Agatha Clemens*

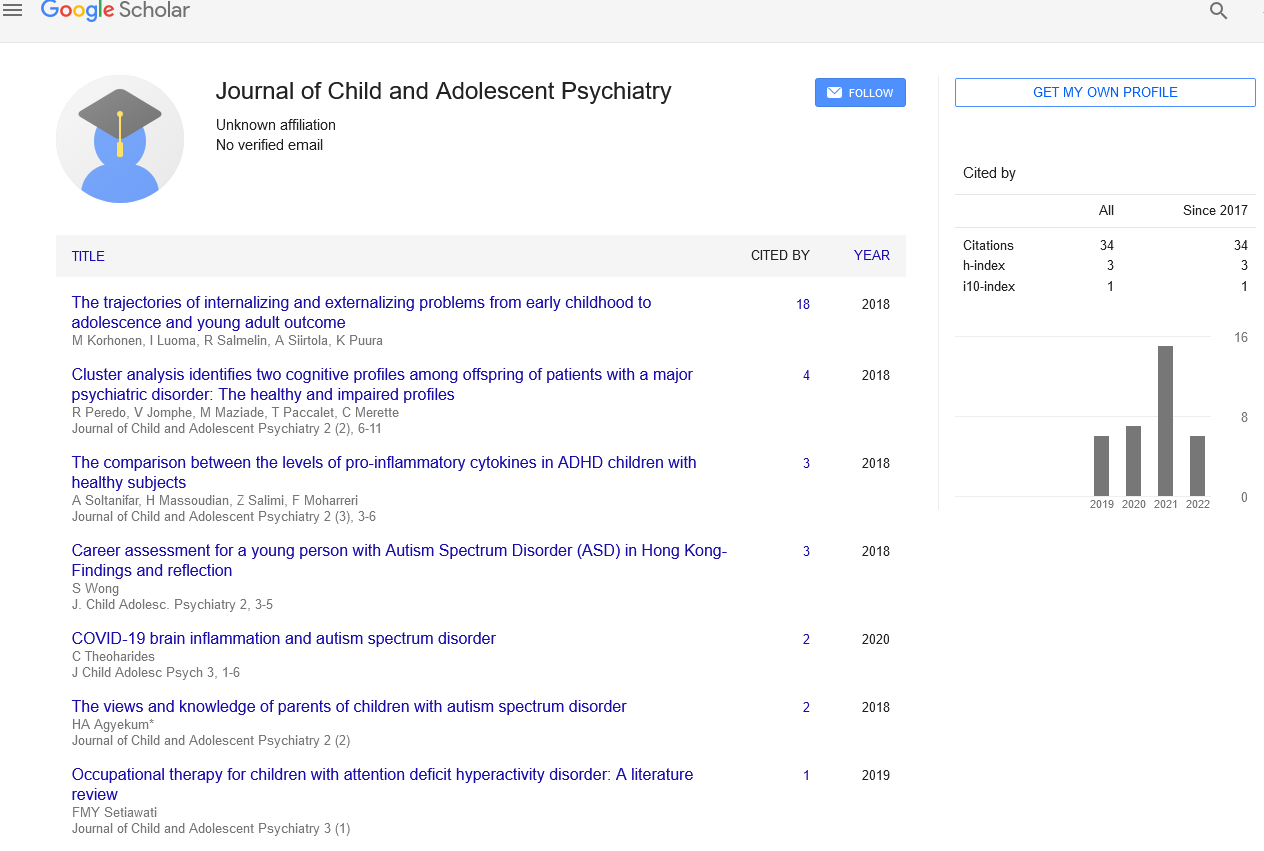

Editorial office, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, UK, Email: childpsy@psychiatryres.com

*Correspondence:

Agatha Clemens,

Editorial office, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,

UK,

Email: childpsy@psychiatryres.com

Received: 04-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5938;

Editor assigned: 12-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. PULJCAP-22-5938(PQ);

Accepted Date: Nov 29, 2022;

Reviewed: 16-Nov-2022 QC No. PULJCAP-22-5938(Q);

Revised: 27-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. PULJCAP-22-5938(R);

Published:

30-Nov-2022, DOI: 10.37532/puljcap.2022.6(6);01-02

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

In Japan, playing video games is the most popular form of recreation, particularly among boys. Over time, playing video games online has become more prevalent among kids in school. As a result, young children in Japan are now experiencing a serious societal issue due to their excessive online gaming. Previous research has shown that children and teenagers who play too much internet gaming may experience a range of mental health problems. There are more children and adolescents seeking treatment at medical facilities offering child and adolescent psychiatry treatments for a variety of issues associated to excessive gaming. The purpose of this study was to look into how gaming disorder (GD) is being treated in therapeutic settings in Japan.

Keyword

Functional motion disorders,Taijin kyofushoIntroduction

The most popular pastime for kids and teenagers in Japan,particularly among boys,

is playing video games. 85.0% of respon--dents to a national study (n=5,096)

admitted to playing games at

least once in the previous 12 months, with 92.6% of men and

77.4% of women. Nearly half of all respondents (48.1%) said they

play games primarily online. In recent years, younger people are

starting to use the Internet. 33.7% of children aged 10 and younger,

62.6% of children aged 2, and 82.3% of children aged 6 accessed the

Internet for any reason, according to a large-scale poll of parents of

children under 10 (n=2,294). The same survey's findings revealed that

82.0% of kids (n=5,805) under the age of 17 played games online.

72.4 % of primary school kids (n=1,101) have access to the Internet

through video game consoles. Nakayama et al. cautioned that their

survey's findings (n=549) showed that the risk for problematic gaming

was positively correlated with the younger the age at which weekly

gaming began, despite the fact that playing online games has become

increasingly prevalent among school-aged children over time. When

considered as a whole, excessive online gaming by young children in

Japan has developed into a serious social issue.

Additionally, because gaming disorder (GD) was added to the

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision as a

psychiatric disease, An abundance of online gaming has been

linked to neurodevelopmental issues like autism spectrum

disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

according to earlier research (ADHD). According to Ostinelli et

alsystematic .'s review and meta-analysis, about one-third of those with

GD also reported depression. Teenage problematic gaming was linked

to despair and anxiety, according to a large-scale cohort study in

Sweden. According to certain brain imaging studies, GD and

depression may have a similar aetiology .Japan has also observed

physical and psychological problems following teens' excessive gaming.

Regarding neurodevelopmental diseases, a comprehensive evaluation

of 1,028 previously published publications revealed that GD

symptoms and ADHD symptoms were consistently linked.

The rise in cases of school refusal and absenteeism, many of which

appear to increase during adolescence and frequently progress to the

stage known as "hikikomori," a condition characterised by severe

social withdrawal, has caused long-standing and unresolved issues for

mental health professions in Japan. Hikikomori was initially thought

to be a sickness that was connected to Japanese culture (28). Shame

and amaze, which refer to the acceptability of excessively dependent

behaviours, have historically characterized the culture backdrop of

Japan. Taijin kyofusho, a severe kind of social anxiety, may be caused

by this equally culturally tied disease. However, as more and more

publications on hikikomori are published in English, there have been

progressively more cases of hikikomori recorded outside of Japan.

There have been reports of psychological variables related to the

genesis of hikikomori outside of Japan, including shyness,

avoidance tendencies, introversion, and loneliness. These

psychological elements are all very closely tied to Internet addiction.The Internet makes it possible for people who exhibit these

psychological traits to locate a place that is both normative and

comfortable, which in turn motivates them to stay there. A

possible connection between hikikomori and GD has been

raised by recent investigations. It is not surprising that there is a

major association between hikikomori and

GD where regulations are lax and cultural as well as individual, given

how many kids and teenagers utilise the Internet to play online games

with both society and parental support.