information for putting services and resources in place that would meet the genuine needs of military members and their families as they live and work in Europe.

Conclusion

Our research provides a better understanding of the process whereby military members and their families adapt to a new cultural and socio-professional environment, knowledge that could prove useful well beyond the military domain and lead to avenues of intervention for the CAF. Our study indicates that the Preventive Action Program for CAF Military Members Posted to Europe (PAPCAFE) fills a gap in the preparation of military members deployed to Europe. Based on the majority of the statements (14 out of 16), the seven participants in our study assessed the PAPCAFE positively. On the other hand, they consider that the PAPCAFE has no effect on limiting psychosocial problems and on early repatriations. The work performed, including the protocol, the data-gathering instruments and hence the statistical results comparing a group of participants and a group of nonparticipants in the PAPCAFE do not allow one to conclude that the program has made a significant contribution to the transition of military members from Canada to Europe for those who participated. A longitudinal study would permit validating the direct effects of the PAPCAFE. In addition, a complete evaluation of the PAPCAFE through an integrating model (before/ during/after phases) would be something to consider for measuring its relevance.

REFERENCES

- Dessureault D, Caron V. The more traditional perspective of the measurement of results: Elements of method, the transition from scientific research to its adaptation to the realities of field research and evaluation of the effects of a program. In M. Alain, & D. Dessureault (Eds). Develop and evaluate psychosocial intervention programs. 2009; 177-193.

- Laframbroise J. L’intervention psychosociale, Revue professionnelle Défi jeunesse, Retrived from Centre jeunesse de Montréal website. 2011.

- Turcotte D, Late C. Intervention Evaluation and Program Evaluation. In R. Mayer, F. Ouellet, M-C. Saint-Jacques, D. Turcotte, & collaborators (Eds.). Research Methods in Social Intervention, Boucherville, QC: Gaëten Morin Editor. 2000; 327-358

- Rossi PH, Lipsey MH, Freeman HE. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach, 7th edition, Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage Publications. 2004.

- Park J. A profile of the Canadian Forces, Perspectives, Statistics Canada – Catalogue No 75-001-X, 2008; 17-30.

- Dunn KM, Jordan L, Lacey RJ, et al. Patterns of consents in epidemiologic research: Evidence from over 25,000 respondents, American Journal of Epidemiology, 2004; 159:1087-1094.

- Van Loon AJM, Tijhuis M, Picavet HSJ. Survey non-response in the Netherland: Effects on prevalence estimates and associations. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003; 13: 105-110.

- Potvin P, Evaluability elements and criteria for a Psychosocial Intervention Program. In M. Alain, & D. Dessureault (Eds.), Developing and Evaluating Psychosocial Intervention Programs, Québec, QC. Presses of the University of Quebec. 2009; 01-113.

- Alain M, Dessureault D. Developing and Evaluating Psychosocial Intervention Programs, Québec, QC: University of Quebec Press. 2009.

- Lecomte, R, Rutman L. Introduction to evaluative research methods, Quebec, QC: Université Laval Press. 1982.

- Joly J, Touchette L Pauze R. The formative and summative dimensions of program implementation evaluation: a combination of objective and subjective perspectives in relation to evaluation models based on program theory. In M. Alain, & D. Dessureault (Eds.). Develop and evaluate psychosocial intervention programs. Quebec, QC: Presses of the University of Quebec. 2009; 117-144.

- Public Works & Government Services of Canada. Evaluation of the CFGB Review of Military Grievances Program. 2010.

- United States Army, Comprehensive Soldier Fitness. 2011.

- McCarthy J, Comprehensive soldier fitness: A holistic approach to warrior training. The Psychology of Wellbeing. 2010.

- Veteran Affairs Canada, Assistance Services. 2011.

- Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs, Facing our responsibilities. The state of readiness of the Canadian Forces. 2011.