Investigation of antimicrobial peptide activity against amastigote forms of Leishmania major

Received: 21-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. PULJMBR-22- 5959; Editor assigned: 23-Dec-2022, Pre QC No. PULJMBR-22- 5959 (PQ); Accepted Date: Jan 13, 2023; Reviewed: 28-Dec-2022 QC No. PULJMBR-22- 5959 (Q); Revised: 30-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. PULJMBR-22- 5959 (R); Published: 15-Jan-2023, DOI: 10.37532/puljmbr.2023.6(1).24-27

Citation: Roshan ME. Investigation of antimicrobial peptide activity against amastigote forms of Leishmania major . J Mic Bio Rep. 2023;6(1):24-27.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major is the most common type of disease in Iran. Conventional anticoagulants have been used in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis for a long time, but drug resistance and some serious side effects have been reported. Therefore, the discovery and development of new therapeutic candidates is needed. Peptide CM11 is one of these peptides whose antibacterial activity has been proven. This peptide is a short cecropin-melittin hybrid peptide obtained through a hybrid sequencing method. The aim of this study is to evaluate the anti-leishmanial activity of CM11 platelets against amastigote forms of Leishmania major. In this research, amastigote forms of Iranian Garlic L. major (MRHO/IR /75/ER) were cultured in the presence of different molar concentrations of methylantimony (glucanthium) to find the most suitable concentration of glucanthium in comparison with L. major amastigotes, then the anti-leishmania activity Different concentrations of CM11 peptide (8 μM, 16 μM, 32 μM and 64 μM) for 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours were examined by DAPI staining. In addition, MTT was used to determine the cytotoxic effects of CM11 peptide on mouse fibroblast cells. The results showed that CM11 peptide has an antimicrobial effect against the Iranian isolate of L. major in laboratory conditions. CM11 peptide seems to have significant potential as a new anti-leishmanial agent

Keywords

Amastigote; CM11 peptide; Leishmania major; Parasite

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is an infectious disease of humans and animals caused by different species of the genus Leishmania and transmitted by the sting of female bees [1]. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is one of the important health problems in tropical and subtropical countries around the world as Iran [2]. Iran is one of the 10 countries in the world with the most cases of CL [3]. CL is clinically seen in two types, including the rural type (wet wound) and the urban type (dry wound). Intestinal cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. major is considered Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ZCL). ZCL is endemic in northeastern, southern, and central Iran, and approximately 75% of CL reported in Iran have a zoonotic type [4,5]. The most common treatment is based on the use of anti-inflammatory compounds, including methylmolar antimony (glutamine) and sodium acetobogluconate ((Pentostam). ®) which is recognized as the first-line treatment in most parts of the world. However, in recent years, the effectiveness of these drugs has decreased by 20% to 50% and the emergence of strains resistant to these drugs is one of the main problems of treatment. Therefore, the discovery of new anti-leishmanial drugs and treatment strategies is needed Antimicrobial Peptides (AMP) are an important component of the innate immune system and resilience of humans and animals, which have been identified in various sources such as bacteria, plants, insects and mammals [6-8]. The effects of different peptides including scropin A and melittin (based on insects) have been evaluated against L. donovani. In addition, the effect of peptides such as histidine-5, and skin polypeptide YY (of mammalian origin) has been reported in comparison with L. donovani and L. major [9,10]. Considering the strong antimicrobial activity of AMPs, in this study, the antimicrobial activity of Leishmania in vitro of a short cationic peptide (CM11) was investigated against the amastigote forms of L. major. This peptide is an amphipathic hybrid peptide derived from 2 residues-8 residues of cropin A and 6 residues-9 residues of melatonin consisting of a very basic N-term domain of cropin A and a relatively hydrophobic C-terminal domain of malatin [11,12].

Material and Methods

Peptide Synthesis CM11 peptide was synthesized by solid phase synthesis using standard protocols. 21 peptides were immobilized on C18 by semipreparative high-performance liquid chromatography. The purity of the synthesized peptide was more than 95%.

Culture of Leishmania major. Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Promastigotes were cultured in RPMI 1640 Glutamax medium (Gibco, San Francisco, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 100 mg ml-1 streptomycin and 100 IU ml-1 penicillin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, USA) at 25.00°C ± 1.00°C. A stable growth factor from promastigote culture was used to infect RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Macrophage cell culture

Macrophage cell RAW264.7 macrophages (ATCC number TIB-71) were obtained from Iran Biological Resources Center, Tehran. Adherent macrophages were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10.00% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5.00% CO2 . Macrophages were collected with a reduction of approximately 80.00% [13-17].

Determination of the effective concentration of glucantim against L. major amastigote. Glucantim ® (Rorer Rhone-Poulenc Specia, Paris, France) was received from the Faculty of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran. RAW264.7 macrophage cells (2×104 cells per cycle) were cultured in RPMI medium containing 10.00% FBS in 8-well slides (SPL Life Sciences Co., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and incubated at 37°C with 5.00% CO2 for 6 hours, then macrophages dependent on stationary phase promastigotes of L. major were incubated at a ratio of 10 per infected macrophage at 37°C for 18 hours. After 18 hours of incubation, each kilo was washed three times with cutting RPMI to isolate parasites caused by contraction. Then they were treated for 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours with different concentrations (30.87 μM, 61.75 μM, 123.50 μM and 247.00 μM) with Glucantim ® solution. No drugs were added to the control wells. Finally, the chamber slides were fixed in absolute methanol and stained with Giemsa 10.00%. The percentage of infected macrophages was evaluated by counting the number of amastigotes per infected macrophage by examining 100 macrophages compared to control wells. Effect of CM11 peptide on L. major amastigote with DAPI staining. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells (2×104 cells per layer) were seeded in 8-well chamber slides and incubated at 37°C with 5.00% CO2 for 6 hours. Then, hair major macrophages were usually infected with a ratio of 10:1 (parasite: macrophage) and incubated for 18 hours at 37°C, and then after 18 hours of incubation, washing was done three times with RPMI medium. CM11 peptide solutions were used in contrast [18-22].

Results

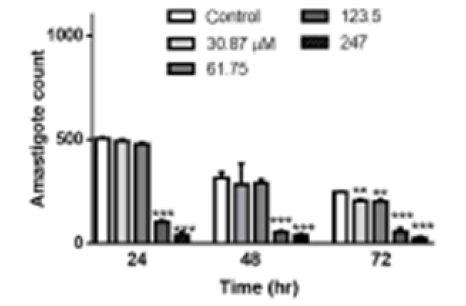

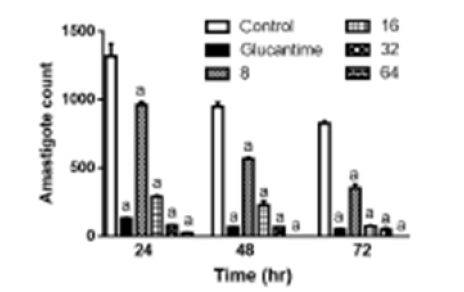

Determining the effective concentration of Glucantim ® against L. major amastigote. To find the most suitable concentration of Glucantim® with the highest effect and the lowest cytotoxicity, different concentrations of this drug were prepared and prepared at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours after exposure to the in vitro test. There was no statistically significant difference between the concentrations of 30.8775 μM mL-1 and 61.75 μM mL-1 compared to the negative control after 24 hours and 48 hours, but after 72 hours, these Glucantim® concentrations showed a statistically significant difference (p 0.05<). The results showed that 123.50 μM ml glucantim was the best time to inhibit the growth of L. amastigote (Figure 1). Antiamastigote effect of CM11 peptide. The effect of different concentrations of CM11 peptide against L. major amastigotes was investigated by DAPI staining. All concentrations of CM11 peptide and Glucantim ® as a positive control statistically significantly reduced the number of amastigotes per infected macrophage compared to the negative control (Figure 2). The IC50 of the CM11 peptide was against amastigote forms for 48 hours. After 48 hours’ Statistical analysis showed that the anti-Leishmania activity was dose-dependent of the CM11 peptide.

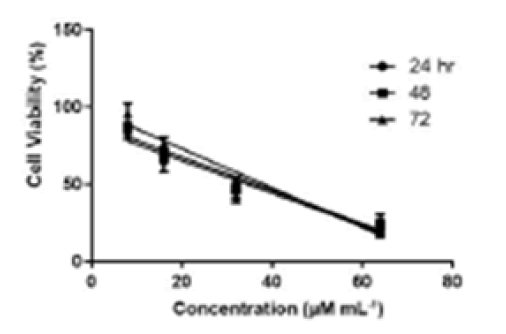

Cytotoxic effect of CM11 on rat fibroblasts. The results of the MTT test at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours are shown in Figure 3 A concentration of 8 μM CM11 peptide showed no toxicity at all-time points, while fibroblast lifespan was decreased at 16 μM, 32 μM, and 64 μM. Also, Glucantime® showed a higher toxic effect than the negative control group. The results showed that CM11 reduces the stability of fibroblasts with an IC50 value of 36.57 μM after 48 hours.

Figure 3: CCytotoxic activity of CM11 peptide on fibroblast cells after MTT test at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours. Inhibitory concentration at 50.00% (IC50) was checked using GraphPad Prism. MTT: 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

Discussion

According to the reports of the World Health Organization, leishmaniasis is one of the most important parasitic diseases, and its treatment is a research priority [23,24]. Leishmaniasis is still one of the health threats in Iran, so controlling this disease is very important. Therefore, the vaccine for this disease has been found and the challenges to develop an effective vaccine are still ongoing [25,26]. In this regard, the removal of reservoirs and drug treatment are the most important methods of disease control and prevention. Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and the antibiotic Meglumine (Glucantime®) have been used to treat leishmaniasis for years and are still the first-line drugs. However, in recent years, drug-resistant Leishmania has appeared in endemic areas such as Iran [15,27]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate a new group of anti-Leishmania compounds. Based on this, various types of anti-leishmania agents such as plant extracts, nanomaterials, and antimicrobial peptides have been investigated recently.

One of the most attractive anti-leishmania agents is AMP, which has recently been evaluated for therapeutic strategies [28]. It should be noted that secondary infection by bacteria or fungi is one of the main problems in the treatment of leishmaniasis. Due to the antibacterial and antifungal effects of AMPs, the use of these peptides can also be effective in removing bacterial and fungal contamination from waste. However, the size of natural AMPs and some side effects such as toxicity in eukaryotic cells at high doses are major problems. To overcome these problems, hybrid and short peptide analogs with more antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity have been designed [29-31]. One of these peptides is CM11, a short amphipathic cationic peptide with antimicrobial effects against a wide range of pathogenic bacteria [32,33]. Based on this, in the present study, the effect of CM11 peptide against the Leishmania amastigote type was investigated. For this purpose, we first determined the dose of glutamine as a positive control through an in vitro test. Based on the results, 123.50 μM mL-1 of Glucantim® was the most suitable concentration that inhibited the growth of L. major amastigote forms in the culture medium. In addition, DAPI staining microscopy and immunofluorescence showed the concentration of 8 μM CM11 peptide after 24 hours without toxic effect on fibroblast cells. However, the IC50 value of the peptide after 48 hours was 9.58 μM (13.50 μg/mL).

It should be noted that all concentrations of CM11 peptide and Glucantime® (123.50 μM mL-1) lead to a decrease in the number of amastigote forms per infected macrophage compared to the negative control. Our findings showed that the CM11 peptide is effective against L. major due to metabolism. Recently, several studies have been conducted to evaluate the antiparasitic activity of different peptides against Leishmania species. It should be noted that these studies show promastigote sensitivity to AMP more than amastigotes; This can be attributed to the morphology of the life cycle and biochemical differences of the two stages of the Leishmania prostate parasite and their location in the macrophage phagolysosome [20,34]. Although many studies have shown the anti-Leishmania activity of peptides or other compounds, evaluation methods have been different. Therefore, their performance is unlikely to be properly compared. However, an attempt has been made to address some of these studies.

A study has proposed Nitroimidazolyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole as an antiparasitic agent with an IC50 value of 9.35 mm ± 9.67 mm against promastigote forms of L. major without cytotoxicity in host cells. However, compared to the CM11 peptide, the effective concentration of this compound is much higher [35].

Another study has shown that different concentrations of nanosilver can reduce the large production of large amastigotes. However, different concentrations of nanosilver significantly reduced lesions and the number of amastigotes in Balb/c mice [22]. It has previously been shown that treatment with 0.10% nanosilver for two weeks has therapeutic potential in L. major (MRHO/IR /75/ER) in infected Balb/c mice, but compared to AMP such as peptide CM11, this compound is highly toxic [28].

In general, the nature of antimicrobial peptides varies so each peptide can have different functions and effects such as antimicrobial activity or toxicity. According to many studies, these effects are dependent on hydrophobicity, amphiphilicity, charge, stretchability, the tendency of the peptide to form a barrel, types of target cells, and amino acid properties. On the other hand, the sensitivity to AMPs and the difference in the viability of eukaryotic cells is also dependent on membrane lipid composition, cell membrane hydrophobicity and cell metabolic activities [12,32,36] Therefore, it should be noted that the parasitic type of Leishmania will also be effective in the anti-Leishmania effect of the CM11 peptide due to the composition and structure of the cell membrane.

Regarding the use of anti-leishmania drugs on the skin, the toxic effects of the peptide on mouse fibroblasts were investigated. The MTT results showed that the CM11 peptide, after 48 hours of incubation, reduced the IC50 value to 36.50 μM (51.60 μg/ml), which is much higher than the anti-Leishmania peptide concentration. In the study of Moghadam et al., it has been shown that the CM11 peptide can lead to the death of 50.00% of some eukaryotic cells at a dose of 12.00 μM (16.00 μg mL-1) after 48 hours, while the survival of macrophages is about 70.00 33%. Some differences in the findings can be influenced by the type of target pathogen (bacteria or parasite) or host cells, the research method and the presence of stimulators and inhibitors [37].

Also, a similar study has investigated the cytotoxic effect of BP100 peptide (an analog of CM11 peptide). Based on the results, this peptide had a cytotoxic effect in the concentration range of 51.00 μM to 63.00 μM, but its evaluation in the mouse model showed that the peptide is non-polar for mice up to a dose of 1000 mg to 2000 mg per kilogram of body weight [30].

Conclusion

By comparing the studies done in this field and the current study, it can be concluded that the CM11 peptide has the potential to treat infections without harming living cells, however, further studies on animal models are needed. This research was the first step in determining the anti-leishmania effect of CM11 peptide as a new drug candidate. The results showed that the CM11 peptide has significant anti-leishmania activity in laboratory conditions compared to the negative control group. Also, between the IC50 value of CM11 peptide for amastigote forms (28.58 µM) and fibroblast cells (57.36 µM) after 48 hours was affected, and the low cytotoxic effect of the peptide was observed in the concentration of bacterial anti-amastigote in the experiment.

References

- Brito ME, Andrade MS, Dantas-Torres F, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeastern Brazil: a critical appraisal of studies conducted in State of Pernambuco. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012; 45:425-9.

- Trajer AJ, Sebestyén V. The changing distribution of Leishmania infantum Nicolle, 1908 and its Mediterranean sandfly vectors in the last 140 kys. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):1-5.

- Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PloS one. 2012;7(5): e35671.

- Mohebali M, Javadian E, Yaghoobi Ershadi MR, et al. Characterization of Leishmania infection in rodents from endemic areas of the Islamic Republic of Iran. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal.2004;10 (4-5):591-599.

- Shirzadi MR, Esfahania SB, Mohebalia M, et al. Epidemiological status of leishmaniasis in the Islamic Republic of Iran. EMHJ. 1995;21(10): 736-742.

- Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005;3(10):777-88.

- Thevissen K, Kristensen HH, Thomma BP, et al. Therapeutic potential of antifungal plant and insect defensins. Drug discovery today. 2007;12(21-22):966-71.

- Slocinska M, Marciniak P, Rosinski G. Insects antiviral and anticancer peptides: new leads for the future?. Protein and peptide letters. 2008;15(6):578-85.

- Luque‐Ortega JR, van't Hof W, Veerman EC, et al. Human antimicrobial peptide histatin 5 is a cell‐penetrating peptide targeting mitochondrial ATP synthesis in Leishmania. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22(6):1817-28.

- Vouldoukis I, Shai Y, Nicolas P, et al. Broad spectrum antibiotic activity of skin-PYY. Febs Letters. 1996 ;380(3):237-40.

- Ferre R, Badosa E, Feliu L, et al. Inhibition of plant-pathogenic bacteria by short synthetic cecropin A-melittin hybrid peptides. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006 ;72(5):3302-8.

- Azad ZM, Moravej H, Fasihi-Ramandi M, et al. In vitro synergistic effects of a short cationic peptide and clinically used antibiotics against drug-resistant isolates of Brucella melitensis. Journal of medical microbiology. 2017;66(7):919-26.

- Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, et al. Advances in leishmaniasis. The Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1561-77

[Google Scholar] [Cross Ref].

- Mohebali M, Fotouhi A, Hooshmand B, et al. Comparison of miltefosine and meglumine antimoniate for the treatment of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) by a randomized clinical trial in Iran. Acta tropica. 2007;103(1):33-40.

- Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to Glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(5): e162.

- Mittal MK, Rai S, Gupta S, et al. Characterization of natural antimony resistance in Leishmania donovani isolates. Am . trop med hyg. 2007;76(4):681-8.

- Zarean M, Maraghi S, Hajjaran H, et al. Comparison of proteome profiling of two sensitive and resistant field Iranian isolates of Leishmania major to Glucantime® by 2-dimensional electrophoresis. Iranian journal of parasitology. 2015;10(1):19.

- Hancock RE, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24(12):1551-7.

[Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Zhang L, Falla TJ. Host defense peptides for use as potential therapeutics. Curr opin investing drugs. 2009 ;10(2):164-71.

- Diaz-Achirica P, Ubach J, Guinea A, et al. The plasma membrane of Leishmania donovani promastigotes is the main target for CA (1–8) M (1–18), a synthetic cecropin A–melittin hybrid peptide. Biochemical journal. 1998;330(1):453-60.

- Badosa E, Ferre R, Planas M, et al. A library of linear undecapeptides with bactericidal activity against phytopathogenic bacteria. Peptides. 2007;28(12):2276-85.

- Mohebali M, Rezayat MM, Gilani K, et al. Nanosilver in the treatment of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER): an in vitro and in vivo study. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015;17(4):285-9.

- Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases. 2004;27(5):305-18.

- Ouellette M, Papadopoulou B. Mechanisms of drug resistance in Leishmania. Parasitology Today. 1993;9(5):150-3.

- Handman E, Noormohammadi AH, Curtis JM, et al. Therapy of murine cutaneous leishmaniasis by DNA vaccination. Vaccine. 2000;18(26):3011-7.

- Stober CB, Lange UG, Roberts MT, et al. From genome to vaccines for leishmaniasis: screening 100 novel vaccine candidates against murine Leishmania major infection. Vaccine. 2006 ;24(14):2602-16.

- Singh N, Kumar M, Singh RK. Leishmaniasis: current status of available drugs and new potential drug targets. Asian Pac j trop med. 2012;5(6):485-97.

- Ghaffarifar F. Leishmania major: in vitro and in vivo anti-leishmanial effect of cantharidin. Experimental Parasitology. 2010 ;126(2):126-9.

- Montesinos E. Antimicrobial peptides and plant disease control. FEMS microbiology letters. 2007;270(1):1-1.

- Acott TS, Hoskins DD. Bovine sperm forward motility protein. Partial purification and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1978 ;253(19):6744-50.

- Moura PP, Franco MM, Silva TA, et al. Caracterizacao de proteinas do plasma seminal e sua relaçao com parametros de qualidade do sêmen criopreservado em ovinos. Ciencia Rural. 2010; 40:1154-9.

- Villemure M, Lazure C, Manjunath P. Isolation and characterization of gelatin-binding proteins from goat seminal plasma. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1(1):1.

- Moghaddam MM, Aghamollaei H, Kooshki H, et al. The development of antimicrobial peptides as an approach to prevention of antibiotic resistance. Rev Med Microbiol. 2015;26(3):98-110.

- Marr AK, Gooderham WJ, Hancock RE. Antibacterial peptides for therapeutic use: obstacles and realistic outlook. Curr opin pharmacol. 2006;6(5):468-72.

- Poorrajab F, Ardestani SK, Emami S, et al. Nitroimidazolyl-1, 3, 4-thiadiazole-based anti-leishmanial agents: Synthesis and in vitro biological evaluation. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44(4):1758-62.

- Rudenko SV, Wajdi KJ. Modulatory effect of peptide structure and equilibration conditions of cells on peptide-induced hemolysis. Bulletin of Kharkiv National University named after VN Karazin. Series: Biology. 2005 :139-46.

- Dolis D, Moreau C, Zachowski A, et al. Aminophospholipid translocase and proteins involved in transmembrane phospholipid traffic. Biophysical chemistry. 1997;68(1-3):221-31.