Statistical Study of HIV Stigma and Discrimination in Northeastern Nigeria Through Statistical Charts

2 Department of Commers & Management Science, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India, Email: narinderp.singh@jimsindia.org

3 Department of Mathematics, Yusuf Maitama Sule University, Kano State, Nigeria, Email: drvvsinghmath@nwu.edu.ng

Received: 18-Feb-2021 Accepted Date: Mar 01, 2021; Published: 09-Mar-2021, DOI: 10.37532/2752-8081.21.5.23

Citation: Chiwa Musa Dalah, VV Singh. Statistical Study of HIV Stigma and Discrimination in Northeastern Nigeria Through Statistical Charts. J Pur Appl Math. 2021; 5(1):10:15.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

The present paper is focused on a study of the stigmatization and discrimination faced by people living with HIV in Northeastern part of Nigeria. Previous research has established that awareness and knowledge of HIV/AIDS in Northeastern Nigeria are high. However, still, stigmatization and discrimination may be experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS. In contrast, HIV discrimination refers to someone’s unfair and unjust treatment based on their real or perceived HIV status. North-Eastern Nigeria consists of six states (6), namely Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, and Yobe states, with a total population of about twenty-five million (25m). The secondary data from the federal ministry of health is used for the assessment and predictions have carryout.

Keywords

HIV, Stigma, Discrimination analysis, Northeastern Nigeria

Introduction

The HIV-related Stigma refers to negative beliefs, feelings, and attitudes towards people living with HIV, their families. Stigma and discrimination associated with HIV relate to racism, derogatory perceptions, and violence towards people living with HIV and AIDS. The people live in rural ar- eas where the level of education is low, the poverty level is high, and culture and tradition may contribute to the epidemic’s spread. The people who work with them (HIV service providers), and members of groups that have been heavily impacted by HIV, such as gay and bisexual men, homeless people, street youth, and mentally ill people. According to UNAIDS (2015, 2017), 35% of countries with available data estimate that more than 50% of individuals report discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV. Stigma and discrimination continue to be faced by those most at risk for HIV (key affected populations) based on their actual or perceived health status, race, socioeconomic status, age, sex, sexual orientation or gender identity, or other reasons. Stigma and discrimination manifest themselves in many ways. Please refer to Stangl, A. L, et al. (2013) for a systematic review of Stigma and discriminatory reduction strategies. Human rights violations may occur in health care settings, restricting people from taking health services or enjoying quality health care. Family, acquaintances, and the broader population are shunned by some people living with HIV, and other primary customers are encouraged. In contrast, others face poor treatment in educational and work settings, erosion of their rights, and psychological damage [1-5].

The Stigma Index of People Living with HIV records the experiences of people living with HIV. As of 2015, the HIV Stigma Index was being used by more than 70 countries, or more than 1,400 persons living with HIV were trained as interviewers, and more than 70,000 people with HIV were interviewed. Huffington (2012) statistics, which were obtained from 50 countries in 2017, suggest that approximately Stigma and discrimination also make individuals vulnerable to precautionary guidelines for HIV. One of the eight people living with HIV is denied health services due to Stigma and racism. Fear of Stigma and prejudice is the key reason people are reluctant to get screened, reveal their HIV status, and prescribe antiretroviral drugs, referring to UNAIDS research (2016, 2017) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (2011, 2015) (ARVs). One analysis from the Well project (2016) found that respondents with elevated prejudice levels were more than four significantly more likely to report inadequate care access. The leads to the rise of the global HIV epidemic and a higher number of deaths associated with AIDS. A reluctance to take an HIV test means that more people are diagnosed late when the infection may have already escalated to AIDS. The treatment less effective, increasing the likelihood of transmitting HIV to others and causing early death [6-10].

In the United Kingdom (UK), many individuals diagnosed with HIV are diagnosed at a late stage of infection, defined as a CD4 count below 350 within three months of diagnosis, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) report (2015). Although the late diagnosis of HIV in the UK declines from 56% in 2005 to 39% in 2015, this figure remains unacceptably high.

The PLHIV Stigma Index (2015) in South Africa discusses the Stigma that prevented many young women from participating in an HIV prevention trial using vaginal gels and pills to help them remain HIV-free. Many indicated that they could be afraid that using these products would trigger them to be wrongly considered as having HIV. Furthermore, the fear of isolation and persecution were known as living with HIV will lead them to adapt to activities that placed them at higher risk of getting the virus. The epidemic of fear, marginalization, and oppression has weakened individuals, societies, and societies’ willingness to support themselves and provide support and encouragement to those affected. The initiatives to curb the infection, in no small way, hinder us. It complicates testing decisions, status disclosure, and the opportunity to share preventive activities, including family planning resources.

Forms of HIV stigma and discrimination

The stigma associated with HIV and AIDS can lead to discrimination; for example, when it is prohibited for people living with HIV to travel, utilize healthcare facilities, or seek employment.

Self-stigma/internalized stigma: Self-stigma, or internalized Stigma, has an equally damaging effect on the mental wellbeing of people living with HIV or from key affected populations. To seek support and medical treatment, fear of prejudice breaks down confidence. Self-stigma and fear of a negative community response will inhibit ways to overcome the HIV epidemic by maintaining the wall of silence and shame surrounding the virus. A significant but neglected aspect of living with HIV is negative self-judgment that results in shame, worthlessness, and blame. Self-stigma has impacted a person’s ability to live positively, limits meaningful self-agency, quality of life, treatment adherence, and access to health services. In Zimbabwe, ZNNP+ and Trcaire designed, implemented, and evaluated a 12-week pilot program to support people living with HIV to work through self- stigmatizing beliefs. After twelve weeks, participants reported profound shifts in their lives. A decrease in self-stigma, depression (78 percent) and fears about disclosure (52%), and increased feelings of satisfaction (52%) and daily activity were reported by the majority of participants (61%, (70%). Evidence suggests that individuals from key populations affected are also disproportionately targeted by self-stigma. A study in China who has sex with men, for example, found that depression experienced by participants due to feelings of self-stigma around homosexuality directly affected HIV permeability testing.

Similarly, a study in Tijuana, Mexico, which has sex with men found that self-stigma, was strongly associated with never having tested for HIV. In contrast, testing for HIV was associated with identifying as homosexual or gay and being more ’out’ about having sex with men. In countries that are hostile to men who have sex with men and other key populations, innovative strategies are needed to engage individuals in HIV testing and care programs without exacerbating stigma and discrimination experiences.

Governmental Stigma: The discriminatory HIV laws, policies, and regulations of a country can alienate and exclude people living with HIV, strengthening the Stigma of HIV and AIDS. In 2014, 64% reporting to UNAIDS had regulations to protect discrimination against people living with HIV. In contrast, 72 countries have HIV-specific laws that prosecute individuals living with HIV for various crimes. Criminalization of key affected populations remains widespread, with 60% of countries reporting legislation, regulations, or policies that present barriers to the provision, treatment, care, and support of effective HIV prevention. As of 2016, 73 countries criminalized same-sex activity, and injecting drugs use is widely criminalized, leading to high incarceration levels among people who use drugs. More than 100 countries criminalize sex work or aspects of sex work. Even in countries where sex work is at least partially legal, the law rarely protects sex workers. Many are at risk of discrimination from both state and non-state actors, such as government agencies, partners, families, clients, and some abuse and violence. For example, some 15,000 sex workers in China were detained in so-called custody and education centers in 2013. Laws that criminalize HIV non-disclosure, exposure, and transmission perpetuate Stigma and deter people from HIV testing, and put the responsibility of HIV prevention solely on the partner living with HIV. In May 2015, the Australian state of Victoria repealed the country’s only HIV-specific law criminalizing the intentional transmission of HIV. The repealed law - Section 19A of the Crimes Act 1958 - carried a maximum penalty of 25 years imprisonment, even more than the maximum for manslaughter (which is 20 years). The legislation to repeal the law was developed by collaborating with several stakeholders, including legal, public health, human rights experts, and representatives of people living with HIV. It was seen as a major step forward for the rights of people living with HIV.

Restrictions on entry travel and stay: As of September 2015, 35 countries have laws restricting the entry, stay, and residence of people living with HIV. In 2015, Lithuania became the most recent country to remove such restrictions. As of 2015, 17 countries will deport individuals once their HIV-positive status is discovered. Five have a complete entry ban on people living with HIV, and four require a person to prove they are HIV negative before being granted entry. Deportation of people living with HIV has potentially life-threatening consequences if they have been taking HIV treatment and are deported to a country that has limited treatment provision. Alternatively, people living with HIV may face deportation to a country where they would be subject to even further discrimination - a practice that could contravene international human rights law.

Healthcare stigma: Healthcare professionals can medically assist someone infected or affected by HIV and provide life-saving information on preventing it. However, HIV-related discrimination in healthcare remains an issue and is particularly prevalent in some countries. It can take many forms, including mandatory HIV testing without consent or appropriate counseling. Health providers may minimize contact with, or care of patients living with HIV, delay or deny treatment, demand additional payment for services, and isolate people living with HIV from other patients. For women living with HIV, denial of sexual and reproductive health and rights services can be devastating. For example, 37.7% of women living with HIV surveyed in 2012 in a six-country study in the Asia Pacific region reported being subjected to involuntary sterilization. Healthcare workers may violate a patient’s privacy and confidentiality, including disclosing their HIV status to family members or hospital employees without authorization. Studies by WHO in India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand found that 34% of respondents reported breaches of confidentiality by health workers. People from key affected populations may face additional discrimination in health- care settings. Health providers’ discriminatory attitudes may also lead them to judge a person’s HIV status, behavior, sexual orientation, or gender identity, leading individuals to be treated with- out respect or dignity. These views are often fueled by ignorance about HIV transmission routes among healthcare professionals. In 2012, half of all people living with HIV in Thailand started treatment very late and had CD4 counts under 100. HIV stigma was identified as started to service uptake, so health authorities set a target to cut HIV-related Stigma and discrimination by 50% by 201,6. The Ministry of Public Health found that over 80% of healthcare workers had at least one negative attitude to HIV. In comparison, roughly 20% knew colleagues who were unwilling to provide services to people living. In comparison, or provided them substandard services. More than half of respondents reported using extreme personal protection measures such as wearing gloves when interacting with people with extreme HIV, 25% of people living with HIV surveyed said that they avoided seeking healthcare for fear of disclosure or poor treatment, while a third had their status disclosed without their consent. In response to these findings, the Ministry of Public Health collaborated with civil society and international partners and developed initiatives to sense collaborate doctors in clinical and non-clinical settings. Early results in 2014 indicated that improving healthcare workers’ attitudes doesn’t just improve care for people living with HIV, but healthcare workers’ attitudes are seen as role models. As of 2017, Thailand had collected data from 22 provinces. The Thai Ministry of Public Health is rolling out an accelerated system-wide stigma reduction program in collaboration with civil society and concerned communities.

A study of health providers in program facilities in India found 5580% of providers displayed a willingness to prohibit women living with HIV from having children, endorsed mandatory testing for female sex workers (9497%), and stated that people who acquired HIV through sex or drugs (5083%). These experiences may leave people living with HIV and people from key affected populations too afraid to seek out healthcare services or be prevented from accessing them for instance, if a nurse refuses to treat a sex worker after finding out about their occupation. It prevents many people from key affected populations from being honest with healthcare workers if they’re a sex worker, has same-sex relations, or inject drugs, meaning they are less likely to get from services that could help them [11-15].

Employment stigma. In the workplace, people living with HIV may suffer Stigma from their co- workers and employers, such as social isolation and ridicule, or experience discriminatory practices, such as termination or refusal of employment. Evidence from the People Living with HIV Stigma Index suggests that, in many countries, HIV-related stigma and employment refusal as frequently or, more frequently, a cause of unemployment or denial of work opportunity as ill-health. Key findings from people living with HIV in nine countries across four regions in 2012 found that as a result of their HIV still-healthy 8% (Estonia) and 45% (Nigeria) of respondents had lost their job or source of income; between 5% (Mexico) and 27% (Nigeria) were refused the opportunity to work, and between 4% (Estonia) and 28% (Kenya) had the nature of their work changed or had been refused promotion. Besides, 8% of respondents in Estonia to 54% in Malaysia reported discriminatory reactions from employers once they were aware that besides states Estonia responds Entsonia to 54% in Malaysia reported discriminatory reactions from co-workers who became aware of their colleague’s HIV status. It is always in the back of your mind if I get a job, should I tell my employer about my HIV status? There is a fear of how they will react to it. It may cost you your job. It may make you so uncomfortable it changes relationships. Yet you would want to be able to explain why you are absent, and going to the doctors. By reducing Stigma in the workplace (via HIV and AIDS education, offering HIV testing, attributing towards the cost of ARVs) employees are less likely to take days off work and be more productive in their jobs. It ensures people living with HIV can continue working.

Community and household level stigma. Community-level Stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV can force people to leave their homes and change their daily activities. In many contexts, women and girls often fear Stigma and rejection from their families. Only become homes, they stand to lose their social place of belonging and because they could lose their shelter, their children, and their ability to survive. The isolation that social rejection brings can lead to low self-esteem, depression, and even thoughts or acts of suicide. The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) reports that in Bangladesh more than half of women living with HIV have experienced Stigma from a friend or neighbor and one in five feel suicidal. In the Dominican Republic, six out of ten women living with HIV fear being the subject of gossip, neighbor, Ethiopia, more than half of all women living with HIV report having low self-esteem. They [my family] were embarrassed and didn’t want to talk to me. My mother essentially said, Good luck, you’re on your own. - Shana Cozad from Tulsa, USA, on her family’s reaction after she tested positive for HIV. A survey of married HIV-positive women (1529 years) in India found 88% of respondents experienced Stigma and discrimination from their family and community. Women with older husbands and households with lower economic status were significantly more likely to experience Stigma and dis- crimination from their husbands’ family and friends, and neighbors. Stigma and discrimination can also take particular forms within community groups such as key affected populations. For example, studies have shown that within some lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) communities, there is segregation between HIV-positive and HIV-negative people, where people associate predominately with those of the same status.

Ending HIV stigma and discrimination. To end HIV stigma and discrimination is very necessary so that people living with HIV/AIDS can feel free within the community. The use of specific programs that emphasize people’s rights for living with HIV is a well-documented way of eradicating Stigma. As well as being made aware of their rights, people living with HIV can be empowered to take action if these rights are violated. Ultimately, adopting a human rights approach to HIV and AIDS is in the public’s interest. Stigma blocks access to HIV testing and treatment services, making onwards transmission more likely. The removal of barriers to these services is key to ending the global HIV epidemic. In March 2016, UNAIDS and WHO’s Global Health Workforce Alliance launched the Agenda for Zero Discrimination in Healthcare. The works towards a world where everyone, everywhere, can receive the healthcare they need with no discrimination, in line with The UN Political Declaration on Ending AIDS. Zero discrimination is also at the heart of the UN- AIDS vision and one of its fast-Track response targets. The focuses on addressing discrimination in healthcare, workplace, and education settings. Although Ghana’s Constitution protects all citizens from discrimination in employment, education, and housing and ensures their right to privacy, there is ambiguity in how these provisions apply to people living with HIV and to key affected populations.

Methodology of Analysis

Utilizing text descriptions is one of the most common ways of presenting numerical data, known as a textual presentation of data. This approach is characterized used by official agencies. People with a literary bent who hate the drabness of a table would enjoy the textual form of data presentation. Researchers prefer the presentation of data in the form of a table because the table can be built in such a way that it can contain a significant amount of data in a succinct format.

Treating the advantage of tabular data presentation over textual data presented in this study, secondary data from the Federal Ministry of health survey on NARSHS Plus carried out in 2012 were used. The data are tabulated according to various parameters and reasons/ facts, which need analysis. The results are presented in tables and charts for easy understanding.

Main Results

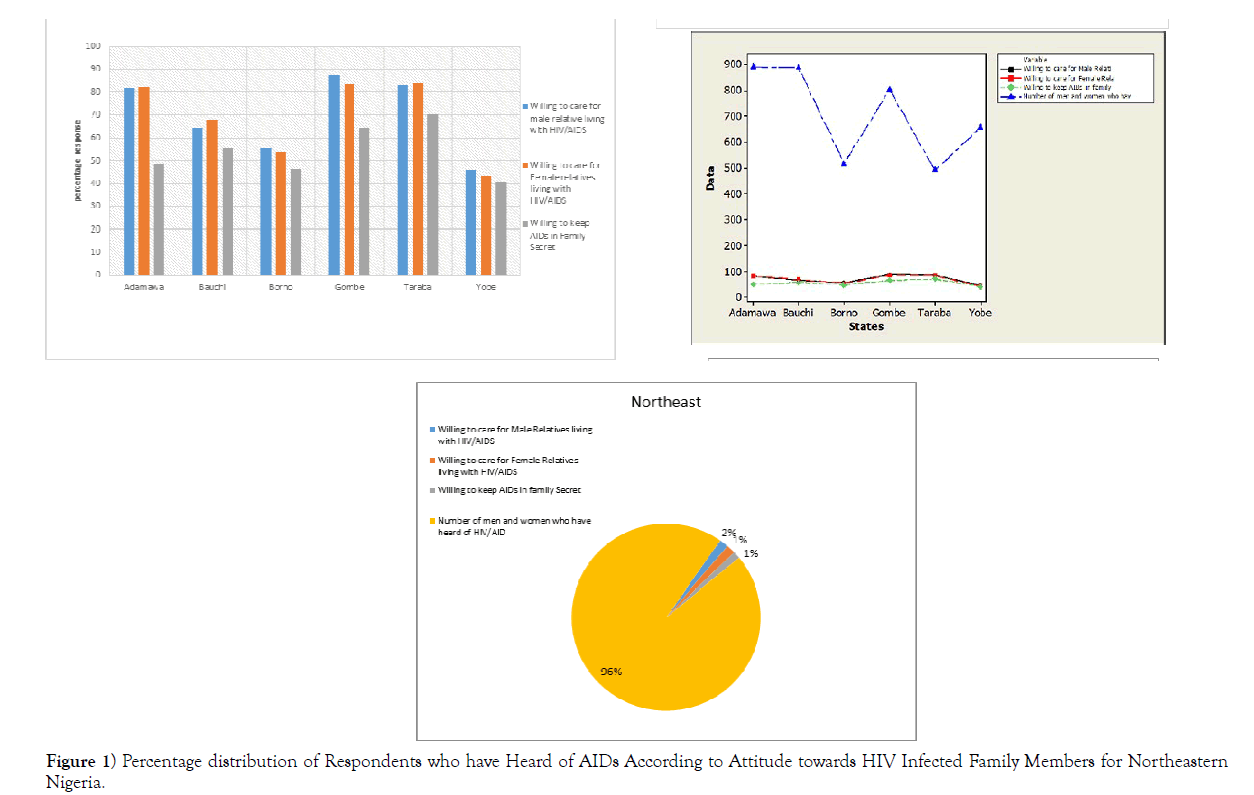

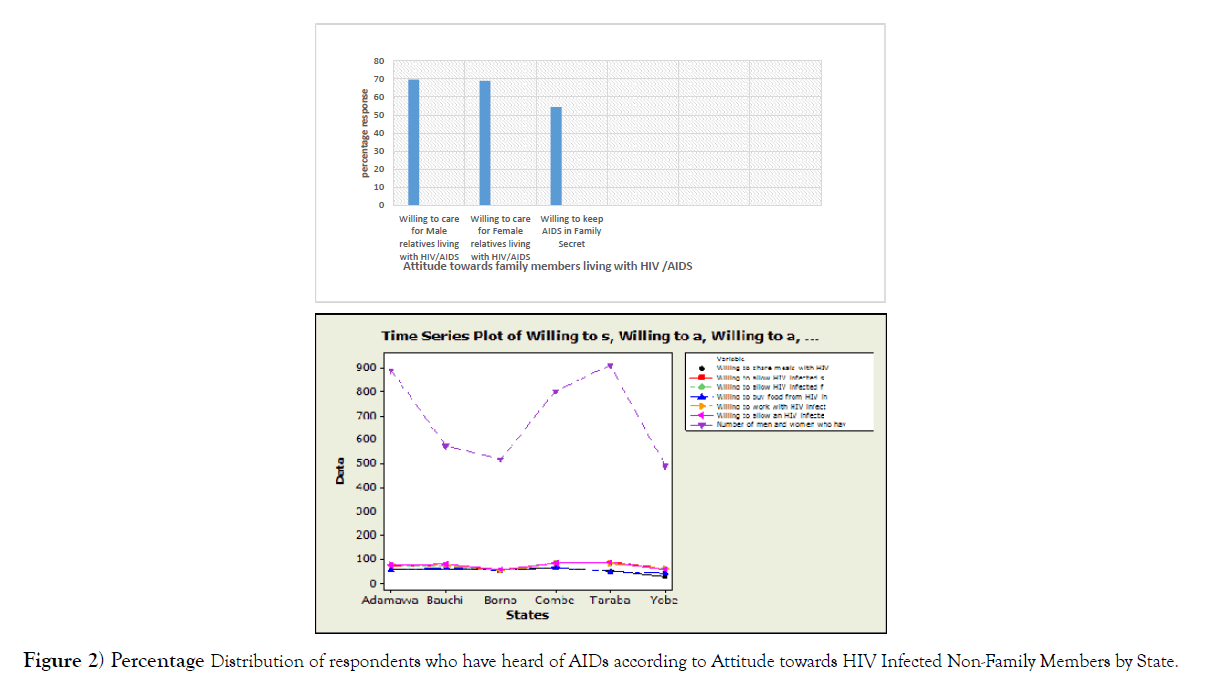

From (Table 1) and (Figure 1), it is clear that the attitude of people towards family members who have been infected with HIV/AIDS is positively high in most of the states in Northeastern Nigeria, with few states having less than fifty percent (50%). Male (Table 2) and (Figure 2) have shown that people’s attitude to family members who have been infected with HIV/AIDS is generally high in Northeastern Nigeria.

| S/N | State | Willing to care for Male Relatives living with HIV/AIDS |

Willing to care for Female Relatives living with HIV/AIDS |

Willing to keep AIDs in family Secret | Number of men and Women who have Heard of HIV/AID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adamawa | 81.5 | 81.9 | 48.6 | 891 |

| 2 | Bauchi | 64.5 | 67.8 | 56.0 | 887 |

| 3 | Borno | 55.5 | 53.9 | 46.4 | 516 |

| 4 | Gombe | 87.6 | 83.3 | 64.6 | 803 |

| 5 | Taraba | 83.2 | 83.6 | 70.5 | 491 |

| 6 | Yobe | 46.0 | 43.0 | 40.7 | 657 |

| Average | 69.7 | 68.9 | 54.5 | 707.5 |

Table 1 Attitude towards Family Members Living with HIV/AIDs Percentage distribution of Respondents, Attitude towards HIV Infected Family Members by State; FMoH, Nigeria,2012.

Figure 1) Percentage distribution of Respondents who have Heard of AIDs According to Attitude towards HIV Infected Family Members for Northeastern Nigeria.

| Region | Willing to care for Male Relatives living with HIV/AIDS |

Willing to care for Female Relatives living with HIV/AIDS |

Willing to keep AIDs in family secret |

Number of men and women who have heard of HIV/AIDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 69.7 | 68.9 | 54.4 | 707.5 |

Table 2 Attitude towards Family Members Living with HIV/AIDS Percentage distribution of Respondents Attitude towards HIV Infected Family Members for Northeastern Nigeria; FMoH, Nigeria, 2012.

Figure 2) Percentage Distribution of respondents who have heard of AIDs according to Attitude towards HIV Infected Non-Family Members by State.

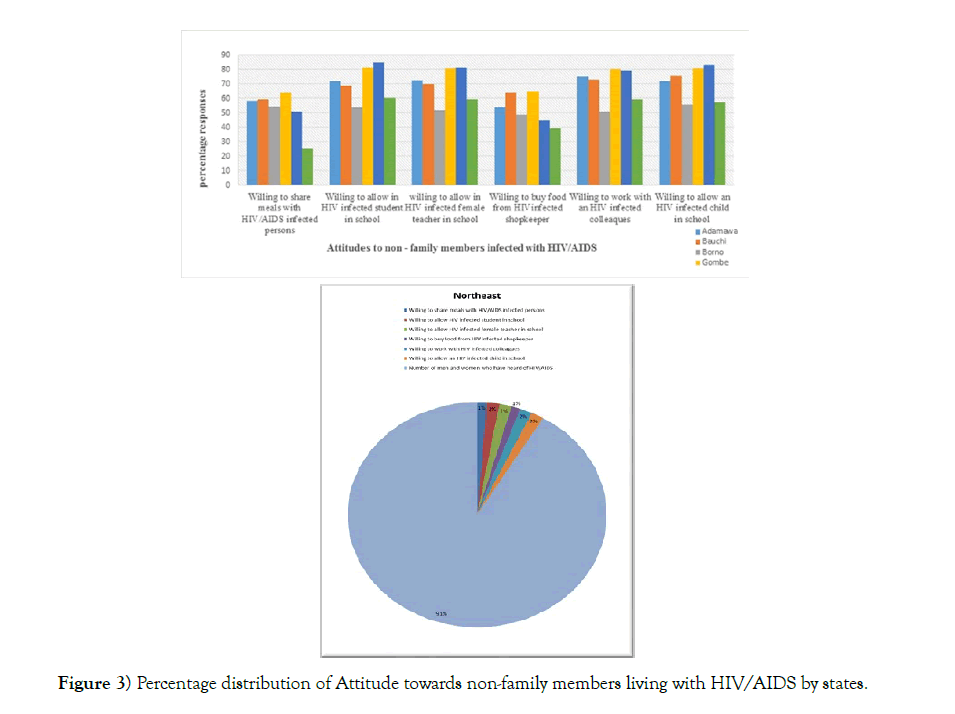

(Table 3) and (Figure 3) show that the attitude to non-family members infected by HIV is positively high in most of the region’s states, over 50%.

| S/N | State | Willing to share meals with HIV infected persons |

Willing to allow HIV infected student in school |

Willing to allow HIV infected female teacher school |

Willing to buy food from HIV infected shopkeeper |

Willing to work with HIV infected colleagues school |

Willing to allow an HIV infected child in |

Number of men and women who have heard of HIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adamawa | 58.6 | 71.8 | 72.4 | 54.0 | 75.5 | 72.1 | 891 |

| 2 | Bauchi | 59.2 | 69.0 | 70.0 | 64.1 | 72.9 | 76.0 | 574 |

| 3 | Borno | 54.6 | 53.8 | 52.0 | 48.8 | 50.9 | 56.1 | 516 |

| 4 | Gombe | 63.9 | 81.3 | 81.0 | 65.1 | 80.4 | 80.8 | 803 |

| 5 | Taraba | 50.9 | 85.1 | 81.5 | 45.0 | 79.4 | 83.2 | 910 |

| 6 | Yobe | 25.5 | 60.5 | 59.5 | 39.5 | 59.6 | 57.3 | 490 |

| Av % | 56.1 | 70.3 | 69.4 | 52.8 | 69.8 | 70.9 | 697.30 |

Table 3 Attitude Towards non -Family Persons Living with HIV/AIDsPercentage distribution of respondents who have heard of AIDs According to Attitude towards HIV Infected Family Members by State; FMoH, Nigeria, 2012.

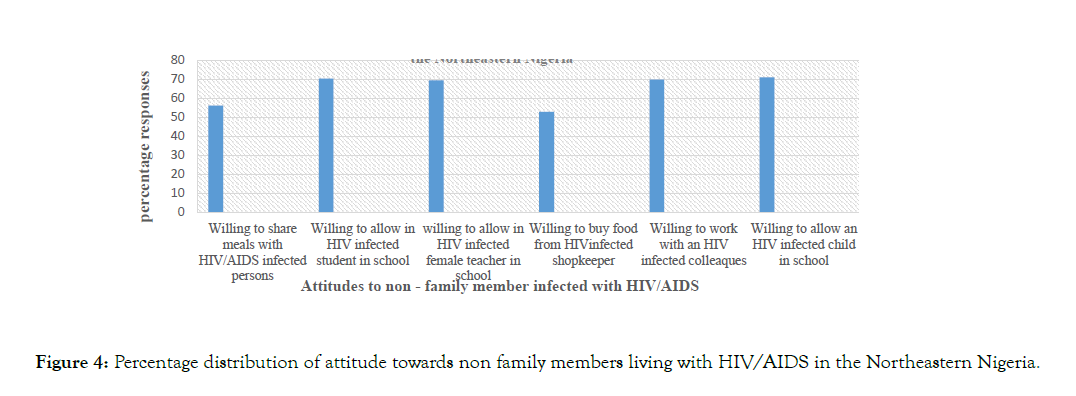

(Table 4) and (Figure 4) show that the attitude to non-family members infected by HIV is positively high in most of the region’s states, over 50%.

| S/N | Region | Willing to share meals with HIV/AIDS infected persons |

Willing to allow HIV infected student in school | Willing to allow HIV infected female teacher in school |

Willing to buy food from HIV infected shopkeeper | Willing to work with HIV infected colleagues |

willing to allow an HIV infected child in school |

Number of men and women who have heard of HIV/AIDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 56.1 | 70.3 | 69.4 | 52.8 | 69.8 | 70.9 | 697.3 |

Table 4 Attitude Towards non -family members Living with HIV/AIDs Percentage Distribution of Respondents who have Heard of AIDs According to Attitude towards HIV Infected Non-Family Membersin Northeastern Nigeria; FMoH, Nigeria, 2012.

Conclusion Remarks and Future Predictions

In March 2016, UNAIDS and WHO’s Global Health Workforce Alliance launched the agenda for zero discrimination in healthcare. The works towards a world where everyone, everywhere, can receive the healthcare they need with no discrimination, in line with the United Nations political declaration on ending AIDS. Zero discrimination is also at the heart of the UNAIDS vision and one of its fast-track response targets. The focuses on addressing discrimination in healthcare, workplace, and education settings. The present analysis is done to finds that the people’s attitude to family members and non-family members infected with HIV/AIDS is positively high among people of Northeastern Nigeria. Virtually all the analysis variables were significantly associated with positive attitudes to people living with HIV/AIDS, as shown in Tables 1 & 2 and the corresponding figures presented in charts and pictorial charts. The relevant data presentation predicts that most of the people are ready and willing to associate with people infected by HIV/AIDS.

The analysis has shown that people living with HIV/AIDS in Northeastern are positively high, but much more needs to be done to end HIV stigma and discrimination. These can include the use of specific programs that emphasize the rights of people living with HIV, well-documented ways of eradicating Stigma and being made aware of their rights. People living with HIV can be empowered to take action if these rights are violated. Ultimately, adopting a human rights approach to HIV and AIDS is in the public’s interest. Stigma blocks access to HIV testing and treatment services, making onwards transmission more likely. The removal of barriers to these services is key to ending the global HIV epidemic.

REFERENCES

- UNAIDS J. oH. On the Fast-Track to end AIDS by 2030: Focus on location and population. Technical report. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2015.

- UNAIDS J. Agenda for zero discrimination in health-care settings. media asset /20170720 Data book ; 2017.

- Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, et al. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV‐related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come?. J Int AIDS Society. 2013;16:18734.

- Michel Sidibe.Giving Power to Couples to End the AIDS Epidemic. A Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.2012

- UNAIDS J.Ghanaaddressing the barrier of stigma and discrimination for women.Strategy 2016.

- UNAIDS J. HIV prevention among key populations Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations 2016.

- UNAIDs U, World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: progress report 2011. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: progress report 2011.. 2011.

- Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, et al. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(10):1101.

- Chau C, Kirwan P, Brown A, Gill N, Delpech V. HIV diagnoses, late diagnoses and numbers accessing treatment and care. 2016 report. London: Public Health England. 2016.

- Chinyere Fidelia Nnajiofor. Stigma and Discrimination Against Women Living with HIV, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. World Health Organization; 2015.

- Index PS. We are the change. Dealing with self-stigma and HIV/AIDS: An experience from Zimbabwe.

- Wei C, Cheung DH, Yan H, Li J, Shi LE, Raymond HF. The impact of homophobia and HIV stigma on HIV testing uptake among Chinese men who have sex with men: a mediation analysis. J Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999). 2016 ;71(1):87.

- Dalah CM, Singh VV. A Survey and Assessment Report of Hiv/Aids Awareness of in North-Eastern Nigeria. International Journals of Advanced Research in Computer Science and Software Engineering, ISSN. 2017:105-12.

- Chiwa MD, Singh VV, Mohamad AE. Statistical survey on awareness of Hiv/Aids and its impact on economic development in northern Nigeria during the period 2010-2015. J Statistical Econometric Methods. 2018;7(3):35-62.