Safeguarding children and young people in the online environment: Safeguarding implications in respect of sexting and associated online behaviour

Received: 01-May-2018 Accepted Date: May 10, 2018; Published: 17-May-2018

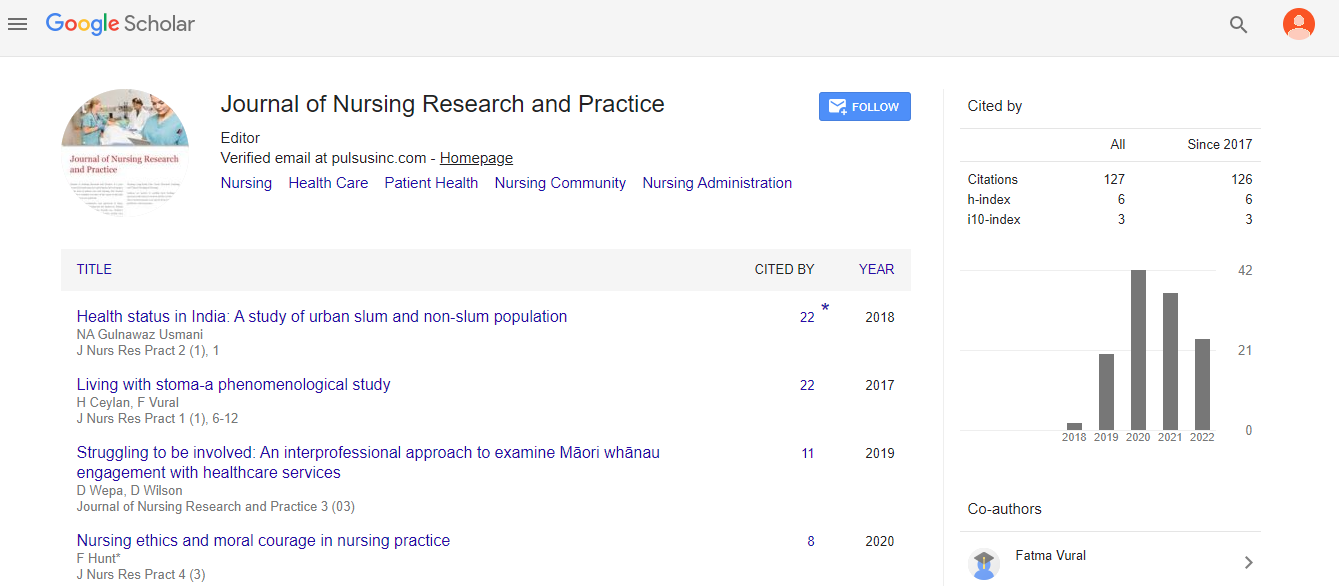

Citation: Murray S. Safeguarding children and young people in the online environment: Safeguarding implications in respect of sexting and associated online behaviour. J Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2(2):26-29.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Between November 2014 and 2017, police forces across the United Kingdom reported a 131% (England and Wales) and 60% (Scotland) rise in the recorded indecent communications online or via texts since the inception of the Sexual Offences Act (England, 2003: Scotland, 2010). Nurses, social workers, educationalists and allied health professionals, have received minimal training in respect of sexting, resulting in missed opportunities to identify those at risk of online sexual exploitation. Deliberation continues regarding the risks associated with such communications and the necessity for vigilance in protecting those at risk. This article reviews literature and legislation to consider the extent by which sexting should cause concern, characteristics of perpetrators and victims, risk reduction, and the appropriateness of criminalising young participants. Literature suggests misappropriated sexting places vulnerable individuals in danger of sexual extortion, bullying and mental ill-health, and that adolescent females are at greater risk than males of being coerced into sexualised behaviour. Associations between prevalence of sexting and inappropriate sexual behaviour are noted, with limited parental and professional awareness of the subject compounding young peoples’ vulnerability. The article questions the validity of criminalising consensual sexting and considers an educational and supportive approach to be more appropriate.

Keywords

Sexting; Online behaviour; Safeguarding

Introduction

On the 10th anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), UNICEF’s Oslo Challenge noted that maximising online opportunities is a matter of children’s rights [1]. They expanded this concept by stating; ‘the child-media relationship is an entry point into the wide and multifaceted world of children and their right to; education, freedom of expression, play, identity, health, dignity and selfrespect, and protection’ [2]. Whilst acknowledging the right of the child to access such online opportunities, at the time the Oslo Challenge was written the potential risks associated with such freedoms were inconceivable.

In June 2016, Police Scotland reported a 10% rise in the number of recorded indecent communications online or via text since the inception of the 2010 Sexual Offences Scotland Act. The Act made it a criminal offence to send any sexual message to children. According to Ford, Head of Service for the NSPCC Scotland (NSPCCS), this figure is significantly unrepresentative of the scale of the problem, and endorses fears that technology poses an increasing sexual abuse threat to younger children across the United Kingdom (UK) [3]. During 2015/16, 43% of the children contacting the NSPCCS helpline had experienced sexual abuse, with online and text related sexual abuse becoming an increasing cause for concern. Figures from the NSPCCS and ChildLine counselling sessions, reflect a 60% rise in such cases over the past six years [3]. Ford, and the Police Scotland National Child Abuse Investigations Unit, highlight this does not include unreported instances of online or text related sexual abuse.

‘Sexting’, the sending, receiving, or forwarding of sexually explicit photographs or messages via mobile technology, is a relatively recent phenomenon, with the potential to have catastrophic and long-term influences on those concerned [4]. For vulnerable individuals, sexting may result in unhealthy pathological use of the internet and place them at risk of significant harm [5]. Diliberto and Mattey discuss the need for awareness of this subject amongst nurses working with children and young people, in addition to the development of appropriate training and education programmes [4].

Nurses working in schools, child health settings, or with young people who have additional learning needs or mental health issues, are well placed to identify children at risk of online sexual exploitation. Until recently nurses received minimal training in respect of online abuse and there remains a lack of awareness of the subject, particularly of sexting, resulting in missed opportunities to support those affected. Programmes have been developed across the UK to redress this situation, with Public Health England and the Department of Health presenting a new pathway in 2017 to support school nursing in reducing sexual exploitation. Lewis et al. (2017), in a report for the Burdett Trust for Nursing, note there is an urgent need for enhanced practice education about sexting and the associated impacts of harmful sexual behaviour. This article examines the expanding literature about sexting, the degree to which it should cause concern, characteristics of both perpetrators and victims, legislative issues, risk reduction, and support systems.

Sexting and online vulnerability

The term sexting was first reported in 2005. Initially this involved text-based written material of a sexual nature, unlike the present use of photographs and video, and is sometimes referred to as ‘home-made pornography’ [6]. Distinct from ‘para-sexting’ (the sending of nude or pornographic material relating to an unknown individual), sexting involves at least in the initial stages, the sharing of material between familiar individuals [7,8].

Albury et al., argue that not all young people utilise the term sexting, and whilst occurrences of misuse and the potential for bullying must be taken seriously, there should be recognition as to the context, the role of sexting in contemporary ‘flirting’, and the culture in which the act takes place [6]. Olweus, acknowledged for his work in the United States (US) on reducing bullying in schools, views that whilst concerns are legitimate, the media and some researchers have inflated the level of the problem [9]. In contrast, Temple, Paul, Van den Berg and McElhany and O’Keeffe and Clarke-Pearson warn practitioners of the potential for risk-taking sexual behaviours, especially amongst female participants [10]. Evidence suggests misappropriated sexting places vulnerable individuals at risk of sexual exploitation, extortion, and depression [11,12]. Reports of incidents of online ‘grooming’, noted these were primarily, ‘inciting a child to perform a sexual act’ (34%) and ‘inciting a child to watch a sexual act’ (20%) [13,14]. Arguably, incitement has occurred when an adolescent requests a younger child sends them a sexual image.

Figures in respect of young peoples’ engagement in sexting vary, with higher levels of research being undertaken in the US than the UK. As an evolving phenomenon, it is likely that evidence will be rapidly outdated, and as such the following data is most probably conservative. 91% of 12 to 17-yearolds UK children have their own mobile phone, 75% of 5 to 7 year olds have access to mobile phones and use the internet, and one-in-four 8 to 12 year olds have their own social networking page [15,16]. An online study involving 535 children aged 13 to 18 years from the South West of the UK, reported 40% of those interviewed had friends who engaged in sexting, 24% stated sexting is a regular occurrence, and only 7% had no knowledge of sexting incidents amongst peers [17]. These statistics mirror those of a UK wide survey of 2094 adolescents, where 25% of respondents reported receiving unwanted sexual images [18]. The shift in mobile-technology usage to include younger individuals, means discussion around risk factors must involve primary school children [19,20]

Discussion

Having an understanding as to why children and young people partake in the self-production of sexual images is beneficial to policy makers, educationalists, and relevant professionals. It is inappropriate to suggest that those who sext will necessarily become victims of online sexual exploitation, however it is pertinent to compare lower-risk sexting behaviours in relation to those which place the individual at high-risk of online grooming. A large-scale US survey undertaken in 2009, found that 60% of participants sent sexual images to a girl/boyfriend, with 22% sending sexually suggestive images to ‘someone they had a crush on’. Reasons for participating in such activities included; ‘because they were asked to’ (43%), and ‘just having fun’ (40%). 65% of sext senders were girls responding to requests from males [4]. Whilst UK figures suggest the issue to be marginally less prevalent the reasons for such behaviours, and the coercion of girls into sending sexual images reflected similar approaches [21-23]

The perception by a significant percentage of young people that sexting is ‘just having fun’, permeates a number of studies. Where the practice is consensual, sexting may be considered as an expression of teenage sexual agency [24,25]. Risk-taking within healthy boundaries supports resilience, this may include accessing online and offline risk opportunities. However, the line between sexting and cyberbullying is contentious [26]. Sexting is a voluntary act, cyberbullying is deliberate and harmful. If a sext is intentionally shared without the expressive permission of the sender, an unacceptable act has taken place. Approximately one in five sexts are forwarded to another party, and peer pressure appears to be a key motive for sending sexually explicit texts [27,28]. Neither of these suggests voluntary acts or informed consent.

The impact on an individual whose text message is viewed beyond the intended recipient may be profound. This is particularly the case for those with low self-confidence and who lack resilient and supportive family and friends. For these individuals, an isolated misappropriated image places them at considerable risk of cyberbullying and its associated physical injury and mental trauma [29]. Data specifically associated with sexting related cyberbullying is limited, however reports include a sense of extreme shame, school failure, psychiatric conditions, mood disorder, and suicide [30-32].

Resilient young people who are well supported by family and friends, and whose sexual images remain with the intended recipient, may be unscathed by their practices, others may become socially marginalised, victims of sexual predators, or inadvertently drawn into illegal practices [33-35]. The Cox Communications study (2009) found that 11% of surveyed youngsters sent an image to someone they had met online but did not know personally. This high-risk taking behaviour was apparent in European and UK research [21]. Family difficulties, abuse and neglect, experience of the care system, engaging in drug and alcohol misuse, socialisation or sexual identity issues, gang involvement, and school truancy, increased vulnerability. A consistent factor across studies related to children who had extended periods alone and lacked appropriate adult intervention [36-38]. A small-scale study found that being female, having additional learning needs, and mental health issues, either personally or within family, were significant risk factors [39,40]. However, Palmer discusses that some of the individuals she worked with would not fit into any of the offline-risk categories, and therefore caution must be taken not to generalise when assessing for risk and protective factors.

Korenis and Billick and Temple report a relationship between sexting, actual sexual relations, and unplanned teenage pregnancies [31,5]. For both boys and girls in the study group, the sending of explicit sexual messages increased the likelihood of sexual relationships by 37% and 35% respectively. Young people who participate in sexting, and who text frequently, are more likely to sext frequently. This regular exposure to sexual material places them at risk of using social media to meet their sexual needs, without the formation of caring personal relationships. Hackett considers there to be ‘legitimate concerns about the impact of early sexualisation of children through exposure to online material’ [41]. The creation of ‘the self’ as a sexual object, and the mainstreaming of pornography (pornification) appears to place young people at risk of engaging in casual and unhealthy sexual behaviours [42,43,23].

A trans-European study aimed at assessing online practices of European children, used a random stratified sample of circa 1,000 children across 25 countries. The results in respect of the child’s vulnerability reflected the smaller studies identified above, however the role of the parent/s was insightful and worthy of further discussion [21]. Parents with limited understanding of digital safety, or who decline to recognise the risks and respond accordingly, were significantly less well placed to protect their children. Similarly, parents who are educationally, economically, or linguistically disadvantaged, lacked the confidence to access professional support. Virag and Parti present the findings of the Budapest study, they consider that young people in countries joining the European Union after 2004, including Budapest, are less supported by their parents regarding online safety, and are thus more at risk of partaking in risk-taking online behaviour [44].

Sexting and online vulnerability should be considered in the context of the child and young person’s life [45]. There is increasing concern regarding young people who sext beyond the parameters of the school environment, and whilst not consistently the case, there appears to be a correlation between low self-esteem, reduced life chances, and vulnerability, to partaking in a range of unhealthy and high-risk taking behaviours. The European Online Grooming Project (2009-2012) considered potential sexual victims under the following categories; ‘Disinhibited’, willing to interact, send provocative images or texts, but unlikely to meet, or be blackmailed by offenders; ‘Vulnerable’, (the minority) willing to interact, seeking relationships/friendship, and at high risk of meeting with perpetrators, and; ‘Resilient’ (the majority) least likely to interact, low risk of meeting potential abusers [46].

Abuse

Abuse is ‘a deliberate act of ill treatment that can cause harm or is likely to cause harm to a child’s safety, well-being and development’ [47]. Applying this or similar definitions to the deliberate sharing of another individual’s sexual image equates to child abuse. European, UK, and US studies note that there is a lack of clarification in respect of the law and sexting [48-51, 28]. This situation is compounded by the continuing changes in technology, and the complexities regarding developing laws too hastily. In the US, sexting is positioned under the category of felonious child pornography if the perpetrator is under 18 years. ‘Participating teenagers are at risk of strict legal consequences, possible prison sentences, and being registered as a sex offender’ [52].

491 juveniles (8.2% of all sexual crime) in England and Wales were convicted of sexual offences in 2013 (Ministry of Justice, 2013). This figure excludes children under ten years, or those who had been involved in child protection services. Interviews with criminal justice professionals reflect that within-peer grooming involving sexting, represents an increasing number of cautions and convictions amongst 13-17-year old [53,54]. Disquiet regarding the risk of criminalising sexting includes concerns that sexting may be safer than face-face sexual intimacy and should be regarded as ‘sexual expression’, and protected under human rights laws. This view does not include any attempt to harm on behalf of the perpetrator [48,55].

Livingstone poses that it is beneficial to balance ‘children’s freedoms’ against ‘children’s protection’, as both of these are incorporated within a children’s rights framework [56]. Livingstone cites Berlin’s (1969) belief that the concept of freedoms should be interpreted as both positive and negative, and that empowering children involves giving appropriate access to information yet accepting the need for regulation and restriction. There is sufficient evidence regarding risks associated with early sexualisation, links to pornography, and unhealthy sex practices, to satisfy that a proactive approach to this issue is valid. Some situations will require immediate intervention to reduce the risk of harm. For others, developmentally sensitive, individual, and holistic practices, based on strengths and attending to both risk and need are appropriate [41,57]. Understanding typical age appropriate sexual behaviours, supporting young people to make positive decisions, and promoting supportive peer relationships are likely to be more productive than instigating harsh punitive approaches [58,59].

Conclusion

In conclusion, access to digital technology, including mobile phones, has resulted in a shift in the way a significant percentage of young people engage with their sexual peers. Caution in interpreting the level of risk is relevant, however there exists a plethora of evidence to support concerns that used inappropriately, sexting may cause considerable harm to those involved [53,33,59]. Early sexualisation may impact an individual’s ability to engage in meaningful associations, and combined with the use of fantasy, particularly if reinforced by online relationships and images, places susceptible individuals at risk [42].

For some members of society sexting may be an acceptable experience, however for vulnerable youngsters the risks, both short and long-term, are considerable. Factors which place children at risk from sexting are similar to those which reduce life chances per se, and include social isolation, lack of support from family, mental health issues, additional learning needs, and a history of abuse [37,60]. There is a clear gendered dimension to sexting, perpetrators are more likely to be male and the victim female, a fact which has long been associated with sexual repression and the objectification of women as sex-objects [39]. Responses to sexting should be considered, and mindful of the fact that some young people do not ‘fit’ the offline risk categories identified above. Assessment of risk, and meaningful support and education programmes which acknowledge the context of an individual’s life, are more likely to produce positive results than an insistence on abstinence and attempts to criminalise young people [45,61-73].

Key practitioner messages:

• Necessity for increased awareness of sexting and associated behaviours amongst health, social care and education professionals

• Appropriate training and education opportunities required to identify those at risk of online sexual exploitation

• Broader understanding as to why children and young people partake in the self-production of sexual images is essential

• Caution must be taken not to generalise when assessing for risk

REFERENCES

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child: UNICEF’s Oslo Challenge. 1989.

- Livingstone S. Children and the internet: Great expectations, challenging realities; Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. 2009.

- Ford M. Improving our response to children at risk of abuse: Paper presented at the NSPCCS Rebuilding childhood conference. 2016.

- Diliberto GM, Mattey E. Sexting: just how much danger is it and what can school nurses do about it? NASN School Nurse. 2009.

- Temple J. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviours. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;101: 834-5.

- Albury K, Funnel N, Noonan E. The politics of sexting: Young people, self-representation and citizenship; Paper presented at the Media Democracy and Change. 2010.

- Jacobs D, Verniero PG. Sexting hardly constitutes child endangerment. 2009.

- Kasparian A. Mobile Porn becoming the norm in schools? 2009.

- Olweus D. Cyberbullying: An over rated phenomenon? Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012;9: 520-38.

- Temple J, Paul J, Van den Berg P, et al. Teen Sexting and its associated sexual behaviours. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166: 828-33.

- Houck C, Barker D, Rizzo C, et al. Sexting and sexual behaviour in atrisk adolescents. Pediatr. 2014; 33: 276-82.

- Quayle E, Newman E. The role of sexual images in online and offline sexual behaviour with minors. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2015;17: 43-54.

- Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre; Strategic Assessment Report on Child Trafficking. 2009.

- Spielhofer T. Children’s online risks and safety: a review of the available evidence. UK Council for child internet safety, NfER. 2010.

- Byron T. Do we have safer children in a digital world? A review of progress since the 2008 Byron report, Nottingham, UK: DSCF Publications. 2010.

- Ofcom. Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report. 2016.

- http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/media-literacy/children-parents.

- http://impact.Ref.ac.uk/casestudies.

- Cross EJ, Richardson B, Douglas T, et al. Virtual violence: Protecting children from Cyberbullying, London, UK. 2009.

- OECD. The protection of children online: risks faced by children online and policies to protect them. OECD Digital Economy Papers, 179: OECD publishing. 2011.

- Livingstone S, Palmer T. Identifying vulnerable children online and what strategies can help them. London, UK: UK Safer Internet Centre. 2012.

- Enck- Wanzer S, Murray S. How to hook a hottie: Teenage boys, hegemonic masculinity and Cosmo girl magazine: In Wannamaker, A. (ed.) Mediated boyhood: boys teens and tweens in popular culture and media. 2010.

- Stone K. Keeping children and young people safe online: balancing risk with opportunity. University of Stirling, UK: With Scotland. 2013.

- Angelides S. Socio-legal and pedagogical responses to the practice of consensual teenage texting. Technology, hormones, and stupidity: The affective politics of teenage sexting. Sexualities. 2013;16: 665-89.

- Doring N. Consensual sexting amongst adolescents: Risk prevention through abstinence education or safer sexting: Cyber psychology. Cyberpsychology. 2014; 8.

- Bryce J, Fraser J. The role of disclosure of personal information in the evaluation of risk and trust in young peoples’ online interactions. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2014; 30: 299-306.

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, et al. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact on secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2008;49: 376-85.

- Walker J, Moak S. Childs play or child pornography: The need for better laws regarding sexting. ACJS Today: Academy of criminal justice sciences. 35; 1-9.

- Millwood Hargrave AM, Livingstone S. Harm and offence in media content: A review of the evidence. Bristol, UK: Intellect. 2009.

- Gorzig A. Who bullies and who is bullied online? A study of 9-16-yearold internet users in 25 European Countries. London, UK: EU Kids Online. 2011.

- Korenis P, Billick SB. Forensic Implications: Adolescent Sexting and Cyberbullying. Psychiatry Quarterly. 2014; 85: 97-101.

- Levin A. Victims find little escape from cyberbullies. Am J Psychiat. 2011;76: 46.

- Munro E. The protection of children online: a brief scoping review to identify vulnerable groups. London, UK: Childhood wellbeing research centre. 2011.

- Svedin CG. Research evidence in to behavioural patterns which lead to becoming a victim of sexual abuse: In Ainsaar M, Loof L (Eds) Online Behaviour related to child sexual abuse: Literature review. EU Safer Internet Project. Risk-taking online behaviour empowerment through research and training. 2011.

- Ybarra M, Espelage D, Mitchell K. The co-occurrence of internet harassment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimisation and perpetration: Association of psychosocial indicators. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41: 31-41.

- Barnardo’s. Cutting them free: How is the UK progressing in protecting its children from sexual exploitation? 2012.

- Jago S, Arocha L, Brodie I, et al. What’s going on to safeguard children and young people from sexual exploitation? Luton: University of Bedfordshire. 2011.

- Scott S, Skidmore P. Reducing the risk: Barnardo’s support for sexually exploited young people. A two-year evaluation. 2016.

- Lerpiniere J, Hawthorn M, Smith I, et al. The sexual exploitation of looked after children in Scotland: A scoping study to inform methodology for inspection. Glasgow: CELCIS. 2013.

- Webb A, Laird C. Child sexual exploitation. Stirling, UK: WithScotland. 2014.

- Hackett S. Children and Young people with harmful sexual behaviours. Totness: Dartington. 2014.

- Papadopoulos L. Sexualisation of young people review: London: The Home Office. 2010.

- Weldon V. Online porn blamed for rise in sexual violence. 2012.

- Virag G, Parti K. Sweet child of our time: Online sexual abuse of children: A research exploration. J open criminology. 2011;4: 81-90.

- Bryce J. Bridging the digital divide: Executive summary. London: Orange and the Cyberspace Research Unit. 2008.

- Davidson J. Online grooming and the targeting of vulnerable children: Findings from the E. C. online groomers study: Paper presented at the fifth international conference: Keeping children and young people safe online: Warsaw, Poland. 2011.

- Scottish Executive. The Protecting Children and Young People: Framework for Standards. Edinburgh, UK: Astron. 2004.

- Ashurst L, McAllinden A. Young people, peer-to-peer grooming and sexual offending: Understanding and responding to harmful sexual behaviour within a social media society. Probation J. 2005;62: 374-88.

- Calvert C. Sex, cell phones, privacy, and the first amendment: When children become child pornographers and the Lolita effect undermines the law. Common Law Conspectus: J Communication Law and Policy. 2009;18: 1-65.

- Corbett D. Let’s talk about sext: The challenge of finding the right legal response to teenage practice of ‘sexting. J Internet L. 2009;13: 3-8.

- McLaughlin JH. Crime and punishment: Teen sexting in context. Pennsylvania State Law Review. 2010;115: 135-7.

- Dake J, Price J, Maziarz L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sexting behaviour in adolescents. Am J of Sex Edu. 2012;7: 1-15.

- Barnardo’s. Puppet on a string: The urgent need to cut children free from sexual exploitation. 2011.

- McAllinden A. Grooming and the sexual abuse of children: Institutional, internet and family dimensions. Clarendon Studies of Criminology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 2012.

- Gillespie A. Adolescents, sexting and human rights. Human Rights Law Review. 2013;13: 623-43.

- Livingstone S. A rationale for positive online content for children. Communication Research Trends. 2009;28: 12-6.

- McCrory E, Walker-Rhymes P. A treatment manual for adolescents displaying sexually harmful behaviour: Change for good. NSPCC, UK: Jessica Kingsley. 2011.

- NSPCC. Premature sexualisation: Understanding the risks. London, UK: NSPCC. 2011.

- NSPCC. Children, Young People and sexting: Summary of a qualitative study. London, UK: NSPCC. 2012.

- Scott S, Skidmore P. Reducing the risk: Barnardo’s support for sexually exploited young people. A two-year evaluation. 2016.

- American Psychological Association. Report of the APA task force on the sexualisation of girls. 2012.

- Ashurst E. Developing and testing a general training model for improving professional practice for case managers: Using practitioners working with young people displaying sexually harmful behaviour for an exemplar. Belfast, UK: Queens University. 2012.

- Bryce J. Cyberpsychology and human factors. IET Engineering and Technology. 2015.

- Bryce J, Klang M. Young people, disclosure of personal information and online privacy: Control, choice and consequences. Information Security Technical. 2009;14: 160-6.

- Byron T. The Byron report: Safer children in a digital world. Nottingham, UK: DSCF Publications. 2008.

- Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Paediatr. 2011;127: 800-4.

- Jewkes Y, Yar M. Handbook of internet crime. London, UK: Routledge. 2011.

- Livingstone S. Regulating the internet in the interests of children: Emerging European and international approaches. In R. Mansell and M. Raboy (eds). The handbook on global media and communication policy. 505-524. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 2011.

- Ofcom. UK Children’s media literacy. Ofcom. 2010.

- Police Scotland. National child abuse investigation into online abuse. 2016.

- UKCCIS/Ofcom. Children and Parents: Media use and attitudesbased on 1717 interviews with children aged 5-15 and their parents. London, UK: Ofcom. 2011.

- Wells M, Mitchell K. How do high risk youth use the internet? Characteristics and implications for prevention. Child maltreatment. 2008;13: 227-34.

- Ybarra M, Espelage D, Mitchell K. The co-occurrence of internet harassment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimisation and perpetration: Association of psychosocial indicators. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41, 31-41.