Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease A Child is Not a Young Adult

Received: 11-Dec-2017 Accepted Date: Dec 22, 2017; Published: 29-Dec-2017

Citation: Nayak A, Khare J. Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease–A Child is not a Young Adult.J Pediatr Health Care Med 2017;1(1):16-19.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing cause of concern “over a” worldwide and is associated with significant mortality and morbidity, both, in adults and children. Pediatric CKD should be considered differently from adult CKD as they differ with respect to epidemiology, etiology, evaluation and management. In 2012, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) defined CKD however, this definition may not be applicable for children under 2 years of age, as their nephrons are yet to mature. Also, an infant born with a congenital renal anomaly may be diagnosed as CKD very early. Common complications of CKD like anemia, hypertension and cardiovascular disease are similar in pediatric CKD like their adult counterparts. However, there are certain complications which are special among pediatric patients like growth retardation and neurocognitive impairments. This review describes the various aspects of pediatric CKD highlighting complications unique to pediatric CKD.

Keywords

Pediatric; Chronic kidney disease; KDIGO; Growth retardation; Neurocognitive impairments

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing cause of concern over a worldwide scale affecting populations of high, middle and low income countries. It is associated with significant mortality and morbidity, both, in adults as well as children. It is essential to consider pediatric CKD apart from adult CKD as they differ with respect to epidemiology, etiology, evaluation and management. The special issues in pediatric CKD need to be understood and evaluated in order to provide them with the best therapy. This review describes the various aspects of pediatric CKD highlighting complications unique to pediatric CKD.

Diagnosis of CKD

Until 2012, the diagnosis of CKD varied from continent to continent due to varying definitions used. In 2012, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) defined CKD as a structural or functional abnormality of kidneys lasting more than 3 months duration [1]. However, this definition is not applicable for children under 2 years of age, whose nephrons are yet to mature. Also, an infant born with a congenital renal anomaly may be diagnosed as CKD before attaining 3 months of age.

The traditional Schwartz formula [2] has been used for bedside estimation of glomerular filtration rate in children. It was used for decades due to the ease of bedside calculation and validation done in 1970s.

GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2, Body Surface Area)= 0.55 × Length (cm)/Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)2

However, recently it was observed that it tended to overestimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as compared to recent gold standard of GFR estimation using iohexol. It was inferred that this was due to the more accurate enzymatic method of estimation of creatinine compared to the old Jaffe’s chromogen method. A newer formula, dubbed the modified Schwartz formula [3], was arrived at, which employed a lower constant.

eGFR=0.413 × Height (cm)/Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)3

Epidemiology.

There has been a significant rise in the prevalence of pediatric CKD worldwide over the past few years [4]. This may be due to early detection of cases during childhood and longer survival of patients due to widespread availability of dialysis and transplantation. The prevalence of children diagnosed of end stage renal disease (ESRD) ranges from 65 to 85 per million age related population (pmarp) based on registries of western countries [5]. Until 2008, the incidence of children less than 20 years of age receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT) was about 9 pmarp worldwide [3] while it was 15.5 pmarp in the USA [6]. Adolescents receiving RRT outnumber the children based on registries [6]. The incidence and prevalence in India, similar to other developing countries, is unknown so far due to lack of pediatric CKD registry.

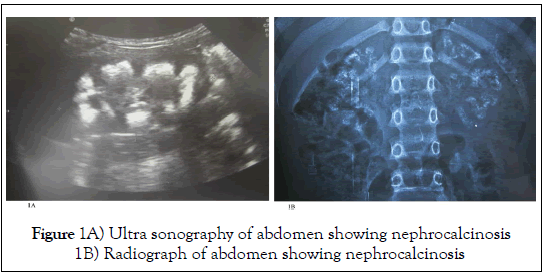

The etiology of CKD varies not only among pediatric and adult patients, but also within the pediatric group. Congenital Anomaly of Kidney and Urinary Tract (CAKUT) is the most common cause in children followed by chronic glomerulonephritis and inherited nephropathies [7,8]. Among adolescents, chronic glomerulonephritis predominates. Few causes of CKD may present as medullary nephrocalcinosis like renal tubular acidosis, hyperparathyroidism, alprot syndrome, infections and many other (Figure 1) [9]. However, evaluation of the urinary tract is extremely essential among all pediatric cases to assess reversibility, to reduce incidence of infections and prior to transplantation. Recent data shows that obese children [10], premature, low birth weight, and small for gestational age [11] babies are prone to CKD in their adolescence.

Registry data also reflects a racial and gender based diversity in the etiology and prognosis. African Americans in North America and native aborigines in Australia have increased incidence of CKD and faster progression to ESRD as compared to their Caucasian counterparts [5]. Males are more common than females, probably because CAKUT is more common in males [5].

Complications of CKD

Children and adolescents share common complications of CKD like anemia, hypertension and cardiovascular disease with their adult counterparts. However, there are certain complications which are special among pediatric patients. Growth retardation and maldevelopment of neurocognitive skills are chief among them.

1) Growth and development

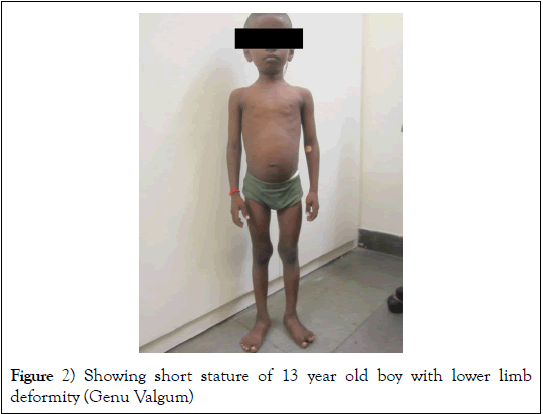

Short stature is defined as height two standard deviation scores below that for the same age and sex [12]. However, it is necessary to use growth charts appropriate for the respective race as well. North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) registry data has revealed that about one-third of pediatric patients have short stature [13]. Even after advancement in the therapy of CKD about 30 to 60% of patients have short stature (Figure 2) [14]. Their height is usually less than third percentile for the age and this is attributed to multiple factors like uremic anorexia induced under-nutrition, increased protein catabolism, water and electrolyte abnormalities, hormone imbalance and resistance, persistent metabolic acidosis, mineral bone disease, anemia and use of corticosteroids for nephritic syndrome and for transplantation [15-17]. Under-nutrition predominates as the etiology for short stature during infancy and childhood as growth during this period is dependent on the calorie and protein intake [15]. Growth hormone resistance occurs due to chronic inflammation and acidosis [18,19]. Imbalance in normal sex hormone production occurs in CKD. Latter two factors are primarily responsible for the lack of pubertal growth spurt in CKD and improper development of secondary sexual characters among adolescents. It has been observed that children transplanted before puberty, or those who are administered growth hormone regularly may achieve catch up growth [20,21].

2) Neurocognitive skills impairment and quality of life

Long term follow up of children diagnosed with CKD exhibit certain psychosocial issues due to multiple factors [22]. Lack of independence, dependence on dialysis, multiple medications, poor quality of life, short stature and excessive parental indulgence compared to their healthy peers leads to a sense of inferiority complex, alienation and depression among these children [23]. Cognitive skills also have been seen to be impaired among patients who reach adulthood. Overall, children with CKD have been observed to have lower health related quality of life scores [24] (HRQoL).

3) Anemia

Anemia is commonly observed among patients with CKD. A criterion for diagnosis of anemia in children with CKD has been given in Table 1 as described in KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease Kidney International [25].

| AGE (Years) | Hemoglobin Concentration (G/dL) |

|---|---|

| 0.5 to 5 | Less than 11 |

| 6 to 12 | Less than 11.5 |

| 13 to 15 | Less than 12 |

| More than 15 | Males – less than 13 |

| Females – Less than 12 |

TABLE 1 Diagnostic criteria for anemia in children (25)

Registry data reveals that the prevalence of anemia ranges from 73% to 93% over worsening grades of pediatric CKD [26]. Decreased erythrocyte survival, hemolysis, erythropoietin deficiency and blood loss from gut and during dialysis are among the predominant causes of anemia [27,28]. A steady decrease of 0.3 g/dL for every 5 ml/min decrease in eGFR has been observed [29]. Anemia is attributed to impairment of neurocognitive skills [30], poor quality of life [31], increased fatigue, generalized weakness, and cardiomyopathy [32] among these patients.

4) Hypertension

Cardiovascular complications have been found to be the most common cause of mortality in pediatric CKD [33,34] similar to adult CKD. Hypertension, a traditional reversible risk factor for cardiovascular disease, has been frequently observed among CKD patients. Among these, patients with glomerular diseases had a higher incidence and required multiple antihypertensive drugs as compared to those with other etiologies. The CKiD cohort study [35] has revealed that 54% of patients had uncontrolled hypertension and 48% of patients had uncontrolled blood pressure levels in spite of antihypertensive drugs. In addition, 38% had masked hypertension, unmasked during 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring [35].

5) Cardiovascular Disease

As mentioned earlier, cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of mortality among pediatric CKD, arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy being the most common [36]. Uncontrolled hypertension, anemia, fluid overload, left ventricular hypertrophy, vascular calcification, hyperparathyroidism and chronic inflammation are major factors among them [37]. It is therefore important to control these risk factors before they may result in advanced cardiac disease.

Management of Pediatric CKD

Management of pediatric CKD involves screening for renal disease, early detection, and retardation of progression of early stages of CKD and finally, RRT for those with ESRD. Screening of school children for renal disease has been a part of health programs of many countries [5]. Early intervention has been found to halt or retard the progression of CKD. Medical therapy is warranted for control of hypertension, management of anemia and alleviation of acidosis.

1) Retardation of progression of CKD

Progression of CKD to ESRD has been found to be influenced by several factors. Glomerular diseases progress faster than CAKUT [38]. In this study, uncontrolled hypertension, anemia, heavy proteinuria and male gender were found to be associated with faster progression. Often it remains partially treated or not treated at all. Use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) has been shown to not only reduce blood pressure and proteinuria, but also retard the progression of CKD [39]. Hence they are considered the first line of treatment of hypertension and proteinuria. The ESCAPE trial revealed that intensive control of BP as opposed to conventional control was effective in retarding decline of GFR [40].

2. Anemia

Alleviation of anemia is associated with decreased fatigue, reduced cardiovascular risk and better quality of life. However, correction above 13 g/dL has been associated with increased adverse outcomes. Hence among children, a hemoglobin target of 11-12 g/dL is recommended with iron and Erythropoietin Stimulating agent (ESA) supplementation. Iron status needs to be corrected prior to administration of ESA [25]. If transferrin saturation level less than 20% and serum ferritin concentration less than 100 ng/ml then oral or parenteral iron therapy is recommended [25].

3. Growth and development

Studies have shown that providing 80% of recommended nutrition is associated with prevention of short stature in infancy and childhood [18]. Administration of recombinant human growth hormone over two years is usually associated with catch-up growth [41]. Alleviation of metabolic acidosis with sodium bicarbonate or dialysis, correction of mineral bone disease, steroid free regimen during transplantation and correction of anemia are other interventions advised for achieving growth in CKD.

4. Renal replacement therapy

Dialysis among pediatric CKD patients’ needs special consideration as compared to adults, though the modalities are the same. Though peritoneal dialysis was widely prescribed earlier, hemodialysis has surpassed it lately [15]. Though pre-emptive transplantation is recommended, dialysis needs to be performed as a bridging therapy in certain situations. Hemodialysis is associated with frequent visits to the dialysis centres leading to frequent disruption of educational activities. Dependence on dialysis machine, frequent venepuncture of fistulae, scars over arms, and restriction of travel lead to poor quality of life as compared to peritoneal dialysis and renal transplantation. Peritoneal dialysis is associated with more independence, lesser disruption of educational activities and better quality of life. Renal transplantation is associated with better control of hypertension, alleviation of anemia and better quality of life. However, correction of lower urinary tract abnormalities in children with CAKUT is essential prior to transplantation to avoid renal allograft injury. Also lack of adherence to medication has been found to be an important cause of graft loss in adolescents.

Conclusion

Pediatric CKD is different from adult CKD with respect to etiology, presentation and outcomes. Complications like growth retardation and neurocognitive impairment are special issues in such patients. Proper nutrition and growth hormone administration is an essential part of management in addition to other measures. Registry data is needed for estimation of the pediatric CKD incidence and prevalence among developing countries.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Grant Support

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

REFERENCES

- Are C, Chowdhury S, Ahmad H, et al. Predictive global trends in kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013;3:1–150.

- Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, et al. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 1976;58:259–263.

- Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20:629-637.

- Baum M. Overview of chronic kidney disease in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010;22:158–160.

- Harambat J, Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, et al. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2012;27:363–373.

- US Renal Data System, USRDS (2010) Annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

- Ardissino G, Daccò V, Testa S, et al. ItalKid project epidemiology of chronic renal failure in children: Data from the ItalKid project. Pediatrics 2003;111:382–387.

- Fivush BA, Jabs K, Neu AM, et al. Chronic renal insufficiency in children and adolescents: the 1996 annual report of NAPRTCS. Pediatr Nephrol 1989;12:328–337.

- Habbig S, Beck BB, Hoppe B. Nephrocalcinosis and urolithiasis in children. Kidney Int 2011;80:1278-1291.

- Ding W, Cheung WW, Mak RH. Impact of obesity on kidney function and blood pressure in children. World J Nephrol 2015;4: 223–229.

- Carmody JB, Charlton JR. Short-term gestation, long-term risk: prematurity and chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics 2013;131:1168– 1179.

- Oostdijk W, Grote FK, deMuinck Keizer-Schrama SM, et al. Diagnostic approach in children with short stature. Hormone Res 2009;72:206–217.

- Seikaly MG, Salhab N, Gipson D, et al. Stature in children with chronic kidney disease: Analysis of NAPRTCS database. Pediatr Nephrol 2006;21:793–799.

- Mehls O, Lindberg A, Nissel R, et al. Predicting the response to growth hormone treatment in short children with chronic kidney disease. J Clinical Endocri Metabolism 2010;95:686–692.

- Becherucci F, Roperto RM, Materassi M, et al. Chronic kidney disease in children. Clinical Kidney J 2016;9:583–591.

- Schaefer F, Wingen Am, Hennicke M, et al. Growth charts for prepubertal children with chronic renal failure due to congenital renal disorders. European study group for nutritional treatment of chronic renal failure in childhood. Pediatr Nephrol 1996;10:288–293.

- Kaspar CDW, Bholah R, Bunchman TE. A review of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Blood Purif 2016;41:211–217.

- Rees L, Mak RH. Nutrition and growth in children with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2011;7:615–623.

- Mahesh S, Kaskel F. Growth hormone axis in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2008;23:41–48.

- Rees L. Growth hormone therapy in children with CKD after more than two decades of practice. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:1421-1435.

- Gil S, Vaiani E, Guercio G, et al. Effectiveness of GH treatment on final height of renal transplant recipients in childhood. Pediatr Nephrol 2012;27:1005–1009.

- Moreira JM, Bouissou Morais Soares CM, Teixeira AL, et al. Anxiety, depression, resilience and quality of life in children and adolescents with pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:2153-2162.

- Goldstein SL, Gerson AC, Goldman CW, et al. Quality of life for children with chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 2006;26:114-117.

- Gerson AA, Wentz MA, Abraham AG, et al. Health-related quality of life of children with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics 2010;125:349–357.

- KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease kidney international supplements 2012.

- Atkinson MA, Martz K, Warady BA, et al. Risk for anemia in pediatric chronic kidney disease patients: A report of NAPRTCS. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:1699–1706

- Ratcliffe LE, ThomasW, Glen J, et al. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in CKD: A summary of the NICE guideline recommendations and their rationale. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:548–558

- Nangaku M, Eckardt KU. Pathogenesis of renal anemia. Semin Nephrol 2006; 26: 261–268

- Fadrowski JJ, Christopher BP, Stephen RC, et al. Hemoglobin decline in children with chronic kidney disease: baseline results from the chronic kidney disease in children prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:457–462.

- Kurella TM, Vittinghoff E, Yang J, et al. Anemia and risk for cognitive decline in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2016;17: 13.

- Gerson A, HwangW, Fiorenza J, et al. Anemia and health-related quality of life in adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004;44:1017–1023.

- Mitsnefes MM, Kimball TR, Kartal J, et al. Progression of left ventricular hypertrophy in children with early chronic kidney disease: 2-year follow-up study. J Pediatr 2006;149:671–675.

- Parekh RS, Carroll CE, Wolfe RA, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in children and young adults with end-stage kidney disease. J Pediatr 2002;141:191–197.

- Groothoff J, Gruppen M, de Groot E, et al. Cardiovascular disease as a late complication of end-stage renal disease in children. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:123–126.

- Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, et al. Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: A report from the chronic kidney disease in children study. Hypertension 2008; 52:631–637.

- Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 2013;382:339–352.

- Flynn JT. Hypertension in pediatric patients with childhood-onset chronic kidney disease: much to be learned, more to be done. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1012-1013.

- Warady BA, Abraham AG, Schwartz GJ, et al. Predictors of rapid progression of glomerular and nonglomerular kidney disease in children and adolescents: the chronic kidney disease in children (CKiD) cohort. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:878–888.

- Hsu TW, Liu JS, Hung SC et al. Reno protective effect of rennin angiotensin- aldosterone system blockade in patients with predialysis advanced chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and anemia. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:347–354.

- Wühl E, Trivelli A, Picca S, et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 1639–1650

- Fine RN, Stablein D. Long-term use of recombinant human growth hormone in pediatric allograft recipients: A report of the NAPRTCS transplant registry. Pediatr Nephrol 2005;20:404–408.