Surgical treatment of peripheral ossifying fibroma: clinical and histopathological aspects. A case report

2 Senior Lecturer, Periodontics. NSVK Sri Venkateshwara Dental College and Hospital, Bangalore 560083, Karnataka, India

Received: 03-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. puldcr-22-5319; Editor assigned: 05-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. puldcr-22-5319 (PQ); Accepted Date: Jul 26, 2022; Reviewed: 20-Jul-2022 QC No. puldcr-22-5319 (Q); Revised: 23-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. puldcr-22-5319 (R); Published: 27-Jul-2022, DOI: 10.37532. puldcr-22.6.4.4-7

Citation: Srinivasan P, Durgesh P. Surgical treatment of peripheral ossifying fibroma: clinical and histopathological aspects. A case report . Dentist Case Rep. 2022;6(4):04-07

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is an infrequently occurring, slowly progressing, innocuous, nodular overgrowth of the gingiva, which belongs to the category of the “reactive lesions of the gingiva.” There are several such overgrowths with similar clinical manifestations, but diverse etiology and histopathological features, thus presenting a challenge for the clinician. Through anamnesis, clinical, radiographic and histopathological analysis helps to establish the diagnosis which is key to the successful management of such lesions. This article describes a case of POF in a 43-year-old male patient. The scientific data pertaining to the clinical, radiographic, histologic features, aggressive treatment strategies, relapse and close follow-up of POF are discussed in detail. The article also stresses on the importance of differential diagnosis.

Key Words

Epulides; nodular overgrowth; Reactive lesions of gingiva; Peripheral ossifying fibroma

Introduction

Increase in the size of the gingiva, termed “gingival overgrowth” is one of the attributes of gingival disease. They can be designated and classified based on their etiology, pathogenesis, site, distribution, and degree of enlargement [1]. Traditionally, localized gingival overgrowths have been termed “epulides,” a term used to describe sessile or pedunculated swellings of the gingiva. Since the term “epulides” does not seem to offer any histologic description of a specific lesion, it is only appropriate that the term, “reactive lesions of the gingiva” be used instead to describe such lesions [2].

The features common to epulides that distinguish them clinically from the plaque-induced inflammatory enlargements are summarized in (Table 1).

Table 1 Common Features of Epulides

| Source of Origin and development. | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Derived from the periodontal ligament ( PDL). | Reactive lesion |

| Develop from under the free gingival margin | Not primarily plaque-related |

| High growth and recurrence rate | |

| They require specific management |

The lesions which fall under the category of reactive lesions of the gingiva are the fibrous epulis/peripheral fibroma, pyogenic granuloma/ angiogranuloma, and peripheral giant cell granuloma [2,3].

Peripheral Fibroma

This lesson is the most common of the epulides representing the prototype, occurring in adults with a female sex predilection. It is essentially a “reactive fibrous hyperplasia,” and appears as a firm, pink, uninflamed mass growing from under the gingival margin or interdental papilla. The lesion is generally painless unless traumatized during toothbrushing, flossing, or eating [4]. Histologically, these lesions may show additional foci of calcification (peripheral calcifying fibroma), foci of cementless (peripheral cementifying fibroma), or trabeculae of bone (peripheral ossifying fibroma).

The term peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) was coined by Gardner in 1982. He described POF as a lesion that is reactive in nature and it is not the extraosseous counterpart of the central ossifying fibroma of the maxilla and the mandible [5]. Gingival overgrowths, particularly those belonging to the reactive group are often encountered in clinical practice.

The purpose of this article is to present a case of peripheral ossifying fibroma, briefly review the current literature pertaining to this lesion and underscore the importance of the differential diagnosis of such lesions, which is a key factor in their management. Given the high recurrence rate of this lesion, close follow-up is imperative.

Case Report

A 43-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Periodontics, NSVK, Sri Venkateshwara Dental College, with the chief complaint of “a painless growth of the gums behind his upper front teeth.” The growth started as a small nodule a year ago. It increased in size gradually and attained the present size. The medical history was non-contributory and there was no history of trauma.

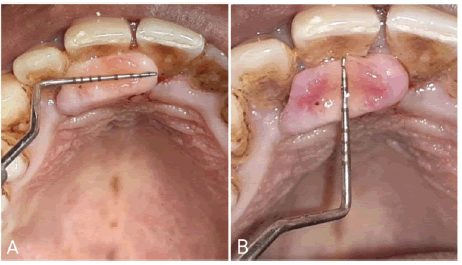

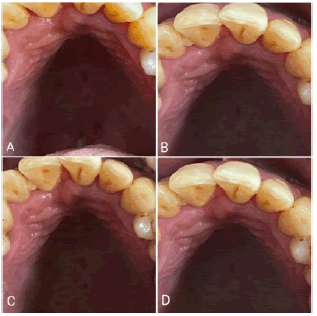

Intra-oral examination revealed a focal smooth-surfaced growth on the palatal aspect of 11 and 12 (Figure 1). The growth measured about 1.5 cm X 0.5 cm (LXB) approximately. It was flat, oval-shaped, and pale pink in color with an intact surface epithelium. On palpation, the growth was non-tender, firm, rubbery in consistency, and sessile in nature with a broad base.

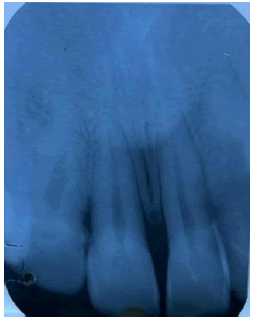

Intraoral periapical radiographs in regions 11 and 12 revealed no pathological findings pertaining to the growth (Figure 2).

Based on the anamnesis, clinical and radiographic examination, the lesion was provisionally diagnosed as Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma.

Treatment

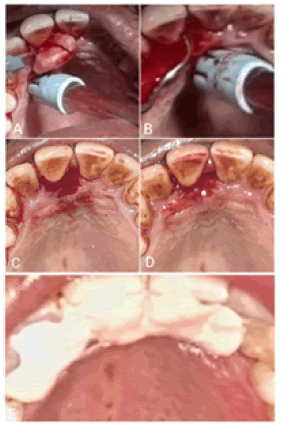

After administering nerve block local anesthesia, the growth was excised in toto at the base using a No.15 BP blade, and the adjacent tissues i.e., the PDL and the periosteum were thoroughly curetted. Scaling and root planing were done to remove all the irritants (Figure 3). The periodontal dressing was placed, postoperative instructions were given to the patient and he was told to report after 7 days. The excised specimen was placed in 10% formalin and sent for histopathological examination.

Histopathology

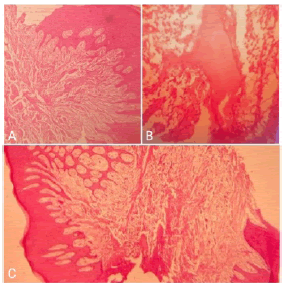

Microscopic examination of H&E stained soft tissue section revealed ulcerated hyperplastic stratified squamous epithelium. The ulcerated area was covered by a fibro purulent membrane. Connective tissue showed plump fibroblasts intermingled with the fibrillar stroma. Few blood vessels lined by endothelial cells were visible. Calcifications in the form of osteoid were detected (Figure 4). The histopathologic report was suggestive of Peripheral ossifying fibroma.

Follow-Up

The patient presented for the 1-week postoperative check-up. The surgical site had healed satisfactorily. Oral hygiene instructions were reiterated to the patient. The 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months follow-up visits showed no evidence of recurrence. The patient was informed about the high recurrence rate, motivated to maintain good oral hygiene, and instructed to return if he noticed any changes (Figure 5).

Discussion

Time and again, it is not uncommon for a clinician to come across several patients with localized, discrete gingival overgrowths, specifically belonging to the category of “reactive lesions of the gingiva.” Amongst these lesions, Peripheral ossifying fibroma is an infrequently occurring focal, reactive benign tumor-like growth of the soft tissue that principally arises from the interdental papilla [6].

The nomenclature related to POF has been a serious bone of contention for a long time. A plethora of terms have been used such as ossifying fibroepithelial polyp, peripheral fibroma with calcification, peripheral cementoossifying fibroma, peripheral cementifying fibroma, and peripheral fibroma with osteogenesis, all adding to the perplexity. Shepherd (1844) reported POF as “alveolar exostosis” [7]. Menzel 1872 first described the ossifying fibroma and in 1927 Montgomery assigned it terminology [8]. The incidence of POF is in the range of 9%-10% [9]. Owing to the influence of the sex hormones, POF is preponderant in females and commonly occurs in the first and second decades of life, and the incidence declines after the third decade [10]. In the present case, however, it was reported in a 43-year-old male patient. The most common location of this growth is in the anterior maxilla with 50%-60% occurrence in the incisor-cuspid region [3]. The size of the POF is generally less than 2 cm in diameter [11]. However, the size may vary and can range from 0.2 cm to 3 cm [11,12]. However, Poon CK reported a case of POF measuring as large as 9 cm in diameter [13]. Another case of large POF with extensive involvement in the anterior portion of the mandible causing displacement of the mandibular anterior teeth was described by Mariano RC et al. [14]. Ossifying fibroma is a slowly growing lesion and it may be present in the oral cavity for several months to years before interfering with function and ulceration of the surface of the growth causes discomfort to the patient [6,16]. A case of extensive POF with a 10- year history of progression was described by Mariano RC et al. [14-15].

The etiopathogenesis of POF is ambiguous and two theories have been proposed in an attempt to shed light on the same. The first theory states that POF is a maturation of the pyogenic granuloma and the second states that it originates from inflammatory hyperplasia of the periodontal ligament. The proximity of the gingiva to the PDL explains the reason for this lesion to be exclusively associated with the gingiva and it frequently arises from the interdental papilla. The presence of oxytalan fibers within the mineralized matrix of some lesions also points to the PDL as the source of origin of POF. [16-19] Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact etiology, several predisposing factors such as trauma to the gingiva, accumulation of plaque and calculus, masticatory forces, ill-fitting appliances, fractured teeth, poor quality or broken down restorations and crowns all play a role in the development of the lesion [5]. Kendrick F stated that POF may arise as a result of the chronic irritation of the periosteal and periodontal membrane causing metaplasia of the connective tissue along with the formation of bone or dystrophic calcified masses [20]. The histopathologic report of our case also demonstrated calcifications in the form of osteoid in the connective tissue.

The radiographic changes associated with POF may range from no deviations from normal to destructive alterations depending on the duration of the lesion. Kendrick F reported that in certain cases, radiographic changes like superficial erosion of the underlying bone, cupping defect, and focal areas of radiopaque calcifications at the center of the lesion can be appreciated [20]. According to Gardner DG and Moon et al., the majority of the POF lesions are generally small and they do not require imaging beyond radiographs [5,21]. Histologically, POF appears to be a non-encapsulated mass of cellular fibroblastic connective tissue of mesenchymal origin covered with stratified squamous epithelium, which is ulcerated in 23%-66% of cases [15,22]. POF is composed of cellular fibrous tissue with areas of fibrovascular tissue that comprise a large number of plump, proliferating fibroblasts intermingling throughout the delicate fibrillar stroma [21]. Batsakis JG and Passos M reported that as the lesions mature, the cellular content of the stroma decreases, and the osseous tissue increases [23,24]. The ossification seen in the cellular stroma demonstrates considerable variation both in qualitative and quantitative aspects. Several forms of calcification ranging from single or multiple interconnecting trabeculae of bone or osteoid either mature lamellar bone or immature cellular bone, less commonly globules of calcified material resembling acellular cementum or a dense diffuse granular dystrophic calcification have been observed [23].

Most of the above-mentioned findings were reported in the histopathopathological analysis of our case as well.

The treatment of POF entails complete excision of the lesion including the PDL and the involved periosteum [16,23,25,26]. Marcos JAG and MartinsJunior JD reported that the relapse rate of PF is considerably high and is in the range of 8%-20% [27,28]. This can be attributed to the incomplete elimination of the lesion and the local irritants [29]. Hence it is imperative to not only excise the lesion completely but also thoroughly eliminate the irritants followed by aggressive curettage of the PDL and the affected periosteum. We have adhered to the same treatment protocol for our case. Farquhar T has stressed the importance of post-operative follow-up to detect early relapse of the lesion, since 1 out of each 5 lesions relapse after excision as reported by Walters JD et al. [30-31].

In consideration of the above-mentioned data, for our case, we have reported the 1month, 3months, and 6months follow-up visits. There were no signs of recurrence of the lesion.

Differential Diagnosis

Any nodular growth on the gingiva necessitates a thorough anamnesis, clinical and radiographic examination followed by histopathological analysis. There are several focal overgrowths of the gingiva which have similar clinical features. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of such lesions becomes mandatory and it includes pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, peripheral ossifying fibroma, irritation fibroma, peripheral odontogenic fibroma, and metastatic cancer [3,7,12,16].

Conclusion

Nodular overgrowths of the gingiva are routinely encountered in clinical practice. POF is a slowly-growing, benign, asymptomatic lesion that will be present in the oral cavity for a long time before the patient seeks care. Although etiopathogenesis is an enigma, the lesion is believed to arise from the cells of the PDL. Treatment involves complete excision of the lesion with aggressive curettage of the PDL and the surrounding periosteum of the bone and complete removal of all the irritants. Histopathological findings are confirmatory and help to establish the correct diagnosis. Close postoperative follow-up is imperative to prevent recurrence of the lesion.

References

- Agrawal AA. Gingival enlargements: Differential diagnosis and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2015;3 (9):779-788. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kfir Y, Buchner A, Hansen LS. Reactive lesions of the gingiva: a clinicopathological study of 741 cases. J Periodontol. 1980;51(11):655-61. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Zhang W, Chen Y, An Z, et al. Reactive gingival lesions: a retrospective study of 2,439 cases. Quintessence Int. 2007;38(2). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- NW Savage, CG Daly. Gingival enlargements and localized gingival overgrowths. Australian Dental Journal 2010; 55(1suppl):55-60. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Gardner DG. The peripheral odontogenic fibroma: An attempt at clarification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982;54(1):40-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial pathology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1995:374-6. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Eversole LR, Leider AS, Nelson K. Ossifying fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of sixty four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 60:505-511 [Google Scholar] [Crossref].

- Eversole LR, Sabers WR, Rovin S. Fibrous dysplasia: A nosology problem in the diagnosis of fibro osseous lesion of the jaw. J Oral Pathol 1972;1:189-220. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Layfield LL, Shopper TP, Weir JC. A diagnostic survey of biopsied gingival lesions. J Dent Hyg 69:175-179. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JN, Kaugars GE, Abbey LM. Comparison between the peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheral odontogenic fibroma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989;47:378-82. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histopathologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 63(4):452-461. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Cuisia ZE, Brannon RB. Peripheral ossifying fibroma-a clinical evaluation of 134 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dent 2001;23(3):245-48. [Google Scholar]

- Poon CK, Kwan PC, Chao SY. Giant peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;53(6):695-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Mariano RC, Reis Oliveira M, Silva AD, et al. Large peripheral ossifying fibroma: clinical, histological, and immunohistochemistry aspects. A case report. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac 2017:39-43. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar SN, Jacoway JR. Peripheral fibroma and peripheral fibroma with calcification: Report of 376 cases. J Am Dent Assoc 1966;73(6):1312-20. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kumar SK, Ram S, Jorgensen M, et al. Muliticenter peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Oral Sci 2006;48:239-43. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Barot V, Chandran S, Vishnoi S. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: A case report. J Indian Soc Periodontol.2013; 17:819-22. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Eversole LR, Rovin S. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 1972;1(1):30-8. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Miller CS, Henry RG, Damm DD. Proliferative mass found in the gingiva. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1990;121(4):559-60. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Kendrick F, Waggoner WF. Managing a peripheral ossifying fibroma. ASDC J Dent Child 1996;l63(2):135-138. [Google Scholar]

- Moon WJ, Choi SY, Chung EC, et al. Peripheral ossifying fibroma in the oral cavity. CT and MRI findings. Dentomaxillofac Radio 2007; 36(3):180-2. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 63(4): 452-61. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Batsakis JG. Non-odontogenic tumors: clinical evaluation and pathology. Compr Manag Head Neck Tumors. 1999;1:1635-73. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Passos M, Azevedo R, Janini ME, Maia LD. Peripheral Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma in a child: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2007; 32: 579. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Marx RE, Stern D. Oral and maxillofacial pathology: a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Quintessence, Chicago 2003, 23-25. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Chen CM, Shen YS, Yang CF, et al. Artificial dermis graft on the mandible lacking periosteum after excision of an ossifying fibroma: a case report. Kaoh Siung J Med Sci 2007;23(7):361-5.[Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Marcos JAG, Marcos MJG, Rodriguez SA, et al. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: A clinical and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Oral Sci. 2010; 52:95-9. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Martins-Junior JC, Kiem FS, Kriebich MS. Peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla: case report. Intl Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018; 12: 295-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Hegde S, Ajila V. The varying clinical presentations of peripheral ossifying fibroma: a report of three cases. Rev Odonto Cienc. 2012; 27:351-5. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Farquhar T, Maclellan J, Dyment H, et al. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: a case report. Prat Clin. 2008; 74: 809-12. [Google Scholar]

- Walters JD, Will JK, Hatfield RT, et al. Excision and repair of the peripheral ossifying fibroma: a report of 3 cases. J Periodontol. 2010; 72: 939-44. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]