Retention strategies: Exploring the use of value profiles to retain critical care nurses

Received: 16-Aug-2018 Accepted Date: Aug 29, 2018; Published: 07-Sep-2018

Citation: Maqbali MA. Retention strategies: Exploring the use of value profiles to retain critical care nurses. J Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2(3):26-31.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objective: To understand factors associated with critical care nurse turnover and explore potential strategies to improve retention of ICU nurses.

Methods: This exploratory qualitative study conducted interviews with 21 ICU stakeholders (administrators, physicians, and nurses) in Oman.

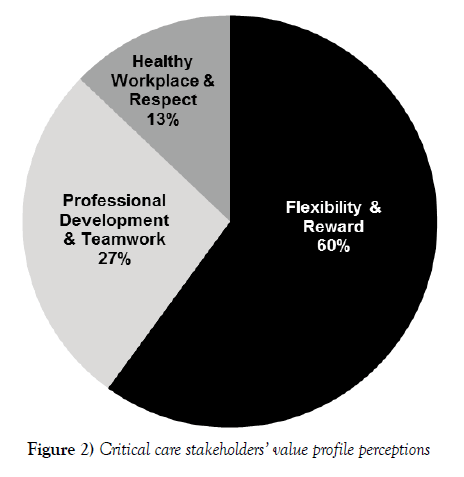

Results: While 60% of the recommended retention strategies focused on improved flexibility and rewards, suggestions varied depending upon the study participant’s role. Several critical care nurses recommended approaches that differed from the strategies described by administrators and physicians.

Conclusion: A one-size-fits-all, top-down retention strategy does not work well with critical care nurses who have diverse workforce needs. Hospital leaders should recognize how a nurse’s lifecycle position (based on age and experience) may influence his or her value profile. Leaders can empower ICU nurses by using a participatory decision-making process to develop customized retention strategies that align with critical care nurses’ individual value profiles.

Keywords

Critical care nurses; Primary health care

Introduction

The current shortage of critical care nurses is global and likely to persist [1-3]. Coping with nursing shortages is particularly challenging when hospitalized patients are acutely ill and require intensive nursing care [4]. In alignment with this need, the International Council of Nurses emphasized the importance of identifying an effective mix of staff and skills to ensure the deliverance of quality patient care [5]. Effective deployment of critical care nurses with requisite skills and experience is a high priority because they significantly influence the quality of services delivered to ICU patients [6]. Retaining critical care nurses requires greater understanding of the relationship between a nurse’s age/experience and his or her desire for flexibility and/or rewards [7]. In an effort to explore possible strategies to retain ICU nurses, this study evaluates the use of value profiles as a potential human resource tool to increase the retention of critical care nurses, which is a global challenge for healthcare organizations. During 2012, Northwestern Medicine reported a 15% turnover for critical care nurses in the state of Illinois [8,9]; while NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. (2016) reported an increase from 16.8% in 2014 to 17.7 % in 2015 for critical care nurses on average for all states in the U.S. This is on a par with bedside registered nurses, who in 2015 were reported to have a 17.2% turnover rate [10].

The process of calculating nurse staffing requirements is complex and challenging. Healthcare leaders must consider the types of service delivered, patient acuity, skill-mix, culture, leadership, and the healthcare team’s overall effectiveness. Hospital utilization and patient acuity increased in the 20th century [11] and research about patient safety has detected a strong relationship between nurse staffing and high patient morbidity and mortality rates [12]. Reid and Weller observed that nursing managers must engage meaningfully in an environment often characterized by ongoing workforce shortages, high turnover, absenteeism, and ever-growing demands for both quality and value in healthcare delivery [13].

Innovations aimed at improving nurse retention in talent acquisition and development can aid in creating more optimal work environments for nurses. In the UK, the Bolton Primary Health Trust implemented a successful nurse retention strategy that improved the nursing work environment [14] and improved health outcomes for patients. Factors affecting nursing performance may include reliance upon traditional recruitment, selection, and training practices, appraisal, compensation, employee relations, environment, workload assessment, and organizational structures that may impede effective work performance [15].

In every industry, leaders must consider the factors that affect individual performance when determining the quantity, quality, deployment, and utilization of human resources to deliver a service. In healthcare, nurse managers use specific tools to determine the appropriate quantity and quality of nurses needed to provide a required service. Examples of these tools include patient-to-nurse ratios, bed occupancy rates, patient acuity, skill mix, and patient classification systems [16,17]. To ensure appropriate use, these tools must be sensitive to the environment, culture, and needs of the organization.

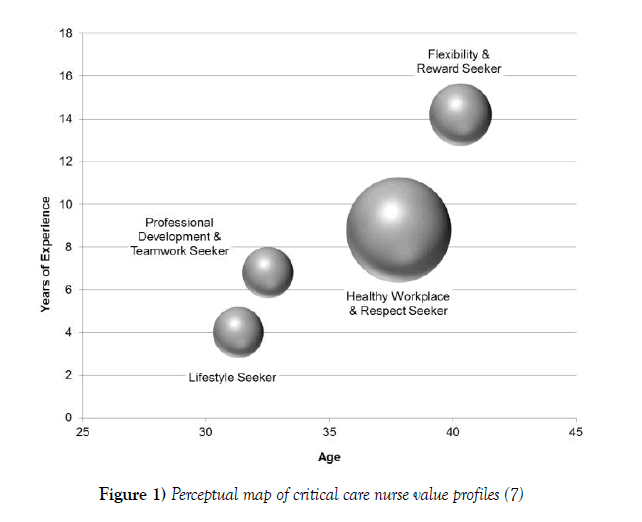

Lobo et al. suggest a one-size-fits-all approach to critical care nurse retention may be inherently flawed [7]. For example, Tourangeau, et al. found ICU nurses preferred retention strategies varied by his or her age and years of ICU experience [18]. Figure 1 includes a perceptual map of four distinct value profiles for ICU nurses [7]. The most experienced critical care nurses valued flexibility and rewards (Table 1), while mature nurses with moderate experience valued a healthy, respectful workplace. Younger nurses with moderate experience were motivated by professional development and teamwork, while those with the least experience valued lifestyle benefits, such as onsite amenities and employee discounts. Understanding these four value profiles may help healthcare leaders develop “an array of retention strategies [to meet diverse staff needs] rather than implementing a single solution” [7].

Figure 1) Perceptual map of critical care nurse value profiles [7]

| Value Profile | N | % | Age | Years of Experience | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | M | ||||

| Flexibility & Reward Seeker | 6 | 19% | 40.30 | 14.20 | Seeks recognition and compensation for work, desires option for self-scheduling, wants adequate nurse-patient ratios, and challenging innovative roles that leverage their experience |

| Healthy Workplace & Respect Seeker | 17 | 55% | 37.80 | 8.80 | Seeks a healthy, respectful work environment, wants reliable patient care equipment, a discounted parking rate, union support, interdisciplinary respect, and workplace ergonomics |

| Professional Development & Teamwork Seeker | 4 | 13% | 32.50 | 6.80 | Seeks a collaborative, respectful interdisciplinary team that is supported by management, wants continuing education, desires challenging innovative roles that take advantage of their experience, and wants higher pay for advanced knowledge and skills |

| Lifestyle Seeker | 4 | 13% | 31.30 | 4.00 | Seeks workplace amenities such as onsite fitness programs and/or 24-hour coffee shop, and desires employee discounts |

Table 1: Demographic & descriptive overview of critical care nurse value profiles [7]

Objective

This qualitative case study had three objectives. The first was to explore critical care stakeholders’ suggestions to improve the retention of ICU nurses. Data were collected from ICU nurses, physicians, and administrators in Oman. The second objective was to compare and contrast suggestions by role. The final objective was to analyze how, if at all, the current study’s findings differed from the value profile results reported in the literature [7].

A qualitative method was appropriate to study the critical care nurse shortage because it was unclear why high workloads persisted in Oman even though there appeared to be a sufficient number of ICU nurses [6]. Rather than using a quantitative approach, with close-ended questions that may not identify the root cause of the problem, an exploratory qualitative method was used to collect participants’ open-ended perceptions with semi-structured interviews [19].

Methodology

Sample

Stratified sampling identified 21 healthcare professionals who worked in three large ICUs in Oman. Nurses (n=7) in the sample were required to have a minimum of five years’ experience working in an ICU, a post-basic diploma in critical care, and at least one year of shift in-charge experience [20]. Participating physicians (n=7) were required to have minimum of three years of critical care experience. Healthcare administrators (n=7) included hospitals’ executive directors (EDs), directors of nursing (DONs), as well as their deputies.

Interview instrument

Data was collected in semi-structured open-ended questions during face-toface interviews with ICU professionals. A preliminary interview protocol was established with professionals within the Department of Nursing Affairs in Oman’s Ministry of Health for the sake of phrasing the research questions. The data collection instrument was then pilot tested with five ICU stakeholders from a hospital that was not included in the main study. This process helped verify the context, specific meanings, potential ambiguity, and cultural appropriateness of question phrasing. After assessing the validity and clarity of the protocol’s phrasing, the semi-structured data collection instrument was finalized. The original interview protocol, which contained 11 open-ended questions, was part of a larger study [21]. Data from only one question was analyzed in the current study: What can hospital management do to improve the management and retention of ICU nurses at your hospital?

IRB approval

The study was approved by the Research and Ethical Review and Approve Committee for the Directorate of Research and Studies in Oman’s Ministry of Health. Information about the purpose of the study and data collection process was shared with each participant prior to obtaining consent to participate. No identifying information was collected, and participants were assured their responses were confidential and anonymous.

Data collection

To ensure accuracy, interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Each participant then reviewed his or her information to validate the correctness of the data [22-25]. In alignment with IRB guidelines, information that might identify subjects was omitted from all transcripts.

Data analysis

Three graduate level coders (the primary researcher and two trained coders) reviewed the data. Because it was possible for participants to make multiple comments when responding to each question, all comments were analyzed as the study’s unit of analysis. The number of comments made by each participant varied by question. Themes were identified, and individual comments were categorized. Each coder’s theme frequencies were then tallied. A Cronbach’s alpha determined an inter-rater reliability score for each coder’s frequencies. Coding by the three independent raters produced a Cronbach’s alpha of .91, which is considered highly reliable [19].

Results

ICU stakeholder suggestions

A majority of ICU stakeholders’ comments (60%, n=42) proposed improving the management and retention of ICU nurses by using strategies aligned with the flexibility and reward profile (Figure 2). As shown in Table 2, a content analysis of interview transcripts from 21 critical care stakeholders revealed five subthemes related to flexibility and rewards. Most comments (21%, n=15) described the need to increase the number of ICU nurses. In particular, some interviewed stakeholders stressed the importance of maintaining a 1:1 nurse-to-patient ratio.

| Critical Care Nurse Value Profile | Subthemes | Themes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Flexibility & Reward Seeker | 42 | 60% | ||

| Increase the number of ICU nurses | 15 | 21% | ||

| Hospital policies | 9 | 13% | ||

| Improve pay | 8 | 11% | ||

| Increase recognition | 6 | 9% | ||

| Hire experienced nurses | 4 | 6% | ||

| Professional Development & Teamwork Seeker |

19 | 27% | ||

| Increase support staff & collaboration | 9 | 13% | ||

| Improve education & training | 7 | 10% | ||

| Manage new ICU nurse expectations | 2 | 3% | ||

| Improve communication with patients and family | 1 | 1% | ||

| Healthy Workplace & Respect Seeker | 9 | 13% | ||

| Improve resources (supplies, equipment) | 5 | 7% | ||

| Improve facilities | 4 | 6% | ||

| Lifestyle Seeker | 0 | 0% | ||

| Total | 70 | 100% | 70 | 100% |

Note: Participants often had more than one open-ended response to the question. As a result, the study's unit of analysis was the comment.

Table 2: Frequency of participants’ suggestions to improve the management and retention of ICU nurses

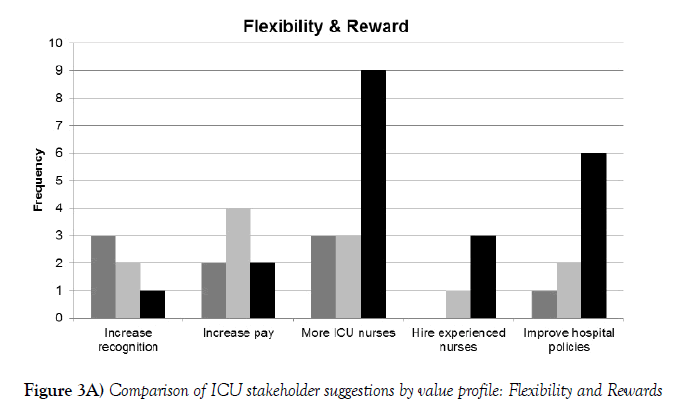

Other comments (13%, n=9) emphasized the need to change hospital policies, such as admission and discharge procedures. Improving pay (11%, n=8), increasing recognition (9%, n=6), and hiring experienced nurses (6%, n=4) were also mentioned by ICU stakeholders in the study. One nurse explained that junior nurses “have not been trained for the ICU. They are unable to provide proper patient care. Their basic training doesn’t qualify them to care for acute patients in the ICU or be able to cope with the ICU culture. For this study, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, junior nurses will be those with less than five years of experience in an ICU. Another participant reported, “Most of the staff nurses currently do not have a [critical care] specialization and they only have two to three years’ experience. Junior nurses lack experience and demand assistance which increases the work load [for senior nurses].”

Additionally, study participants described low recognition of ICU nurses as well as limited opportunities for advancement. Some critical care stakeholders in the study indicated ICU nurses are rarely appreciated or promoted for their hard work. Several participants also reported that ICU nurses are required to work harder during inconvenient hours, such as during night shifts (21:00-07:00), yet these nurses received the same compensation as other nurses with fewer responsibilities. One nurse explained, “There are no promotions for ICU nurses and no special compensation. If I receive the same salary, why would I want to work in ICU where I will have to work the night shift?” Flexibility, in particular, was valued. “When nurses first come to [the] ICU, they are single,” one nurse participant explained. “Then they get married and have children. So they look for a better job with less night duties because they don’t have anyone to take care of their children.”

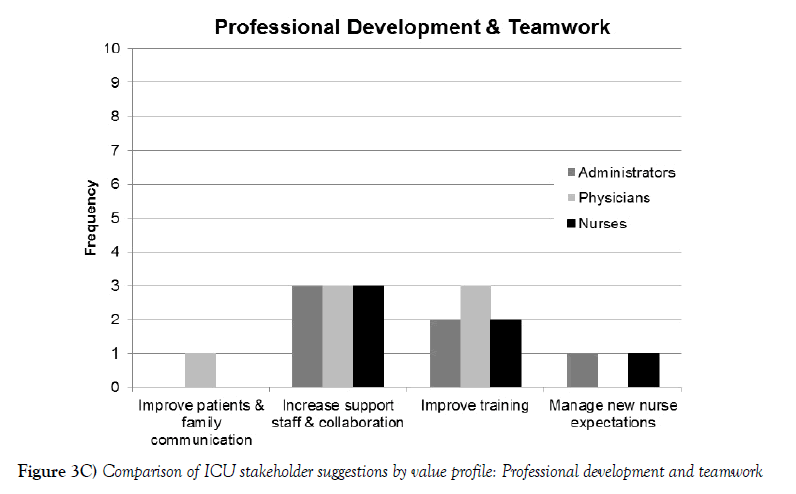

About a third of the recommendations from ICU stakeholders (27%, n=19) aligned with the professional development/teamwork value profile. Most of these suggestions (13%, n=9) described the need for increased support staff and collaboration. One physician in the study explained that ICUs need more phlebotomists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, medical orderlies, and social workers to assist critical care nurses. One nurse explained, “We spend time answering the phone, collecting blood, or going to the lab” rather than providing direct patient care. Another nursing professional reported, “There is no security in the ICU; so, nurses spend time controlling visitors.” Another 10% of the comments (n=7) emphasized the need for training. One physician recommended offering more opportunities for local as well as expatriate nurses to get a post-basic certification in critical care. Improved communication and collaboration with new nurses (3%, n=2) as well as patients and families (1%, n=1) were also mentioned.

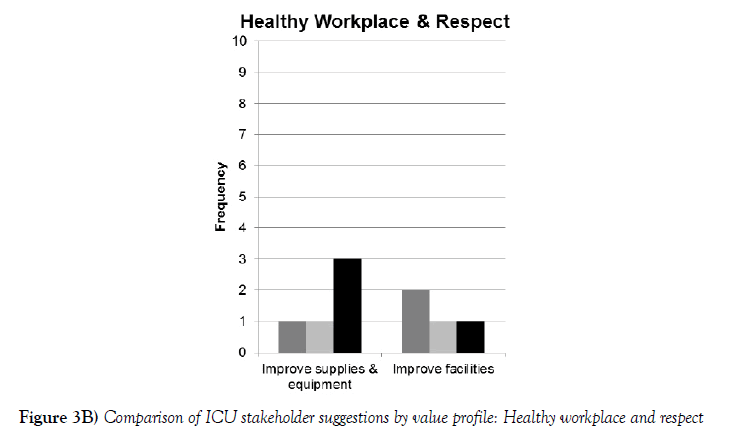

Some comments from ICU stakeholders in the study related to creating a healthy, respectful workplace (13%, n=9). One physician explained that ICU nurses face tremendous workloads with risk of back injuries. “Most of them are totally stressed in the ICU. It should not be like that. There should be a comfortable work environment, so nurses can provide good and safe care.” A hospital administrator similarly observed, “Nurses are getting backaches from lifting heavy patients in the ICU.” Study participants described the need for additional beds, supplies, computers, cardiac monitors, diagnostic and intubation equipment (7%, n=5). Other comments focused on the need to improve the physical facilities (6%, n=4). None of the suggestions related to the lifestyle value profile (Table 2).

Differences by role

Some ICU stakeholder suggestions varied by role. As shown in Figure 3A, the frequencies of comments about the three value profiles relevant to this study (healthy workplace/respect, professional development/teamwork, and lifestyle seekers) were similar. However, critical care nurses in the study reported more flexibility and reward suggestions (50%, n=21) than other participants (physicians, 29%, n=12; administrators, 21%, n=9). Nurse leaders suggested the use of additional ICU nurses (n=9) more frequently than administrators (n=3) or physicians (n=3). Nurses (n=6) also recommended changes in hospital policies more frequently than physicians (n=9) or administrators (n=9).

Comparison with a similar value profile study

Figure 3B compares the recommendations of the critical care nurses in this study with Lobo et al. findings. While a similar percentage of ICU nurses in both studies mentioned the importance of professional development and teamwork, there were larger gaps with the remaining three value profiles. Only 19% of the ICU nurses in Lobo et al. study (compared to 68% in the current study) felt flexibility and reward was important (a 48% gap). In contrast, 55% of critical care nurses in Lobo et al.’s study (compared to 13% of ICU nurses in this study) were motivated by a healthy workplace/respect (a 42% gap) [7]. While 13% of the nurses in Lobo et al. study reported a preference for the lifestyle profile, none of the ICU nurses in the current study expressed a similar preference.

Discussion

Like many countries, Oman suffers from a significant nursing shortage [26]. With an insufficient number of experienced nurses, ICU workloads and undesirable schedules frequently result in high nurse dissatisfaction [27]. To maximize patient outcomes, it is imperative for healthcare leaders to identify and implement innovative strategies that retain critical care nurses. Data from the current study suggests understanding lifecycle needs, using segmented approaches, and empowering participatory decision-making may improve retention of ICU nurses.

Understanding lifecycle needs

Findings from the current study suggest ICU nurses’ transition through various lifecycles during their careers. Participants’ open-ended comments provided evidence that younger nurses, typically with less ICU experience and no children, often have different work priorities than older nurses with more experience and larger families. This finding is consistent with Lobo et al. study that reported an association between a nurse’s age/experience and his or her desire for flexibility/reward as well as Tourangeau et al. identification of distinct value profiles based on a nurse’s age and years of experience [18]. Younger ICU nurses may focus predominantly on enjoying life, while their older, more experienced counterparts may value scheduling and/or compensation to help support a family and/or career. Similarly, inexperienced nurses may not fully understand the clinical demands of working in an ICU as described in previous research, namely the “excessive workload, high patient care demands, time pressure and intensive use of sophisticated technology” are aspects leading to burnout of critical care nurses [28]. As they mature and gain experience, their desire for professional development and education may also increase. This approach is consistent with Wieck et al. study that used generational profiles (veterans, baby boomers, Generation X, and millennials) to identify differences between each age group [29]. In turn, the researchers were able to determine how attitudes, behaviors, and expectations within each age group affected job satisfaction and retention [29].

Using segmented approaches

Based on the diverse lifecycle needs of critical care nurses, an aggregated ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is unlikely to meet the workforce needs of ICU nurses. Instead, segmented retention strategies are likely to be more effective. Data from the current study were consistent with the existence of distinct critical care nurse segments (e.g., new/young nurses, middle aged/mid-career nurses, mature/experienced nurses) — each with specific workload concerns that align with their value profiles. For instance, healthy workplace/respect seekers may be more inclined to remain with organizations with quality equipment/facilities and sufficient support staff. In contrast, flexibility/ reward seekers might be more likely to stay when they receive adequate financial compensation, advancement opportunities, and consistent appreciation. While some concerns may overlap with more than one value profile (e.g., adequate training may be a concern of both flexibility/reward as well as professional development/teamwork seekers), leaders should avoid generic conventional approaches that are unlikely to meet the unique needs of specific segments.

Empowering participatory decision-making

Historically, healthcare leaders — not frontline nurses — are in charge of developing strategies to retain ICU nurses. Data from the current study suggests such top-down decisions, with little or no direct input from frontline staff, may result in misaligned strategies that fail to address the concerns of ICU nurses. In the current study, healthcare administrators, physicians, as well as ICU nurses were asked to identify strategies to overcome critical care staffing shortages. If HR leaders examined all the potential solutions identified in Figure 3C, it might be difficult to select the best options. HR leaders, because they may be far removed from the realities of an ICU, should collaborate with critical care managers and nurses to assess the potential effectiveness of each strategy.

If HR interventions were developed based solely on the aggregated findings of the current study, significant portions of the ICU workforce might be overlooked. For instance, none of the ICU stakeholders in the current study expressed lifestyle concerns. Nevertheless, the retirement of many older ICU nurses and entry of millennial-age caregivers may result in younger nurses with lifestyle concerns. Lobo et al. study found fitness centers, coffee shops, and other staff perks could be important to critical care nurses who are lifestyle seekers [7]. If segmented approaches are used to customize retention strategies for nurses with similar value profiles, the likelihood of satisfying the workforce needs of individual nurses may be higher.

To this end, healthcare leaders should consider increased use of participatory decision-making to maximize retention of nurses [18,30,31] urged caution against “quick fixes,” instead suggesting healthcare leaders speak “directly with mature workers to understand their issues and needs” (p. 467). For instance, Derbyshire described an intervention that required the participation of critical care nurses in a leadership discussion of retention practices [14]. This process led to the eventual implementation of flexible work schedules, staff recognition programs, phased-in retirement options, support for finding childcare, and education funding access — all of which aided in reducing turnover. Dwyer, Jamieson, Moxham, Austen and Smith similarly described how critical care nurses were asked to provide feedback about the implementation of a 12-hour roster at a regional ICU [32]. This single change in shift flexibility increased continuity for patient care while also improving the physical and psychological well-being of ICU nurses [32]. The success of such participatory strategies suggest healthcare HR leaders should consider bottom-up approaches that allow critical care nurses to customize retention strategies, rather than imposing top-down retention approaches. For instance, ICU nurses with children may place more value on scheduling flexibility that allows them to maintain a better work/life balance, while specialized training may appeal to healthy workplace/respect as well as professional development/teamwork seekers.

Nursing Implications

The study’s findings suggest critical care nurses may be in the best position to identify innovative retention solutions. In their study of acute care nurses, Downey, Parslow and Smart described informal leaders as the “hidden treasure in nursing leadership” (p. 517) [33]. While such leaders are currently empowered to make clinical decisions, the findings of this study suggest informal leaders could play a pivotal role in HR policies as well. Downey et al. argued, “Nursing needs energetic, committed and dedicated leaders to meet the challenges of the healthcare climate and the nursing shortage. This requires nurse leaders to consider all avenues to ensure the ongoing profitability and viability of their healthcare facility” (p. 517). Krueger similarly suggested that informal leaders are critical to the change process [34].

To succeed, hospital leadership should foster an environment of participatory decision- making by encouraging critical care nurses to help identify strategies that may increase retention. In turn, ICU nurses must be willing to reflect on the root causes of critical care nurse turnover and discuss strategies to increase ICU nurse retention. In addition to their personal experience, critical care nurses should consider strategies that align with the four value profiles identified in the literature. After identifying strategies, critical care nurse should communicate their ideas to hospital leaders and other ICU stakeholders [7]. Nurses should also act as change agents to promote adoption of effective retention strategies.

Limitations

Various factors limit the generalizability of the study’s findings. The results were limited to the self-reported perceptions of 21 stakeholders at three major hospitals in Oman. Stakeholders at other Omani ICUs, as well as representatives from critical care units in other countries, may have different perceptions about nurse staffing. Study participants were also limited to health administrators, physicians, and nurses. Other stakeholders, such as patients, family members, medical orderlies, physiotherapists, laboratory technicians, social workers, and respiratory therapists, were not interviewed. It is not clear whether the inclusion of their insight may have resulted in different findings. Finally, the use of face-to-face interviews may have influenced the candor and openness of study participants [35].

Conclusion

Despite years of effort to address the issue, the critical care nurse shortage continues to be a global workforce problem. Interviews with ICU stakeholders in the current study identified a variety of strategies that may increase the retention of critical care nurses. However, when evaluating the potential effectiveness of each approach, critical care leaders should avoid one-size-fits-all solutions that are unlikely to appeal to a diverse workforce. Instead, healthcare leaders should recognize that nurses are motivated by different values that influence their likelihood of staying in the role of a critical care nurse. When the retention of every ICU nurse matters, it is essential for healthcare leaders to adopt innovative approaches that actively involve frontline ICU nurses in the development of customized retention strategies.

REFERENCES

- Williams G, Chaboyer W, Thornsteindottir R, et al. Worldwide overview of critical care nursing organisations and their activities. Int Nurs Rev. 2001;48(4): 208-17.

- Friedman MI, Cooper AH, Click E, et al. Specialised new graduate RN critical care orientation: Retention and financial impact. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(1): 7-14.

- Gohery P, Meaney T. Nurses’ role transition from the clinical ward environment to the critical care environment. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29(6): 321-8.

- Ayala E, Carnero A. Determinants of burnout in acute and critical care military nursing personnel: A cross-sectional study from Peru. 2013;8(1): e54408.

- https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdfen/staff_mix_literature_review_e.pdf

- Directorate of Nursing and Midwifery Affairs: Human resources framework; Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health. 2012.

- Lobo V, Fisher A, Baumann A, et al. Effective retention strategies for midcareer critical care nurses. Nurs Res. 2012;61(4): 300-8.

- https://www.nmh.org/nm/quality-Turnover-CritCare

- Kovner CT, Brewer CS, Fatehi F, et al. What does nurse turnover rate mean and what is the rate? Policy, Polit Nurs Pract. 2014;15: 3-4.

- http://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Files/assets/library/retentioninstitute/NationalHealthcareRNRetentionReport2016.pdf

- Hoi S, Ismail N, Ong L, et al. Determining nurse staffing needs: The workload intensity measurement system. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(1): 44-53.

- https://www.msh.org/sites/msh.org/files/HRM-Health-Action-Framework 7-28-10 web.pdf

- Reid A, Weller B. Nursing human resources planning and management competencies.

- http://www.bolton.nhs.uk/Library/strategies/RRS.pdf

- Fried B, Fottler M. Human resources in healthcare. Chicago: Health Administration Press. 2008.

- Acar I. A decision model for nurse-to-patient assignment [dissertation]. Phoenix, AZ: University of Phoenix School of Advanced Studies. 2010.

- Siew CTS, Ghani NA. An overview of nurses workload measurement systems and workload balance. Proceedings of the 2nd IMT-GT Regional Conference on Mathematics, Statistics and Applications.

- Tourangeau A, Patterson E, Rowe A, et. al. Factors influencing home care nurse intention to remain employed. J of Nurs Manag. 2013;22(8):1015-26.

- Creswell JW. Research Design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 2009.

- Trochim WMK. Non-probability sampling: Research Methods Knowledge Base Website. 2015.

- Al-Maqbali M. Perceptions of ICU stakeholders toward nursing staff levels in Omani hospitals: A qualitative case study [dissertation]. Phoenix, AZ: University of Phoenix School of Advanced Studies. 2013.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2008.

- Cooper DR, Schindler PS. Business research methods. 12th edn. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Irwin. 2013.

- Creswell JW. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 4th ed. Columbus, OH: Merrill-Prentice Hall. 2013.

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. 5th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 2013.

- Directorate of Nursing and Midwifery Affairs: Strategic planning. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health. 2010.

- Reid UV. Oman mission report: Nursing and midwifery human resources planning framework; Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health. 2010.

- Bakker AB, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. JAN. 2005;51(3): 276-87.

- Wieck K, Dols J, Northam S. What nurses want: The nurse incentives project. Nurs Econ. 2009;27(3): 169-201.

- Upenieks V. Recruitment and retention strategies: A magnet hospital prevention model. Medsurg Nurs. 2003;21(1): 21-7.

- Hirschkonrn C, West T, Hill K, et al. Experienced nurse retention strategies: What can be learned from top-performing organizations. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(11): 463-7.

- Dwyer T, Jamieson L, Moxham L, et al. Evaluation of the 12-hour shift trial in a regional intensive care unit. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15(1): 711-20.

- Downey M, Parslow S, Smart M. The hidden treasure in nursing leadership: Informal leaders. J Nurs Manag. 2011;19(4): 517-21.

- Krueger DL. Informal leaders and cultural change. Am Nurse Today. 2013;8(8).

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: 3rd edn, Sage Publications. 2012.