Methods for birth control in Humans

Received: 08-Aug-2020 Accepted Date: Aug 20, 2020; Published: 31-Aug-2020

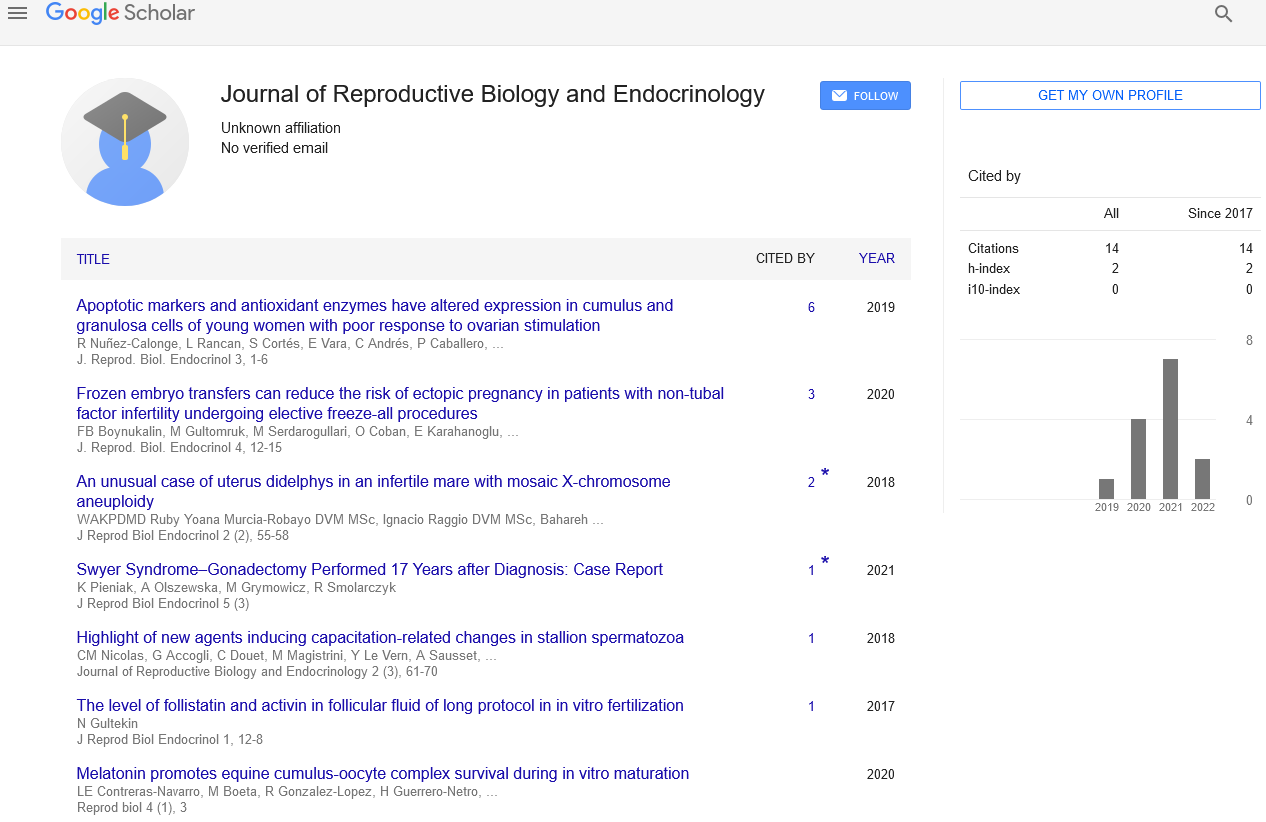

Citation: Ilan O. Methods for birth control in Humans. J Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020; 4(3):4.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Introduction

Contraceptive method helps to prevent unwanted pregnancies. These methods have recognized that limited uptake of these latter methods will result unless

are grouped into the allowing categories

Periodic abstinence:

Couple avoid or abstain from coitus from day 10 to 17 of the menstrual cycle.

Withdrawal or coitus interrupts:

Male partner withdraws his penis from the vagina just before ejaculation to avoid insemination.

Lactational amenorrhea or (Absence of menstruation): Menstrual cycle does not oocur during the period of intense lactation following child birth. Lactational amenorrhea has been reported to be effective only upto a maximum period of six months following parturition. Side effects are almost nil in these methods as no medicine or devices are used.

Physical meeting of ovum and sperm is prevented with the help of barriers

Condom

Used to cover the penis in the male or vagina and cervix in the female

Reusable barrier

They include diaphragms, cervical cup and vaults. These are inserted into the female reproductive tract to cover the cervix during intercourse.

Intra uterine devices

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are small devices placed in uterus to disturb the process of insemination. They are very popular around the world and one of the most effective forms of birth control. A severely understudied aspect of contraceptives is their sexual acceptability, or how methods influence the user’s sexual experiences, which can in turn influence family planning preferences and practices. Though contraception is expressly designed for sexual activity, we know little about how contraceptives affect women’s sexual functioning and well-being. This “pleasure deficit” is even more striking when compared to research on male-based methods or even newer multiprevention technologies for women, such as microbicides Researchers and policymakers have recognized that limited uptake of these latter methods will result unless they are sexually acceptable for both partners. In comparison, portrayals of female-based contraceptives in the scientific, media, and public policy spheres are almost entirely de-eroticized. Researchers have documented a number of reasons why we consider contraceptives more a medical than a sexual good. For example, advocates from the late 19th through the end of the 20th century sought medical and legal respectability for birth control, thus downplaying its potentially sexually revolutionary aspects—especially for women. Even today, while advertisements for male condoms and erectile dysfunction medications highlight sexual pleasure and enjoyment as the products’ main selling points, few erotic scripts of contraceptives used by women exist in mainstream culture, illustrated in both contraceptive advertisements and pornographic films. The state can also devalue women’s sexuality in place of narratives around motherhood—as evidenced, for example, in laws surrounding health care reform and over-the-counter access to emergency contraception .1 School-based sexuality educations similarly focuses on the harms versus the pleasures of sex, especially for girls and young women. Clinically, care providers may lack both

tools and time to discuss sexual issues with patients, and providers may be especially unlikely to inquire about sexuality in relationship to new contraceptive methods. Public health programs and policies can also both reflect and perpetuate dominant gendered assumptions about women’s sexuality—for example, with female condom programs focusing on reproductive health outcomes versus sexual rights or with adolescent pregnancy prevention policies that emphasize “sex is not for fun” and that young women should be

sexually uninterested. All these phenomena underscore the notion that contraception is a medical versus a sexual good; they also contribute to mixed messages about whether contraceptives should be sexually acceptable at all for women.