Ways to avoid burnout among surgeons

Received: 15-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5575; Editor assigned: 16-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. PULJNRP-22-5575(PQ); Accepted Date: Jul 27, 2022; Reviewed: 21-Jul-2022 QC No. PULJNRP-22-5575(Q); Revised: 26-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. PULJNRP-22-5575(R); Published: 29-Jul-2022, DOI: DOI: 10.37532/ Puljnrp .22.6(7).118-119

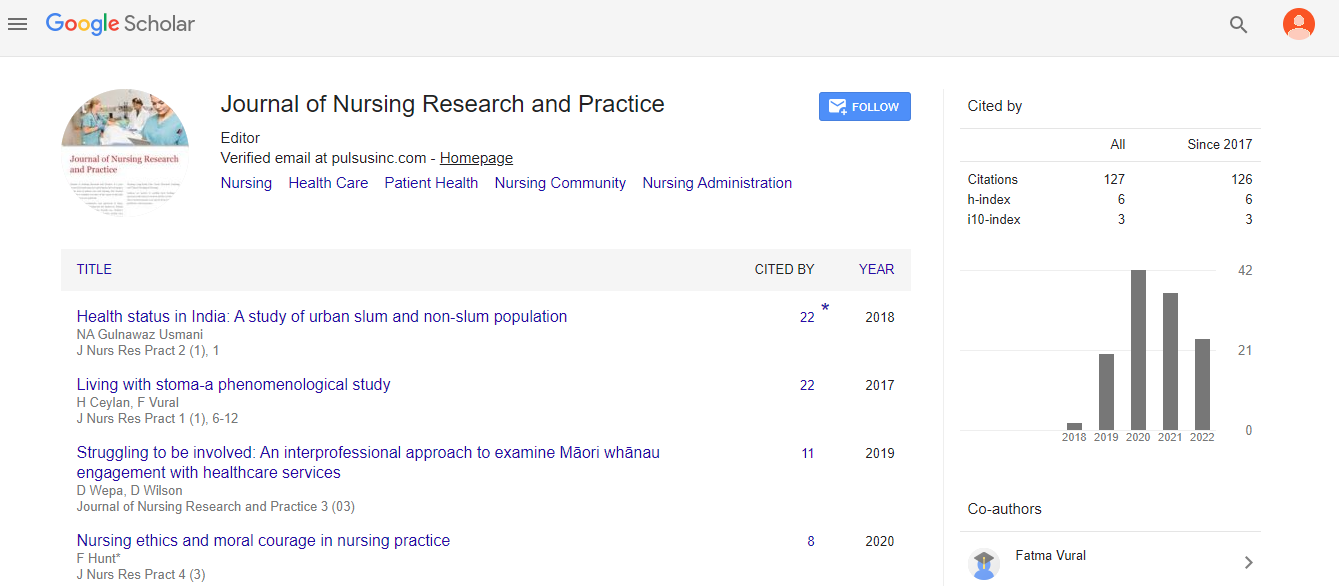

Citation: Michael J, Ways to avoid burnout among surgeons. J Nurs Res Pract. 2022; 6(7):118-119.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

In surgical practice, numerous sources of stress stressors are unpredictable; two examples of these unforeseen pressures in the surgical setting are the everyday workload and postoperative problems. They might contribute to the explanation of surgeon burnout, whose prevalence 34 to 53% has been the focus of numerous researches. However, despite the abundance of assessments, few recommendations for treatments have been made. This is particularly true given that by nature and training, surgeons are unlikely to be interested in burnout, which they are likely to view as something that only "others" suffer. In order to avoid surgeon burnout, techniques have been proposed in the literature. The goal of this attempt at clarification is to identify these strategies and evaluate the effects of this problem on the surgeon's professional and personal entourage as well. In addition to patient safety. There will be a description of prevention-based initiatives, many of which concentrate on modifiable stressors.

INTRODUCTION

There are numerous uncontrollable stressors in any type of surgical practice, including daily workload and postoperative complications [1]. These stressors can be found in "general" or specialized surgical practices, public or private practices, practices carried out by experienced surgeons or by young residents. The prevalence of surgeon burnout syndrome has been well studied; estimates range from 34 to 53% [2]. The definition offered by Maslach and Jackson [3], "a syndrome of emotional weariness, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment," is the most commonly referenced and largely accepted in the scientific literature. However, this theory has not yet been supported by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases (DSM). Nevertheless, the concept of burnout syndrome is now "unique [4, 5]." On the other hand, suggested remedies have been scarce, particularly insofar as surgeons are by nature and training averse to interest themselves in burnout, which they are prone to view as something experienced by "others" and they may tend to believe themselves to be more resilient than their non-surgical colleagues. In light of these factors, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of burnout and develop prevention strategies during the training years of future surgeons, particularly insofar as worry about its occurrence may prevent medical students from beginning or pursuing a career in surgery, contributing to a shortage of surgeons and increasing the workload of those who continue [6-10]. The purpose of this attempt at clarification was to locate in the pertinent literature the techniques proposed in order to prevent surgeon burnout and to evaluate the effects of this phenomenon on the patient's professional and personal entourage as well as on patient safety. We'll go over prevention-based measures from both a personal and an institutional perspective, many of which are centre on controllable stresses.

Identification and effects of burnout

Malash has identified the three main aspects of burnout. Emotional exhaustion is initially characterized by a loss of emotional resources, giving the surgeon the sensation that he has nothing more to offer his patients. The second factor, depersonalization, is linked to cynicism, disengagement from one's job, and an unfavorable, in some ways dehumanizing view of patients. The third dimension, on the other hand, is the propensity to appraise oneself [3].

BURNOUT PREVENTION

The problem of preventing burnout in a team, in a surgeon who has been exposed to or impacted by it, or in both is crucial. Both personal and institutional perspectives can be used to develop solutions [1, 2].

Conclusions

Preventing surgeon burnout is a significant task that requires both institutional and personal actions. The implementation of initiatives explicitly designed to enhance the well-being of surgeons is typically connected with favorable outcomes[10]. Reduced workload, maintaining work-life balance, creating a supportive environment with peers, cultivating personal relationships, seeking psychological help when you're feeling overwhelmed are some pretty straightforward solutions

References

- Sudan R, Seymour K. The impaired surgeon. Surgical Clinics. 2016 Feb 1; 96(1):89-93.

- Lu PW, et al. Gender differences in surgeon burnout and barriers to career satisfaction: a qualitative exploration. Journal of Surgical Research. 2020 Mar 1; 247:28-33.

- Salles A, et al. Social belonging as a predictor of surgical resident well-being and attrition. Journal of surgical education. 2019 Mar 1; 76(2):370-7.

- Shanafelt TD, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. InMayo clinic proceedings 2015 Dec 1 (Vol. 90, No. 12, pp. 1600-13). Elsevier

- Berman L, et al. Supporting recovery after adverse events: An essential component of surgeon well-being. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2021 May 1; 56(5):833-8.

- Yu TC, et al. Factors influencing intentions of female medical students to pursue a surgical career. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2012 Dec 1; 215(6):878-89.

- Berman L, et al. Supporting recovery after adverse events: An essential component of surgeon well-being. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2021 May 1;56(5):833-8.

- Allespach H, et al. Practice longer and stronger: maximizing the physical well-being of surgical residents with targeted ergonomics training. Journal of surgical education. 2020 Sep 1; 77(5):1024-7.

- Salles A, et al. Social belonging as a predictor of surgical resident well-being and attrition. Journal of surgical education. 2019 Mar 1; 76(2):370-7.

- Brandt ML. Sustaining a career in surgery. The American Journal of Surgery. 2017 Oct 1; 214(4):707-14.