The effects of glycine, glutamate and their combination on cardiodynamics, coronary flow and oxidative stress in isolated rat hearts

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Macit Kalç?k

?skilip At?f Hoca State Hospital, Çorum

Turkey, Meydan Mah. Toprak Sok

No:7/8 ?skilip, Çorum/Turkey

Tel: 90-5364921789

Fax: 90-3645113187

E-mail: macitkalcik@yahoo.com

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact support@pulsus.com

[ft_below_content] =>Keywords

PR interval; QT interval; QT dispersion; Smoking cessation; Varenicline

Varenicline (Champix; Pfizer Inc, USA), which acts primarily as a partial agonist at the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) [1], is an effective choice for smoking cessation and is widely used. There are several studies in the literature reporting a good cardiovascular safety profile for varenicline; the drug has been well tolerated and has not been associated with increases in cardiovascular events and deaths, or with any significant effects on blood pressure and heart rate [2]. However, a recent systematic review [3] and several case reports [4] have raised concerns about the cardiovascular safety of varenicline. Moreover, a recent surveillance study has reported a total of 27 cases of arrhythmia, with unexplained cardiac death in two patients [5].

Cardiac arrhythmia can cause mortality. Sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block and ventricular tachycardia may also result in significant morbidity or mortality. The Framingham Heart Study [6] has demonstrated that even only first-degree atrioventricular block (PR interval >200 ms) is associated with a 1.44-fold risk for all-cause mortality and a 2.9-fold risk for pacemaker implantation. Prolonged QT interval and QT interval variability between the leads (QT dispersion [QTd]) are indicators of the heterogeneity of repolarization, which is known to be a predisposing factor for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death [7]. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), which provides information about the QT interval, is a representation of depolarization and repolarization of the ventricular myocytes. Thus, it is assumed that the increased QTd observed in cardiac diseases with heterogeneous ventricular recovery times reflects the disparity of ventricular recovery times [8,9]. The QTd is a simple, inexpensive and noninvasive method to measure underlying dispersion recovery of ventricular excitability. QTd is an electrophysiological factor and may predispose toward ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death [10].

In the current literature, the effects of varenicline on PR and QT intervals and QTd have not yet been studied. The aim of the present study was to determine the effects of varenicline on PR and QT intervals and QTd in the smoker population.

Methods

Study population and protocol

A total of 60 consecutive adult smokers who were admitted to the authors’ smoking cessation outpatient clinic were prospectively enrolled in the present study. All volunteers fulfilled all of the following inclusion criteria: no use of drugs that would potentially influence PR and QT intervals, and QTd; no history of ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, bundle branch block or abnormal serum electrolytes; normal resting ECG; and a good-quality ECG recording to measure the PR and QT intervals. The exclusion criteria were: moderate to severe valve diseases; congenital heart defects such as atrial septal defect; atrial fibrillation and other ECG abnormalities such as prolonged PR interval, bundle branch block and systolic left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <50% or left ventricular end diastolic dimension >5.5 mm); unreliable identification of the beginning of the P wave and end of the T wave in the ECG; and uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, renal dysfunction or coronary artery disease. Complete medical history, physical examination findings, blood chemistry profile (sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels), ECG and transthoracic echocardiography findings of all volunteers were recorded. The ECGs were numbered and presented to the analyzing investigator without name and date information. Approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained for the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Electrocardiographic data acquisition

A baseline 12-lead ECG was obtained for all volunteers following a 15 min resting period in a supine position, at 20 mm/mV amplitude and 50 mm/s sweep speed with standard lead positions using a commercially available machine (Cardioline Delta 60 Plus CP/I version; Remco Italy Cardioline, Italy) before varenicline therapy. Control ECGs were taken five days after the maximum drug dose (on the 15th day after the beginning of the treatment). Using a magnifying glass, PR intervals were manually measured by two cardiologists who had no information about the patients or one another. The PR interval was measured as the distance from the crest of the P wave to the crest of the QRS complex. The QT interval was measured from the onset of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. When U waves were present, the QT interval was measured to the nadir of the trough between the T and U waves. If the end of the T wave could not be identified, the lead was not included. Three consecutive QT intervals were measured with the aid of a magnifying glass and averages were calculated for each lead. Only ECG recordings with ≥8 different analyzable leads were accepted. The QTd was determined as the difference between the maximum and minimum values of QT interval duration in different leads [11]. The RR intervals were measured at surface ECG lead V1 for three consecutive cycles and the average value used. Where an interobserver difference of 10 ms in an RR interval or 20 ms in a PR, QT or Tp-e interval was found, the recordings, still coded, were reanalyzed and a consensus was reached if possible. The interobserver correlations of variation of these PR and QT intervals were <10%. ECGs were evaluated separately by two of the authors, and readings were compared when differences in interpretation were found. They were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous data are reported as mean (± SD) or median. Categorical variables are summarized as percentages. A paired t test was used to investigate the time-dependent variables. The relationship between durations-dispersions and parametric clinical variables were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis, and the Spearman correlation coefficient was used for nonparametric variables. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

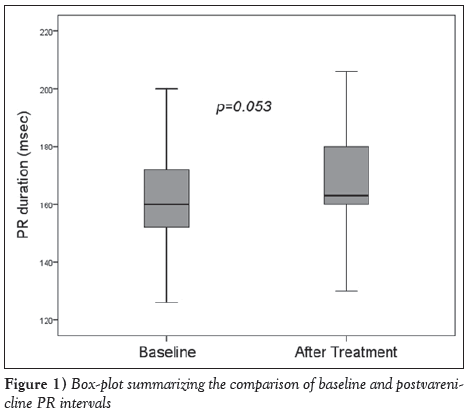

Results

The mean age of the volunteers was 38±10 years, and 34 (57%) were male. Fourteen (23%) had hypertension, eight (13%) had diabetes and six (10%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The mean heart rate was 74.7±13.3 beats/min, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures on admission were 122.3±14.3 mmHg and 76.5±10.2 mmHg, respectively (Table 1). Heart rate, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures did not change with varenicline treatment. The effects of varenicline treatment on ECG parameters were as follows: a limited prolongation in PR interval approached statistical significance (163.5±18.3 ms versus 168.2±17.9 ms; P=0.053) (Figure 1), while RR interval (796.3±117.4 ms versus 798.3±123.7 ms; P=0.926), QT interval (384.1±17.5 ms versus 383.4±20.9 ms; P=0.852) and QT dispersion (52.6±14.9 ms versus 52.2±14.9 ms; P=0.919) were unchanged (Table 2).

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 38±10 | |

| Male sex | 34 | (57) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.1±5.1 | |

| Hypertension | 14 | (23) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | (13) |

| Alcohol addiction/consumption | 0 | (0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 | (10) |

| Heart rate, beats/min, mean ± SD | 74.7±13.3 | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 122.3±14.3 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 76.5±10.2 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

Table 1: Demographic and clinical properties of volunteers (n=60)

| Variable | Baseline | After treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum QT interval, ms | 331.33±19.42 | 331.27±19.28 | 0.985 |

| Maximum QT interval, ms | 384.07±17.53 | 383.40±20.91 | 0.852 |

| QT dispersion, ms | 52.60±14.87 | 52.20±14.85 | 0.919 |

| Minimum PR interval, ms | 124.27±20.77 | 122.60±17.38 | 0.491 |

| Maximum PR interval, ms | 163.53±18.33 | 168.20±17.88 | 0.053 |

| RR interval, ms | 796.33±117.40 | 798.33±123.74 | 0.926 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 74.7±13.3 | 74.3±12.8 | 0.844 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 122.3±14.3 | 121.6±14.1 | 0.885 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.5±10.2 | 75.2±12.1 | 0.786 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. BP Blood pressure

Table 2: Electrocardiographic and clinical findings of volunteers at baseline and after varenicline therapy

There was no correlation between PR prolongation and age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD according to the correlation analysis (P>0.05 for all). Baseline PR interval was found to be weakly inversely correlated with PR prolongation (r=−0.381; P=0.038). Postvarenicline PR interval was strongly related to baseline PR interval (r=0.743; P<0.001), but weakly correlated with PR prolongation (r=0.353; P=0.045). No correlations were observed between postvarenicline PR interval and age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD (P>0.05 for all). Postvarenicline QT interval was modestly correlated with baseline QT interval (r=0.500; P=0.005) but was not correlated with age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD (P>0.05 for all), as well as postvarenicline QTd (P>0.05 for all).

Discussion

Although the use of varenicline caused a near-significant prolongation in PR interval in the present study, there were no effects on heart rate, QT interval and QT dispersion. Age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD had no effect on time interval changes with varenicline administration.

Cigarette smoking is a common risk factor for cardiovascular diseases [12-14]. Cardiovascular mortality has been shown to be reduced by 36% after cessation of smoking [15-17]. Despite all the smoking cessation initiatives in Western society, the frequency of cigarette use has been reported to be 20%. In recent years, Turkey has won plaudits for tobacco control [18]. With the recent launch of in-hospital smoking cessation initiatives for patients who had experienced a cardiovascular event, the cessation rates have been reported to have risen to 50% to 70% [19]. However, the cessation rate has been reported to be only 4% to 7% for smokers who attempt to quit smoking without help [20]. Therefore, medications that aid the cessation of smoking are important. There are three medical treatment options that have been shown to increase smoking cessation rates and have been approved for use: bupropion SR, varenicline and nicotine replacement [21]. Varenicline has been reported to be 1.77- and 2.66-fold more effective in long-term cessation of smoking than bupropion SR and placebo, respectively [22]. However, information regarding side-effect profiles, particularly on the cardiovascular safety of varenicline, is limited [2-5].

As mentioned, varenicline is a partial agonist of the α4β2 nAChR. nAChRs increase heart rate, myocardial contractility and blood pressure, resulting in increased myocardial work and coronary vasoconstriction that reduces myocardial blood supply [23]. It has been reported that varenicline affected the autonomous modulation by binding to this receptor and that the sympathomimetic cardiovascular effects of nicotine were mediated primarily by binding to α3β4 nAChR and α7 nAChR [24]. Moreover, varenicline increases dopamine release and reinforcement behaviours to a lesser extent than does nicotine, suggesting that it may have a lower abuse potential than nicotine [25]. However, the arrhythmogenic potential of varenicline has not been fully investigated. While single-dose varenicline has been reported to cause no change in heart rate variability in healthy smokers, it has increased the low frequency/high frequency ratio in healthy nonsmokers, which indicates increased sympathetic tonus [26]. The elimination half-life of varenicline is approximately 24 h [27] and the peak concentration is reached in 3 h to 4 h after oral administration. The recommended dosage is 1 mg twice daily following a one-week titration: 0.5 mg once daily on days 1 to 3, and 0.5 mg twice daily on days 4 to 7 [28]. In the present study, control ECGs were obtained five days after the maximum drug dose (on the 15th day after the beginning of treatment). While there was no change in heart rate and a limited increase in PR interval, it was clearly demonstrated that varenicline has no effect on QT interval and dispersion. Despite the autonomic system modulation by a nicotinic agonist may alter the homogeneity of ventricular repolarization [29], the lack of a significant change in QT interval and QTd after varenicline therapy was challenging in the present study.

Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers, which are used to treat hypertension, prolong the PR interval. Moreover, several clinical conditions, including prolonged QT syndrome, cardiac arrhythmia, ischemic cardiac diseases, pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, uremia, and electrolyte and acid/base disorders, and the drugs used in their treatment, including antihypertensives, antidiabetics, antipsychotics, antidepressants and opioid drugs, are known to influence the QT interval [30]. In our study, we excluded volunteers receiving such medications. The other variable that has a significant effect on QT is smoking. However, data regarding the effects of smoking on the QT interval and QT dispersion are conflicting. Although there are a number of studies reporting prolongation of the QT interval in smokers compared with nonsmokers [31-33], others have reported no significant differences [34], or even shorter QT intervals [35]. However, because the volunteers in our study were smoking both at the beginning of the study and when the control ECGs were taken, the possible positive and negative effects of smoking on the results of the present study can be ignored. Heart rate is another variable that can affect PR and QT intervals. Changes in heart rate play a major role in variation of PR and QT intervals. Increased heart rate leads to shortening of PR and QT intervals, whereas bradycardia results in PR and QT prolongation. Therefore, the QT interval corrected for heart rate is commonly calculated. However, we did not calculate the corrected QT interval in the present study because previous studies have shown that the rate correction of parameters of repolarization dispersion is likely unnecessary and may even distort the values and diminish the predictive usefulness of QTd [36,37]. In addition, due to the fact that there was no change in heart rate with the use of varenicline, the possible effects of heart rate on ECG were not observed.

Limitations

First, the present study was cross-sectional and did not evaluate the long-term effects of varenicline. In addition, the present study lacked ambulatory monitoring to investigate other factors such as heart rate variability. Second, patients who were at high risk for arrhythmia, including those with known heart failure, postmyocardial infarction, coronary artery disease or conduction abnormality, were excluded from the study to evaluate only the effect of varenicline on the heart. Thus, our results are not representative of this group of patients. Finally, the present study included a relatively small number of cases.

Conclusion

Smoking cessation is an important component of cardiac rehabilitation. Varenicline, which is used as a smoking cessation aid, may have a limited effect on atrioventricular conduction; however, it showed no effect on heart rate, as well as on QT interval and QTd, indicators of ventricular depolarization and repolarization that are more important parameters for arrhythmia. We can conclude that varenicline is also safe for adverse effects on electrocardiographic parameters despite a borderline significant prolongation in PR interval; however, to provide certain additional information regarding this issue, further large-scale studies are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mustafa Serdar Korkmaz MD, Chief of the Smoking Cessation Center, and Nurse Ayşe Eker for their devoted work on obtaining data through communication with volunteers.

Contributorship

All of the authors contributed to the planning, conduct and reporting of the work. All contributors are responsible for the overall content as guarantors.

Funding

None.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Faessel HM, Obach RS, Rollema H, Ravva P, Williams KE, Burstein AH. A review of the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of varenicline for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010;49:799-816.

- Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, Tonstad S. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: A randomized trial. Circulation 2010;121:221-9.

- Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2011;183:1359-66.

- Montastruc G, Degand B, Montastruc JL, Perault-Pochat MC. Cardiac arrest with varenicline: A case report. Therapie 2009;64:65-6.

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Maggo S, Tan M, Savage R, Ashton J. Cardiovascular events in patients taking varenicline: A case series from intensive postmarketing surveillance in New Zealand. Drug Saf 2012;35:33-43.

- Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, et al. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA 2009;301:2571-7.

- Zhang Y, Post WS, Dalal D, Blasco-Colmenares E, Tomaselli GF, Guallar E. QT-interval duration and mortality rate: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med 2011;19:1727-33.

- Sheehan J, Perry IJ, Reilly M, et al. QT dispersion, QT maximum and risk of cardiac death in the Caerphilly Heart Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2004;11:63-8.

- Benoit SR, Mendelsohn AB, Nourjah P, Staffa JA, Graham DJ. Risk factors for prolonged QTc among US adults: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005;12:363-8.

- Van de loo A, Arendts W, Hohnloser SH. Variability of QT dispersion measurements in the surface electrocardiogram in patients with acute myocardial infarction and in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:1113-8.

- Day CP, McComb JM, Campbell RW. QT dispersion: An indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br Heart J 1990;63:342-4.

- Yarlioglues M, Kaya MG, Ardic I, et al. Dose-dependent acute effects of passive smoking on left ventricular cardiac functions in healthy volunteers. J Investig Med 2012;60:517-22.

- Yarlioglues M, Ardic I, Dogdu O, et al. The acute effects of passive smoking on mean platelet volume in healthy volunteers. Angiology 2012;63:353-7.

- Dogan A, Yarlioglues M, Gul I, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in healthy volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:185-91.

- Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2003;290:86-97.

- Yarlioglues M, Kaya MG, Ardic I, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on blood pressure and heart rate in healthy females. Blood Press Monit 2010;15:251-6.

- Gül I, Karapinar H, Yarlioglues M, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on endothelial function. Angiology 2011;62:245-7.

- Devi S. Turkey wins plaudits for tobacco control. Lancet 2012;9830:1935.

- Smith PM, Burgess E. Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2009;180:1297-303.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1221-6.

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline 2008 Update. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Dept of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:56-63.

- Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2003;46:91-111.

- Di Angelantonio S, Matteoni C, Fabbretti E, Nistri A. Molecular biology and electrophysiology of neuronal nicotinic receptors of rat chromaffin cells. Eur J Neurosci 2003;17:2313-22.

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, et al. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 2007;52:985-94.

- Ari H, Celiloğlu N, Ari S, Coşar S, Doganay K, Bozat T. The effect of varenicline on heart rate variability in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. Auton Neurosci 2011;164:82-6.

- Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:12518-23.

- Chantix (varenicline) [prescribing information]. New York: Pfizer Inc; 2006.

- Browne KF, Zipes DP, Heger JJ, Prystowsky EN. Influence of the autonomic nervous system on the QT interval in man. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:1099-103.

- Malik M, Batchvarov VN. Measurement, interpretation and clinical potential of QT dispersion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;15;36:1749-66.

- Dilaveris P, Pantazis A, Gialafos E, Triposkiadis F, Gialafos J. The effects of cigarette smoking on the heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization. Am Heart J 2001;142:833-7.

- Ileri M, Yetkin E, Tandogan I, et al. Effect of habitual smoking on QT interval duration and dispersion. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:322-5.

- Singh K. Effect of smoking on QT interval, QT dispersion and rate pressure product. Indian Heart J 2004;56:140-2.

- Romero Mestre JC, Licea Puig M, Faget Cepero O, Perich Amador P, Márquez-Guillén A. Studies of cardiovascular autonomic function and duration of QTc interval in smokers. Rev Esp Cardiol 1996;49:259-63.

- Karjalainen J, Reunanen A, Ristola P, Viitasalo M. QT interval as a cardiac risk factor in a middle aged population. Heart 1997;77:543-8.

- Mark M, Camm AJ. Mystery of QT interval dispersion. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:785-7.

- Zabel M, Woosly RL, Franz MR. Is dispersion of ventricular repolarization rate dependent? PACE 1997;20:2405-11.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr Macit Kalç?k

?skilip At?f Hoca State Hospital, Çorum

Turkey, Meydan Mah. Toprak Sok

No:7/8 ?skilip, Çorum/Turkey

Tel: 90-5364921789

Fax: 90-3645113187

E-mail: macitkalcik@yahoo.com

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact support@pulsus.com

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the effects of glycine, glutamate and their combination on cardiac function, coronary flow and oxidative stress in isolated rat hearts, and to examine the effects of potential activation of N-methyl-Daspartate (NMDA) receptors in isolated rat hearts.

Methods: The hearts of male Wistar albino rats were excised and perfused according to the Langendorff technique, and cardiodynamic parameters (maximum rate of pressure development in the left ventricle [dp/dt max]; minimum rate of pressure development in the left ventricle [dp/dt min], systolic left ventricular pressure, diastolic left ventricular pressure, heart rate) and coronary flow were determined during the subsequent administration of glycine, glutamate and their combination. Oxidative stress biomarkers, including thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, nitrites (NO2 −), superoxide anion radical (O2 −) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), were each determined spectrophotometrically in coronary venous effluent.

Results: Treatment with glycine and glutamate alone did not cause a statistically significant change in any of the observed parameters; however, their combined administration induced significant decreases in dp/dt max, dp/dt min, heart rate and coronary flow compared with the control conditions. Treatment with glycine and glutamate together induced significant increases in NO2 −, O2 − and H2O2 levels. After the washout period, all parameters that had changed (cardiodynamic parameters, coronary flow and levels oxidative stress biomarkers) returned to values that were not significantly different from controls.

Conclusions: The results of the present study indicate that NMDA receptors likely have important roles in the function of the heart and coronary circulation. In addition, these results are suggestive of a damaging effect of NMDA receptor overstimulation in heart functioning, potentially mediated by oxidative stress.

-Keywords

PR interval; QT interval; QT dispersion; Smoking cessation; Varenicline

Varenicline (Champix; Pfizer Inc, USA), which acts primarily as a partial agonist at the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) [1], is an effective choice for smoking cessation and is widely used. There are several studies in the literature reporting a good cardiovascular safety profile for varenicline; the drug has been well tolerated and has not been associated with increases in cardiovascular events and deaths, or with any significant effects on blood pressure and heart rate [2]. However, a recent systematic review [3] and several case reports [4] have raised concerns about the cardiovascular safety of varenicline. Moreover, a recent surveillance study has reported a total of 27 cases of arrhythmia, with unexplained cardiac death in two patients [5].

Cardiac arrhythmia can cause mortality. Sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block and ventricular tachycardia may also result in significant morbidity or mortality. The Framingham Heart Study [6] has demonstrated that even only first-degree atrioventricular block (PR interval >200 ms) is associated with a 1.44-fold risk for all-cause mortality and a 2.9-fold risk for pacemaker implantation. Prolonged QT interval and QT interval variability between the leads (QT dispersion [QTd]) are indicators of the heterogeneity of repolarization, which is known to be a predisposing factor for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death [7]. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), which provides information about the QT interval, is a representation of depolarization and repolarization of the ventricular myocytes. Thus, it is assumed that the increased QTd observed in cardiac diseases with heterogeneous ventricular recovery times reflects the disparity of ventricular recovery times [8,9]. The QTd is a simple, inexpensive and noninvasive method to measure underlying dispersion recovery of ventricular excitability. QTd is an electrophysiological factor and may predispose toward ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death [10].

In the current literature, the effects of varenicline on PR and QT intervals and QTd have not yet been studied. The aim of the present study was to determine the effects of varenicline on PR and QT intervals and QTd in the smoker population.

Methods

Study population and protocol

A total of 60 consecutive adult smokers who were admitted to the authors’ smoking cessation outpatient clinic were prospectively enrolled in the present study. All volunteers fulfilled all of the following inclusion criteria: no use of drugs that would potentially influence PR and QT intervals, and QTd; no history of ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, bundle branch block or abnormal serum electrolytes; normal resting ECG; and a good-quality ECG recording to measure the PR and QT intervals. The exclusion criteria were: moderate to severe valve diseases; congenital heart defects such as atrial septal defect; atrial fibrillation and other ECG abnormalities such as prolonged PR interval, bundle branch block and systolic left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <50% or left ventricular end diastolic dimension >5.5 mm); unreliable identification of the beginning of the P wave and end of the T wave in the ECG; and uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, renal dysfunction or coronary artery disease. Complete medical history, physical examination findings, blood chemistry profile (sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels), ECG and transthoracic echocardiography findings of all volunteers were recorded. The ECGs were numbered and presented to the analyzing investigator without name and date information. Approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained for the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Electrocardiographic data acquisition

A baseline 12-lead ECG was obtained for all volunteers following a 15 min resting period in a supine position, at 20 mm/mV amplitude and 50 mm/s sweep speed with standard lead positions using a commercially available machine (Cardioline Delta 60 Plus CP/I version; Remco Italy Cardioline, Italy) before varenicline therapy. Control ECGs were taken five days after the maximum drug dose (on the 15th day after the beginning of the treatment). Using a magnifying glass, PR intervals were manually measured by two cardiologists who had no information about the patients or one another. The PR interval was measured as the distance from the crest of the P wave to the crest of the QRS complex. The QT interval was measured from the onset of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. When U waves were present, the QT interval was measured to the nadir of the trough between the T and U waves. If the end of the T wave could not be identified, the lead was not included. Three consecutive QT intervals were measured with the aid of a magnifying glass and averages were calculated for each lead. Only ECG recordings with ≥8 different analyzable leads were accepted. The QTd was determined as the difference between the maximum and minimum values of QT interval duration in different leads [11]. The RR intervals were measured at surface ECG lead V1 for three consecutive cycles and the average value used. Where an interobserver difference of 10 ms in an RR interval or 20 ms in a PR, QT or Tp-e interval was found, the recordings, still coded, were reanalyzed and a consensus was reached if possible. The interobserver correlations of variation of these PR and QT intervals were <10%. ECGs were evaluated separately by two of the authors, and readings were compared when differences in interpretation were found. They were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous data are reported as mean (± SD) or median. Categorical variables are summarized as percentages. A paired t test was used to investigate the time-dependent variables. The relationship between durations-dispersions and parametric clinical variables were assessed using Pearson correlation analysis, and the Spearman correlation coefficient was used for nonparametric variables. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

Results

The mean age of the volunteers was 38±10 years, and 34 (57%) were male. Fourteen (23%) had hypertension, eight (13%) had diabetes and six (10%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The mean heart rate was 74.7±13.3 beats/min, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures on admission were 122.3±14.3 mmHg and 76.5±10.2 mmHg, respectively (Table 1). Heart rate, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures did not change with varenicline treatment. The effects of varenicline treatment on ECG parameters were as follows: a limited prolongation in PR interval approached statistical significance (163.5±18.3 ms versus 168.2±17.9 ms; P=0.053) (Figure 1), while RR interval (796.3±117.4 ms versus 798.3±123.7 ms; P=0.926), QT interval (384.1±17.5 ms versus 383.4±20.9 ms; P=0.852) and QT dispersion (52.6±14.9 ms versus 52.2±14.9 ms; P=0.919) were unchanged (Table 2).

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 38±10 | |

| Male sex | 34 | (57) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.1±5.1 | |

| Hypertension | 14 | (23) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | (13) |

| Alcohol addiction/consumption | 0 | (0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 | (10) |

| Heart rate, beats/min, mean ± SD | 74.7±13.3 | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 122.3±14.3 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean ± SD | 76.5±10.2 | |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

Table 1: Demographic and clinical properties of volunteers (n=60)

| Variable | Baseline | After treatment | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum QT interval, ms | 331.33±19.42 | 331.27±19.28 | 0.985 |

| Maximum QT interval, ms | 384.07±17.53 | 383.40±20.91 | 0.852 |

| QT dispersion, ms | 52.60±14.87 | 52.20±14.85 | 0.919 |

| Minimum PR interval, ms | 124.27±20.77 | 122.60±17.38 | 0.491 |

| Maximum PR interval, ms | 163.53±18.33 | 168.20±17.88 | 0.053 |

| RR interval, ms | 796.33±117.40 | 798.33±123.74 | 0.926 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 74.7±13.3 | 74.3±12.8 | 0.844 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 122.3±14.3 | 121.6±14.1 | 0.885 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.5±10.2 | 75.2±12.1 | 0.786 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. BP Blood pressure

Table 2: Electrocardiographic and clinical findings of volunteers at baseline and after varenicline therapy

There was no correlation between PR prolongation and age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD according to the correlation analysis (P>0.05 for all). Baseline PR interval was found to be weakly inversely correlated with PR prolongation (r=−0.381; P=0.038). Postvarenicline PR interval was strongly related to baseline PR interval (r=0.743; P<0.001), but weakly correlated with PR prolongation (r=0.353; P=0.045). No correlations were observed between postvarenicline PR interval and age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD (P>0.05 for all). Postvarenicline QT interval was modestly correlated with baseline QT interval (r=0.500; P=0.005) but was not correlated with age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD (P>0.05 for all), as well as postvarenicline QTd (P>0.05 for all).

Discussion

Although the use of varenicline caused a near-significant prolongation in PR interval in the present study, there were no effects on heart rate, QT interval and QT dispersion. Age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and COPD had no effect on time interval changes with varenicline administration.

Cigarette smoking is a common risk factor for cardiovascular diseases [12-14]. Cardiovascular mortality has been shown to be reduced by 36% after cessation of smoking [15-17]. Despite all the smoking cessation initiatives in Western society, the frequency of cigarette use has been reported to be 20%. In recent years, Turkey has won plaudits for tobacco control [18]. With the recent launch of in-hospital smoking cessation initiatives for patients who had experienced a cardiovascular event, the cessation rates have been reported to have risen to 50% to 70% [19]. However, the cessation rate has been reported to be only 4% to 7% for smokers who attempt to quit smoking without help [20]. Therefore, medications that aid the cessation of smoking are important. There are three medical treatment options that have been shown to increase smoking cessation rates and have been approved for use: bupropion SR, varenicline and nicotine replacement [21]. Varenicline has been reported to be 1.77- and 2.66-fold more effective in long-term cessation of smoking than bupropion SR and placebo, respectively [22]. However, information regarding side-effect profiles, particularly on the cardiovascular safety of varenicline, is limited [2-5].

As mentioned, varenicline is a partial agonist of the α4β2 nAChR. nAChRs increase heart rate, myocardial contractility and blood pressure, resulting in increased myocardial work and coronary vasoconstriction that reduces myocardial blood supply [23]. It has been reported that varenicline affected the autonomous modulation by binding to this receptor and that the sympathomimetic cardiovascular effects of nicotine were mediated primarily by binding to α3β4 nAChR and α7 nAChR [24]. Moreover, varenicline increases dopamine release and reinforcement behaviours to a lesser extent than does nicotine, suggesting that it may have a lower abuse potential than nicotine [25]. However, the arrhythmogenic potential of varenicline has not been fully investigated. While single-dose varenicline has been reported to cause no change in heart rate variability in healthy smokers, it has increased the low frequency/high frequency ratio in healthy nonsmokers, which indicates increased sympathetic tonus [26]. The elimination half-life of varenicline is approximately 24 h [27] and the peak concentration is reached in 3 h to 4 h after oral administration. The recommended dosage is 1 mg twice daily following a one-week titration: 0.5 mg once daily on days 1 to 3, and 0.5 mg twice daily on days 4 to 7 [28]. In the present study, control ECGs were obtained five days after the maximum drug dose (on the 15th day after the beginning of treatment). While there was no change in heart rate and a limited increase in PR interval, it was clearly demonstrated that varenicline has no effect on QT interval and dispersion. Despite the autonomic system modulation by a nicotinic agonist may alter the homogeneity of ventricular repolarization [29], the lack of a significant change in QT interval and QTd after varenicline therapy was challenging in the present study.

Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers, which are used to treat hypertension, prolong the PR interval. Moreover, several clinical conditions, including prolonged QT syndrome, cardiac arrhythmia, ischemic cardiac diseases, pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, uremia, and electrolyte and acid/base disorders, and the drugs used in their treatment, including antihypertensives, antidiabetics, antipsychotics, antidepressants and opioid drugs, are known to influence the QT interval [30]. In our study, we excluded volunteers receiving such medications. The other variable that has a significant effect on QT is smoking. However, data regarding the effects of smoking on the QT interval and QT dispersion are conflicting. Although there are a number of studies reporting prolongation of the QT interval in smokers compared with nonsmokers [31-33], others have reported no significant differences [34], or even shorter QT intervals [35]. However, because the volunteers in our study were smoking both at the beginning of the study and when the control ECGs were taken, the possible positive and negative effects of smoking on the results of the present study can be ignored. Heart rate is another variable that can affect PR and QT intervals. Changes in heart rate play a major role in variation of PR and QT intervals. Increased heart rate leads to shortening of PR and QT intervals, whereas bradycardia results in PR and QT prolongation. Therefore, the QT interval corrected for heart rate is commonly calculated. However, we did not calculate the corrected QT interval in the present study because previous studies have shown that the rate correction of parameters of repolarization dispersion is likely unnecessary and may even distort the values and diminish the predictive usefulness of QTd [36,37]. In addition, due to the fact that there was no change in heart rate with the use of varenicline, the possible effects of heart rate on ECG were not observed.

Limitations

First, the present study was cross-sectional and did not evaluate the long-term effects of varenicline. In addition, the present study lacked ambulatory monitoring to investigate other factors such as heart rate variability. Second, patients who were at high risk for arrhythmia, including those with known heart failure, postmyocardial infarction, coronary artery disease or conduction abnormality, were excluded from the study to evaluate only the effect of varenicline on the heart. Thus, our results are not representative of this group of patients. Finally, the present study included a relatively small number of cases.

Conclusion

Smoking cessation is an important component of cardiac rehabilitation. Varenicline, which is used as a smoking cessation aid, may have a limited effect on atrioventricular conduction; however, it showed no effect on heart rate, as well as on QT interval and QTd, indicators of ventricular depolarization and repolarization that are more important parameters for arrhythmia. We can conclude that varenicline is also safe for adverse effects on electrocardiographic parameters despite a borderline significant prolongation in PR interval; however, to provide certain additional information regarding this issue, further large-scale studies are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mustafa Serdar Korkmaz MD, Chief of the Smoking Cessation Center, and Nurse Ayşe Eker for their devoted work on obtaining data through communication with volunteers.

Contributorship

All of the authors contributed to the planning, conduct and reporting of the work. All contributors are responsible for the overall content as guarantors.

Funding

None.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Faessel HM, Obach RS, Rollema H, Ravva P, Williams KE, Burstein AH. A review of the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of varenicline for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010;49:799-816.

- Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, Tonstad S. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: A randomized trial. Circulation 2010;121:221-9.

- Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2011;183:1359-66.

- Montastruc G, Degand B, Montastruc JL, Perault-Pochat MC. Cardiac arrest with varenicline: A case report. Therapie 2009;64:65-6.

- Harrison-Woolrych M, Maggo S, Tan M, Savage R, Ashton J. Cardiovascular events in patients taking varenicline: A case series from intensive postmarketing surveillance in New Zealand. Drug Saf 2012;35:33-43.

- Cheng S, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, et al. Long-term outcomes in individuals with prolonged PR interval or first-degree atrioventricular block. JAMA 2009;301:2571-7.

- Zhang Y, Post WS, Dalal D, Blasco-Colmenares E, Tomaselli GF, Guallar E. QT-interval duration and mortality rate: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med 2011;19:1727-33.

- Sheehan J, Perry IJ, Reilly M, et al. QT dispersion, QT maximum and risk of cardiac death in the Caerphilly Heart Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2004;11:63-8.

- Benoit SR, Mendelsohn AB, Nourjah P, Staffa JA, Graham DJ. Risk factors for prolonged QTc among US adults: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005;12:363-8.

- Van de loo A, Arendts W, Hohnloser SH. Variability of QT dispersion measurements in the surface electrocardiogram in patients with acute myocardial infarction and in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:1113-8.

- Day CP, McComb JM, Campbell RW. QT dispersion: An indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br Heart J 1990;63:342-4.

- Yarlioglues M, Kaya MG, Ardic I, et al. Dose-dependent acute effects of passive smoking on left ventricular cardiac functions in healthy volunteers. J Investig Med 2012;60:517-22.

- Yarlioglues M, Ardic I, Dogdu O, et al. The acute effects of passive smoking on mean platelet volume in healthy volunteers. Angiology 2012;63:353-7.

- Dogan A, Yarlioglues M, Gul I, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in healthy volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:185-91.

- Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2003;290:86-97.

- Yarlioglues M, Kaya MG, Ardic I, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on blood pressure and heart rate in healthy females. Blood Press Monit 2010;15:251-6.

- Gül I, Karapinar H, Yarlioglues M, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on endothelial function. Angiology 2011;62:245-7.

- Devi S. Turkey wins plaudits for tobacco control. Lancet 2012;9830:1935.

- Smith PM, Burgess E. Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2009;180:1297-303.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1221-6.

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline 2008 Update. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Dept of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:56-63.

- Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2003;46:91-111.

- Di Angelantonio S, Matteoni C, Fabbretti E, Nistri A. Molecular biology and electrophysiology of neuronal nicotinic receptors of rat chromaffin cells. Eur J Neurosci 2003;17:2313-22.

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, et al. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 2007;52:985-94.

- Ari H, Celiloğlu N, Ari S, Coşar S, Doganay K, Bozat T. The effect of varenicline on heart rate variability in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. Auton Neurosci 2011;164:82-6.

- Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:12518-23.

- Chantix (varenicline) [prescribing information]. New York: Pfizer Inc; 2006.

- Browne KF, Zipes DP, Heger JJ, Prystowsky EN. Influence of the autonomic nervous system on the QT interval in man. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:1099-103.

- Malik M, Batchvarov VN. Measurement, interpretation and clinical potential of QT dispersion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;15;36:1749-66.

- Dilaveris P, Pantazis A, Gialafos E, Triposkiadis F, Gialafos J. The effects of cigarette smoking on the heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization. Am Heart J 2001;142:833-7.

- Ileri M, Yetkin E, Tandogan I, et al. Effect of habitual smoking on QT interval duration and dispersion. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:322-5.

- Singh K. Effect of smoking on QT interval, QT dispersion and rate pressure product. Indian Heart J 2004;56:140-2.

- Romero Mestre JC, Licea Puig M, Faget Cepero O, Perich Amador P, Márquez-Guillén A. Studies of cardiovascular autonomic function and duration of QTc interval in smokers. Rev Esp Cardiol 1996;49:259-63.

- Karjalainen J, Reunanen A, Ristola P, Viitasalo M. QT interval as a cardiac risk factor in a middle aged population. Heart 1997;77:543-8.

- Mark M, Camm AJ. Mystery of QT interval dispersion. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:785-7.

- Zabel M, Woosly RL, Franz MR. Is dispersion of ventricular repolarization rate dependent? PACE 1997;20:2405-11.