The Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Biodiversity Conservation

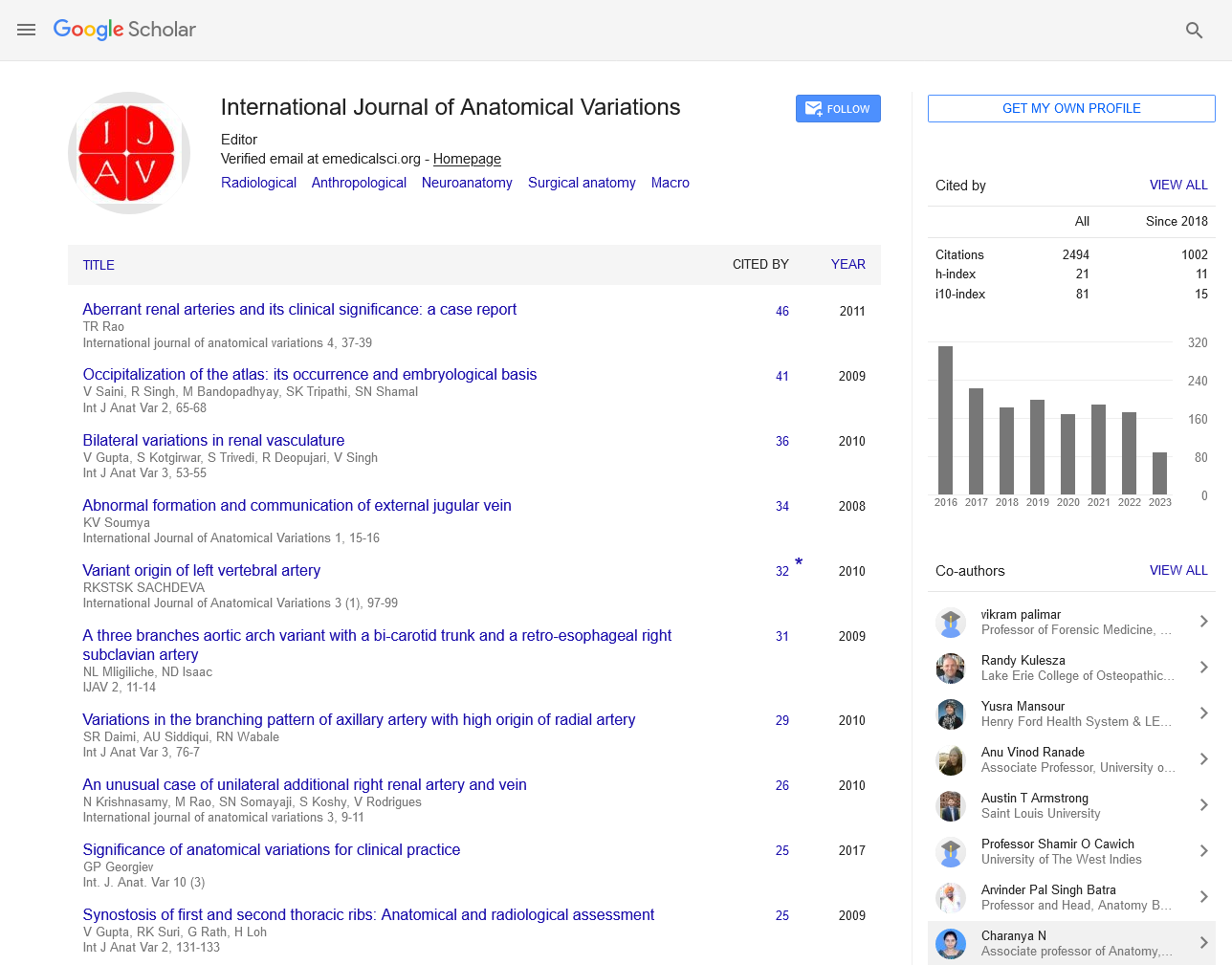

Received: 03-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. ijav-24-7259; Editor assigned: 05-Aug-2024, Pre QC No. ijav-24-7259 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-Aug-2024 QC No. ijav-24-7259; Revised: 24-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. ijav-24-7259; Published: 29-Aug-2024, DOI: 10.37532/1308-4038.17(8).423

Citation: Demontis Roberto. The Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Biodiversity Conservation. Int J Anat Var. 2024;17(8): 629-631.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Indigenous knowledge plays a crucial role in biodiversity conservation by offering unique perspectives and practices rooted in centuries of interaction with local ecosystems. This paper examines the intersection of indigenous knowledge systems and modern conservation strategies, highlighting the value of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in understanding species behavior, ecosystem dynamics, and sustainable resource management. Indigenous communities often possess an intricate understanding of their environments, which is reflected in their cultural practices, resource utilization, and land stewardship methods. This paper explores case studies that illustrate the successful integration of indigenous knowledge into contemporary conservation efforts, emphasizing the importance of collaboration between indigenous peoples and conservationists. By recognizing and respecting indigenous knowledge as a legitimate form of scientific understanding, we can enhance biodiversity conservation outcomes, promote cultural resilience, and foster a more inclusive approach to environmental management. The findings underscore the necessity of co-management strategies that honor indigenous rights and promote the intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge, ensuring the sustainability of both biodiversity and cultural heritage.

INTRODUCTION

Biodiversity , the variety of life on Earth, is crucial for maintaining ecosystem health and resilience. However, the rapid loss of biodiversity due to anthropogenic pressures such as habitat destruction, climate change, and pollution poses significant challenges to ecological balance and human well-being. As traditional conservation strategies struggle to keep pace with the complexity of these challenges, there is a growing recognition of the invaluable contributions of indigenous knowledge systems in biodiversity conservation [1].

Indigenous peoples have cultivated a deep understanding of their local environments over thousands of years, developing intricate relationships with the flora, fauna, and ecosystems surrounding them. This traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) encompasses a holistic view of nature, integrating cultural, spiritual, and practical dimensions that inform sustainable resource management practices. Indigenous knowledge is characterized by its adaptability, community-based nature, and intergenerational transmission, making it a potent complement to scientific approaches in conservation.

The incorporation of indigenous knowledge into biodiversity conservation strategies not only enhances ecological outcomes but also promotes social justice by recognizing the rights and voices of indigenous communities. It acknowledges their role as stewards of the land and the value of their lived experiences in understanding and managing local ecosystems [2,3]. As the global community increasingly seeks inclusive and equitable approaches to conservation, the collaboration between indigenous peoples and conservationists emerges as a pathway toward more effective biodiversity preservation.

This paper explores the multifaceted role of indigenous knowledge in biodiversity conservation, examining its significance, the challenges it faces, and the potential for synergistic approaches that honor both traditional practices and contemporary scientific methodologies. Through case studies and analysis, we aim to highlight the critical importance of integrating indigenous perspectives into conservation strategies, fostering a more holistic and inclusive framework for safeguarding our planet's biodiversity for future generations [4,5].

DISCUSSION

The integration of indigenous knowledge in biodiversity conservation has emerged as a transformative approach, fostering more effective and culturally resonant strategies for managing natural resources. Indigenous knowledge systems, often characterized by their holistic understanding of ecosystems, provide insights that are crucial for addressing contemporary environmental challenges. This discussion highlights the various dimensions of indigenous knowledge's role in biodiversity conservation, including its contributions to ecosystem management, community resilience, and the promotion of sustainable practices.

One of the primary advantages of indigenous knowledge is its deep-rooted understanding of local ecosystems. Indigenous communities have historically relied on their knowledge to navigate and adapt to environmental changes, leading to sustainable practices that promote biodiversity. For instance, traditional land management techniques, such as controlled burning and seasonal harvesting, have been shown to enhance habitat diversity and improve ecosystem health. By recognizing and implementing these practices [6], modern conservation initiatives can leverage the wealth of experience embedded in indigenous knowledge, resulting in strategies that are both ecologically sound and culturally appropriate.

Moreover, the collaborative management of resources can lead to greater community engagement and stewardship. When indigenous peoples are actively involved in conservation efforts, they are more likely to invest in the sustainable management of their environments. This participatory approach fosters a sense of ownership and accountability, encouraging communities to protect their natural resources and cultural heritage. Case studies, such as the co-management of marine protected areas in the Pacific, illustrate how indigenous knowledge can be instrumental in achieving conservation goals while empowering local communities [7].

Despite the promise of integrating indigenous knowledge into conservation practices, significant challenges remain. One primary concern is the historical marginalization of indigenous peoples and their knowledge systems. Colonial histories and ongoing systemic inequities have often led to the dismissal of indigenous voices in conservation discourse [8]. Recognizing the value of indigenous knowledge requires not only acknowledgment of its validity but also the dismantling of barriers that prevent indigenous communities from participating fully in decision-making processes. This necessitates a paradigm shift in conservation practices, moving away from top-down approaches toward inclusive, co-management frameworks that honor the rights and contributions of indigenous peoples [9].

Additionally, there is a need for capacity-building initiatives that support the intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge. As younger generations become more disconnected from their cultural heritage due to globalization and modernization, it is vital to create pathways for preserving and revitalizing indigenous practices. Educational programs that blend scientific and traditional ecological knowledge can empower indigenous youth and strengthen community resilience against environmental changes [10].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, indigenous knowledge serves as a vital resource in the quest for effective biodiversity conservation. It encapsulates centuries of ecological wisdom, shaped by intimate relationships between indigenous communities and their environments. By integrating traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) into modern conservation strategies, we can enhance our understanding of ecosystems and implement sustainable practices that respect both cultural heritage and ecological integrity.

The collaborative approach that emerges from recognizing the value of indigenous knowledge not only strengthens conservation efforts but also empowers indigenous communities, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility toward their natural resources. By dismantling the historical marginalization of indigenous voices and creating equitable frameworks for participation, we pave the way for more inclusive and effective conservation strategies.

As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, the lessons learned from indigenous practices offer invaluable insights into resilience, adaptation, and sustainable management. The urgent need for a paradigm shift in conservation approaches underscores the importance of valuing diverse knowledge systems and fostering partnerships between indigenous peoples and conservationists.

Ultimately, the path forward lies in a synergistic relationship that honors and integrates indigenous knowledge, promoting biodiversity conservation while safeguarding cultural identities. This holistic approach not only enriches our efforts to preserve the planet's biological diversity but also contributes to the creation of a more just and equitable world for all. Embracing indigenous knowledge is not merely an ethical imperative; it is essential for fostering a sustainable future that acknowledges the intricate connections between nature, culture, and community.

REFERENCES

- Osher M, Semaan D, Osher D. The uterine arteries, anatomic variation and the implications pertaining to uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25:S143.

- Park K-M, Yang S-S, Kim Y-W, Park KB, Park HS, et al. Clinical outcomes after internal iliac artery embolization prior to endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Surg Today 2014; 44:472-477.

- Patel SD, Perera A, Law N, Mandumula S. A novel approach to the management of a ruptured Type II endoleak following endovascular repair of an internal iliac artery aneurysm. Br J Radiol. 2011; 84(1008):e240-2.

- Szymczak M, Krupa P, Oszkinis G, Majchrzycki M. Gait pattern in patients with peripheral artery disease. BMC Geriatrics. 2018; 18:52.

- Rayt HS, Bown MJ, Lambert KV. Buttock claudication and erectile dysfunction after internal iliac artery embolization in patients prior to endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008; 31(4):728-34.

- Fontana F, Coppola A, Ferrario L. Internal Iliac Artery Embolization within EVAR Procedure: Safety, Feasibility, and Outcome. J Clin Med. 2022; 11(24):73-99.

- Bleich AT, Rahn DD, Wieslander CK, Wai CY, Roshanravan SM, et al. Posterior division of the internal iliac artery: Anatomic variations and clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 197:658.e651-658.e655.

- Chase J. Variation in the Branching Pattern of the Internal Iliac Artery. In: University of North Texas Health Science Center. Fort Worth. 2016: 1-33.

- Nayak SB, Shetty P, Surendran S, Shetty SD. Duplication of Inferior Gluteal Artery and Course of Superior Gluteal Artery Through the Lumbosacral Trunk. OJHAS. 2017; 16.

- Albulescu D, Constantin C, Constantin C. Uterine artery emerging variants - angiographic aspects. Current Health Sciences Journal 2014; 40:214-216.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref